Choices I made

I retell the story of Moses on the basis of themes that particularly affected the character of Zipporah, his Midianite-Kenite wife. This means that some favorite parts, such as the plagues of Egypt and the Ten Commandments, are not covered here. The focus is now mainly on the story of their love, the worship of YHWH, the melting of copper, the battle between the Israelites and the Midianites, and the ultimate fate of Moses' sons, Gershom and Eliezer.

My most significant interventions in the storyline of the Torah are as follows:

- I have omitted the symbolic ages of Moses and the forty years in the desert. The effect of this on the storyline is not significant: the stories in the Torah only cover the first two years and the last year of the exodus. The editor and writer who introduced the symbolic framework was aware of this; according to Deuteronomy 2:14, 38 years would have passed between Numbers 20:22 and 21:13.

- I present the priest of Midian and his daughter Zipporah as the ones from whom Moses learns to trust in YHWH and hears many of the stories of Abraham.

- I use the archaeological and anthropological insights in the Kenite-Midianite hypothesis concerning copper smelting and the fire of YHWH.

- I use the last chapters of the book of Judges to speculate about the relationship between Moses and his sons. In particular, the (probably original) reading in the Septuagint that there was a priest Jonathan in Dan who was the son of Gershom, the son of Moses.

The Jewish Publication Society Torah Commentary, the Midrash, Josephus, and Ross K. Nichols' lecture series "Honest to Moses" were used to interpret the Bible stories. Jacob Milgrom's JPS commentary on the Book of Numbers proved particularly invaluable. The rabbis in the Midrash show how Miriam and Aaron's conversation with Moses about his "Cushite wife" can be read as a reference to the problem of sexuality in the marriage of Moses and Zipporah (see introduction). https://www.thetorah.com/article/moses-and-the-kushite-woman-classic-interpretations-and-philos-allegory For more on this, see also: Naomi Koltun-Fromm (2010), “Zipporah’s Complaint: Moses Is Not Conscientious in the Deed! Exegetical Traditions of Moses’ Celibacy.”

Zipporah in the Thora

Zipporah, the eldest daughter of the priest of Midian and the wife of Moses, is mentioned by name only three times in the Bible. In Exodus 2, she marries Moses; in Exodus 4, she is traveling with him to Egypt; and in Exodus 18, her father brings her back to Moses in the Sinai Desert.

There is also the episode with Moses' "Cushite wife" in Numbers 12, that many readers take as a reference to a second wife of Moses, this time from black Africa. But there were also rabbis who read this as a story about the marital problems of Moses and Zipporah. This was their commentary on Numbers 12:1-3:

"And Miriam, with Aaron, spoke against Moses (12:1). From this we learn that Miriam spoke first. That was not her custom, but the subject required it."

"And Miriam, with Aaron, spoke against Moses (12:1). How did Miriam know that Moses had ended the marital relationship? When she saw that Zipporah no longer adorned herself as other married women did, she asked her why. "Your brother doesn't care," was the answer. That's how Miriam found out. She told Aaron, and they discussed it."

"And they said, 'Has YHWH spoken only to Moses?' (12:2). Did He not also speak to the patriarchs? And did they separate from their wives? 'Has He not also spoken to us?' (12:2). And we have not separated from our spouses!"

“And YHWH heard it (12:2). From this we learn that no one else was present, but that they spoke among themselves.”

Rabbi Nathan, however, says: "They also spoke in the presence of Moses, for it is written: And YHWH heard it. And the man Moses ... etc. (12:2-3) – but Moses suppressed it.

Sifre on Numbers: 99-100

from the school of Rabbi Ishmael (late 1st, early 2nd century)

From this perspective, Moses had just one wife, Zipporah, who may have come from Cushan, a Midianite region. This simplifies and deepens the story. Their marital problems create a story arch that needs resolution. It led me to speculate on a final episode of Moses and Zipporah on the day of his death.

