Smyrna, de tweede Eeuw

Small numbers have big effects. Imagine that around the year 40 there are a few thousand followers of Jesus, mainly in Jerusalem and Galilee, and that number grows by an average of 2 to 3% per year. Around the year 50, there were only a few groups of a few dozen followers in the Greek-speaking cities around the Mediterranean, less than a thousand people. But around the year 100, there were already about twenty thousand. And around the year 200, there were a few hundred thousand! These numbers fit well with what we see in our sources. After the Jewish War, which must have cost the lives of many Jewish followers of Jesus, the movement grew, particularly among non-Jews and through natural growth (i.e., many children and good mutual care). Of course, this is only a scenario, but it gives you an idea of how that Jewish sect from the first century, with its center of gravity in Jerusalem, could become a largely non-Jewish religion around the Mediterranean in the early second century.

It has been said that only 1% of people in ancient times were literate enough to write a story or an argument. That means that around the year 60, there could only have been a handful of experienced followers of Jesus who could do so in Greek. And we have now heard from many of them: Paul and Timothy, of course, a writer for James, another for Judas, then Mark and Silas for Peter, the writer of Matthew, Luke, and some of their collaborators. There cannot have been many more. You can imagine that the later movement cherished and copied their sparse writings. But by the year 100, when John of Patmos, John the Apostle, and the Elder leave us their work, there are already dozens who can write reasonably well; hundreds by the middle of the second century. The chances of their writings surviving were much smaller. There were simply too many of them and they were not authoritative enough. Papyrus decayed and writings that were not popular enough to be copied in time were forgotten, unless we happen to find their remains in a dry, dark cave in the desert or as quotations in more popular texts.

Travelers and writers around the beginning of the second century

In the beginning, Jesus' followers formed a movement of migrants and travelers. The numerous separate communities and the roads of the Roman Empire formed a physical internet of servers and connections through which ideas and writings were conceived, shared, and evaluated. We even see moderators emerging in the form of bishops who were tasked with combating the spread of fake news.

Between 90 and 110, we see these information flows reflected in a church handbook from Syria, in a pastoral letter from Rome to the Corinthians, and in the letters of a bishop from Antioch who has been sentenced to death and his host. The latter two meet in the city of Smyrna near Ephesus; the old man is on his way to Rome to be fed to the lions. They write letters to Ephesus, Magnesia, Tralles, Rome, Philadelphia, Smyrna, and Philippi. It seems that these letters were edited as a collection, just like the collection of Paul's letters. We see that these churches along the road from Syria to Rome were in frequent contact with each other. Ideas, notes, and copies of the "writings of the apostles" and collections thereof were thus disseminated. Scholars believe they recognize expressions and phrases from almost all the books and letters of the New Testament in these letters, with the exception of the letters of Jude, II Peter, II John, and III John. But it is not yet a fixed collection, let alone "sacred scripture." They reserve that term almost exclusively for the Hebrew Bible, which they quote in the Greek translation.

Yet another bishop from Hierapolis describes how he himself asks travelers about words of Jesus that they still remember or have heard from the apostles. He collects and comments on words of Jesus in a series of five books that have unfortunately been lost. For him, a living memory takes precedence over a written text. Jesus himself is "the Word," not the writings of his apostles. The New Testament does not yet exist, but you could say that the church is "pregnant" with the Word.

The Jewish wars in the second century

The war of the Jews scattered among the nations

In the year 113, Emperor Trajan invades Armenia; between 114 and 117, he attacks the vast Parthian Empire, which the Romans have never been able to conquer and where many Jews live. Immediately, the desire flares up among Jewish exiles in the east and west. Is this their chance to liberate the Holy Land from the Romans? When Trajan moves to the Persian Gulf, Jews on the Euphrates attack the Roman garrisons that Trajan had left behind in the cities. Rebels in Israel destroy his grain supply. A Messiah arises in the cities of Libya, named Lukuas Andreas. Roman temples and bathhouses are destroyed. The revolution spreads to Egypt and Cyprus, where Salamis is destroyed. Tens of thousands of Greeks and Romans are slaughtered, "hundreds of thousands," writes a Roman historian. Lukuas' rebel army marches on Alexandria and burns temples and Roman monuments.

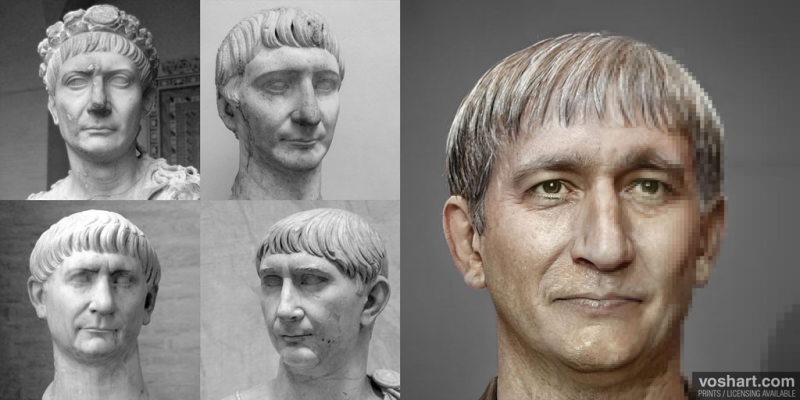

Trajan, emperor from 98 to 117, dies at the age of 63. Reconstruction: Daniel Voshart.

Then the tide turns. Trajan recaptures the cities between the Euphrates and the Tigris that had been taken by the Jews. A legion in Cyprus restores order and all Jews are forced to leave the island. For a year, fierce fighting rages in Egypt and Libya. The great synagogue of Alexandria lies in ruins and the Jews, including the Jewish followers of Jesus, are driven out of the city. Lukuas manages to escape to Lydda in Israel, but that city also falls and the last rebels are executed en masse.

The Jews have lost, but the Romans now see victory in Parthia slipping through their fingers. Trajan dies in the year 117, while trying to return to Rome, sick and weakened.

The Bar Kochba revolt

The misery for the Jews is not over yet. The new emperor, Hadrian, visits Jerusalem in the year 130 and decides to build a temple for Jupiter on the ruins of the Temple Mount. When construction begins, a new Messiah arises in Israel. They call him Simon bar Kochba, the "son of the star." The rebels mint coins with a star above the temple. Bar Kochba defeats the Romans and proclaims an independent Jewish state in 132. But the Romans strike back hard with an army of perhaps 100,000 soldiers.

In the year 135, the war is over and Judea is destroyed. It must be called genocide. Hundreds of thousands of people are killed, countless slaves and refugees. The Jewish followers of Jesus in Judea must also have suffered greatly. The rebels demanded that they recognize Simon Bar Kochba as the Messiah, and the Romans saw them as Jews who had to be killed or banished.

From now on, Jerusalem is a pagan city with a temple for Jupiter. Jews are no longer allowed to live there. The line of Jewish leaders of the Christian community in Jerusalem ends abruptly.