The sons of Moses in the Bible

The sons of Zipporah and Moses are also barely mentioned in the Bible. It seems that later narrators found it difficult to accept that descendants of Moses were priests in a temple with idols in the territory of the tribe of Dan, while the Torah recognizes only a single central sanctuary and categorically rejects idols:

So the Danites came to Laish with the images that Micah had made and the priest who had served him. (...) They placed the silver idol there, and Jonathan, who was a son of Gershom, the son of Moses, became their priest.

Judges 18:27,30

Here and there we also hear about the Kenites, the family of Zipporah. They were part of the Midianite tribal confederacy. More and more biblical scholars are convinced that the Kenites already worshipped YHWH before the exodus of the Israelites. This is also indicated by the priestly role of Moses' father-in-law:

Moses' father-in-law Jethro brought a burnt offering and a peace offering to God, and Aaron and all the elders of Israel joined him in eating the sacrifice before God.

Exodus 18:12

Ages in the family history of Moses

The ages of Moses in the Torah are symbolic and go back to the scheme that Moses lived three lives of forty years each: prince of Egypt until his fortieth year, shepherd in Midian until his eightieth year, and finally leader and prophet of Israel until his death at the age of "120." This also made the people's stay in the desert forty years long. Of course, these numbers have an important symbolic meaning. But they are useless for the family history of Moses:

- According to the text, Moses is forty when he flees to Midian and marries the young Zipporah there. They have two sons, Gershom and Eliezer. On their way to Egypt, they are children (one of them even uncircumcised). In this family story, Moses would have spent only about fifteen years in Midian, not forty. He must then have been somewhere in his fifties.

- Aaron is older than Moses and may have been around sixty at the time of the exodus. He cannot have been much younger, as he already had four adult sons and a grandson, Phinehas.

- Miriam was even older than Aaron. She was already able to go out on her own when Moses was just born. As a young woman, she would in all likelihood have married much earlier than Aaron. This also fits with the early Jewish interpretation that she married Hur and had an adult grandson (Bezalel) who was responsible for the construction of the tabernacle. Her husband, Hur, is still alive when the Israelites enter the Promised Land. He founds the town of Bethlehem there.

The stories about Israel's time in the desert do not fill forty years either. A year and a half after the exodus, the people arrive at Kadesh-Barnea and make an unsuccessful raid into the Promised Land (Numbers 13 and 14). Other than that, not much happens before they leave again for the Promised Land; we only hear about a leadership conflict over the roles of priests and Levites. Deuteronomy 2:14 resolves this by having the Israelites spend another thirty-eight years wandering in the mountains of Seir between their departure from Kadesh-Barnea (Numbers 20:22) and their entry into the eastern part of the Promised Land (the crossing of the Zered in Numbers 21:12).

A shorter stay in the desert fits with the (probable) references to Gershom, the son of Moses, in Judges 17:7 and 18:30. In this story about the tribe of Dan, which takes place during the conquest of the land (Joshua 19:40-48), Gershom is the "young Levite."

In this story, I assume the following: Moses is around forty when he flees to Midian and in his fifties when he leads the people out of Egypt. His son Gershom is not much older than twelve at the time of the exodus and in his twenties at the time of the conquest. Miriam, Aaron, and Moses die in the desert, around the age of seventy. The older Hur is still there when Joshua leads the people into the Promised Land, where he founds the town of Bethlehem (1 Chronicles 4:4). He is then around eighty. Such lifespans of seventy and eighty years are also found in Psalm 90:10, the "prayer of Moses."

The Kenite-Midianite hypothesis and the religious significance of copper smelting

The Kenite-Midianite hypothesis posits that the worship of the God of Israel, YHWH, can be traced back to the Midianites, a confederation of tribes from the Bronze Age, and in particular to the Kenites, a tribe of copper smelters and metalworkers in the Sinai and Negev. The hypothesis is based on Egyptian hieroglyphs, pottery shards from the Negev, and poetic texts in the Hebrew Bible.

In “The Midianite-Kenite Hypothesis Revisited and the Origins of Judah” (2008), Joseph Blenkinsopp concludes: “[it] provides the best explanation currently available of the relevant literary and archaeological data.” For religious practice, see: Juan Manuel Tebes (2021), "The Archaeology of Cult of Ancient Israel's Southern Neighbors and the Midianite-Kenite Hypothesis." For Kenite habitation around Arad as a historical probability, see Nadav Na'aman (2016) “The ‘Kenite Hypothesis’ in the Light of the Excavations at Horvat ‛Uza.” For insight into the demography and economy (herders, traders, and copperworkers) of the Sinai and Negev, see: Mordechai Haiman (1996), “Early Bronze Age IV Settlement Pattern of the Negev and Sinai Deserts: View from Small Marginal Temporary Sites” and Juan Manuel Tebes (2020) Revolution in the Desert: A Reassessment of the Late Bronze/Early Iron Ages in Northwestern Arabia and the Southern Levant."

For the relationship between copper smelting and the worship of YHWH, see Nissim Amzallag (2018), “Who was the deity worshipped at the tent-sanctuary of Timna?” and “The Serpent as a Symbol of Primeval Yahwism” (2016). An anthropological study of the smelting process is provided by Rand Haaland (2004), “Iron smelting a vanishing tradition: ethnographic study of this craft in south-west Ethiopia.” For the archaeology of copper smelting, I have used Benno Rothenberg (1972), Timna: Valley of the Biblical Copper Mines and David Luria (2021), “Copper technology in the Arabah during the Iron Age and the role of the indigenous population in the industry.”

For the copper mines in Punon, see, among others, Erez Ben-Yosef, Thomas E. Levy, Thomas Higham, Mohammad Najjar & Lisa Tauxe (2010), “The beginning of Iron Age copper production in the southern Levant: new evidence from Khirbat al-Jariya, Faynan, Jordan.” For the analysis of skeletons: Marc A. Beherec, Thomas E. Levy, Ofir Tirosh, Mohammad Najjar, Kyle A. Knabb & Yigal Erel (2016), “Iron Age Nomads and their relation to copper smelting in Faynan (Jordan): Trace metal and Pb and Sr isotopic measurements from the Wadi Fidan cemetery.” For water pollution: J.P. Grattan, R.B. Adams, H. Friedman, D.D. Gilbertson, K.I. Haylock, C.O. Hunt & M. Kent (2016), “The first polluted river? Repeated copper contamination of fluvial sediments associated with Late Neolithic human activity in southern Jordan.”

For texts written by Zippora in an alphabet, I refer to inscriptions in Proto-Sinaitic script (a precursor to the Hebrew alphabet) that date from before the Exodus. The recent discovery of a lead "curse tablet" with a possible but difficult-to-decipher Proto-Hebrew inscription—if accepted—suggests that even the earliest Israelites already used it. See: Scott Stripling, Gershon Galil, Ivana Kumpova, Jaroslav Valach, Pieter Gert van der Veen, and Daniel Vavrik (2023), "You are Cursed by the God YHW:" an early Hebrew inscription from Mt. Ebal."

It was Josephus, the first-century Jewish historian, who wrote that the four letters of God's name are vowels (The Jewish War V.235). On the role of Asherah: William Dever (2005), Did God Have a Wife?: Archaeology and Folk Religion in Ancient Israel.

Numbers

In the case of Moses, there are only three generations between the patriarchs Levi and Judah and the people of the exodus, and in the case of the young Bezalel, only six generations. It is unlikely that in so few generations a group of twelve families, seventy migrants in total (Exodus 1:1-5), would have grown into a people of 601,730 able-bodied men (Numbers 26:51, elsewhere rounded to six hundred thousand), some two million people in total.

An exodus of two million Israelites would be a miracle from a historical perspective (which it is in the Torah), for which there are no clear traces to be found in archaeology. The population of the whole of Egypt in ancient times is estimated at around four million, and that of the Sinai/Negev at a few thousand, perhaps tens of thousands. There could not have been more, especially if they were dependent on livestock farming: in the Sinai, about five square kilometers of land per sheep or goat is needed to provide them with enough grazing. And an average Bedouin family has more than a hundred animals.

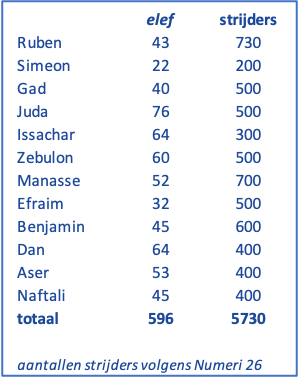

Most scholars see the large numbers as an exaggeration, fitting for the awe-inspiring story. A few point to the fact that the Hebrew word elef for thousand can also mean family or clan. If Dan had 64 elef 400 warriors (Numbers 26:43), instead of 64,100, you could also read: 64 families with a total of 400 warriors. That is why it has been suggested that Numbers 26 is based on a record of a total of 596 families with 5,730 warriors, which were later added up to 601,730 (596 thousand plus 5,730). The entire population would then have consisted of about twenty thousand people.

In terms of the lack of archaeological evidence, there is obviously a big difference between the current story of several million Israelites wandering through the desert for forty years and a group of twenty thousand people who did so for only a few years.

In any case, the idea of several hundred warriors per tribe fits with the story in Judges 18:11, where the army of the tribe of Dan consists of 600 warriors.

Numbers of clans and warriors in Numbers 26

Dating and historicity

The dating of slavery, the exodus, and the settlement in the land is difficult. To what extent are the stories based on historical events? And isn't the 400 years in Egypt, like the 40 years in the desert, a symbolic indication of a "long" period? Most scholars believe that Moses is a mythical figure. But many also believe that there is a historical core to the story of the Exodus, in which case the dating is important for the discussion of which elements could be historical. Consider the construction of the store cities of Ramses and Pithom, the presence of Semitic people in Egypt, the use of camels by desert peoples, the mining activities of the Egyptians in the Sinai, the presence of Philistines in Canaan, and the question of when cities such as Jericho and Arad were inhabited.

The oldest reference to Israel that archaeologists have found is an inscription by Pharaoh Menreptah (whose reign is dated from 1213 to 1203 BC): "(the tribe of) Israel is destroyed, its seed is no more." But to which phase of the story does this claim by the pharaoh refer: before, during, or after the Exodus and the settlement in the land? And have the children been exterminated, has the grain run out, or is the pharaoh boasting about a plundering expedition by his army?

The chronology of the biblical stories becomes clearer in the time of the kings, beginning with Saul, David, and Solomon (about three thousand years ago). When you consider how few generations there are between Abraham and the family of Moses and then to King David, a later date for the patriarchs and the Exodus would seem obvious. We have already seen that only a few generations are mentioned between the patriarchs and the Exodus: the progenitor Levi is the great-grandfather of Aaron. There are also not many generations between Aaron and the kings: his brother-in-law Nahshon, who leads the tribe of Judah, is the grandfather of Boaz, the husband of Ruth—who in turn is the great-grandfather of King David. All in all, there are good reasons to date the Exodus later than usual. See, for example, Gary Rendsburg (1992): "The Date of the Exodus and the Conquest/Settlement: The Case for the 1100s."

For a narrative reading of the Exodus, the dating and historical reality are less important. But it is precisely this narrative reading that highlights the fact that descendants of Moses and Zipporah were priests in the "alternative" temple of Dan (Judges 18:30). The priests of Jerusalem would not have invented such an 'uncomfortable' tradition themselves, and that is why the story of Zipporah and her sons is, for me, a strong indication that Moses actually lived.

Incidentally, there is a parallel to the pillar of smoke or fire from the tabernacle in Quintus Curtius' history of Alexander the Great V.2.7 (translation by John C. Rolfe, Loeb edition):

"When [Alexander] wished to move his camp, he used to give the signal with the trumpet, the sound of which was often not readily enough heard amid the noise made by the bustling soldiers; therefore he set up a pole on top of the general's tent, which could be clearly seen from all sides, and from this a lofty signal, visible to all alike, was watched for, fire by night, smoke in the daytime."

The origin of the Torah

The Torah came to us after several rounds of writing and editing over a long period of time. An example of this can be found in I Samuel 10:25, where Samuel lays down the laws concerning kingship, possibly a reference to Deuteronomy 17:14-20. Scholars distinguish between periods in which the name YHWH (LORD) was central and periods in which the name Elohim (God) was central. They see the whole of the Torah, Joshua, Judges, I and II Samuel, and I and II Kings, with the addition of the book of Deuteronomy (with a preference for "the LORD our God") as a later step. This also applies to the addition of the book of Leviticus by priests (who began to use the name YHWH less frequently).

There is no consensus on the exact order, demarcation, and dating of these periods. However, it is clear that in these editorial stages, the story grows and changes in certain directions. This can be seen in the following trends:

- Theology becomes more exclusive: Only YHWH is God, and He is God only for Israel.

- The earlier worship of the unrepresentable and unnameable YHWH by the Kenites and Midianites is replaced by a revelation of the name to Israel and frequent open use in the Torah (only later in history is the pronunciation of the name discouraged again).

- The emphasis shifts to a single sanctuary with only the descendants of Aaron as priests. The "Asherah" trees and the erected rough stones are banned as idols.

- The origin of the fire of YHWH disappears from view and is replaced by the image of God himself as a consuming fire (Deuteronomy 4:24).

- The miracles become greater in order to emphasize the omnipotence of YHWH and the unique position of Moses, Israel, and the Torah.

- The passage of time becomes symbolic (three times 40 years) and the numbers become enormous (600,000 men – not including women and children).

- The similarities with other descendants of Abraham are increasingly less recognized.

- All other peoples in the Promised Land must be exterminated to purify the land of idolatry; marriages with foreigners become problematic.

- The laws and orders of war come 'directly' from YHWH to Moses.

- The foreign Zipporah and her children with Moses disappear from the stories.

These editorial changes have not been implemented in every detail. Throughout the Torah, there are stories and fragments that bear witness to older layers. The current text is decisive for understanding the Torah as Jewish law, but for the family story of Moses, we sometimes have to dig a little deeper. That, by the way, is an editorial change and a retelling of the story on my part.

Historicity and scriptural authority

The free interpretation of the Torah in this book is intended to tell Zipporah's story, not to alter the text of the Torah. The Torah is what it is, with its large numbers, long lifespans, miraculous plagues, and holy wars. It is this text that Jews and Christians have been discussing for thousands of years.

Discussions about the origins of the Torah and the historical reality behind it do not detract from the authority that the Torah has for believing Jews and Christians. After all, that authority is about living in accordance with God's intention. In that case, a literal historical reading can even be dangerous. Take the Book of Joshua, for example. If you read it literally, it is a terrible story full of genocide and ethnic cleansing. Anyone who applies it literally may feel called upon to exterminate heretics and sinners.

The Church Father Augustine already pointed out that "love is the fulfillment of the law." He therefore believed that you should always interpret the Bible from the perspective of the commandment of love; if that is not immediately possible with a literal reading, then do it symbolically. As long as you allow yourself to be corrected by the love of and for God and your fellow human beings. In fact, that was already the intention of the writers and editors of the Torah and Joshua: they tell the story with an ever-increasing symbolic meaning and appeal to the devotion of their audience.

And then the biblical book of Joshua is also a story of perseverance, of faithfulness and devotion, and of a new order. You can also look at your own life in this way: are you willing to sanctify your whole life and devote it to God? Are you willing to form one people with others and seek unity in law and worship? Or, as Joshua says: "Choose this day whom you will serve (...). But as for me and my house, we will serve the Lord!" (Joshua 24:15, NIV).

Add comment

Comments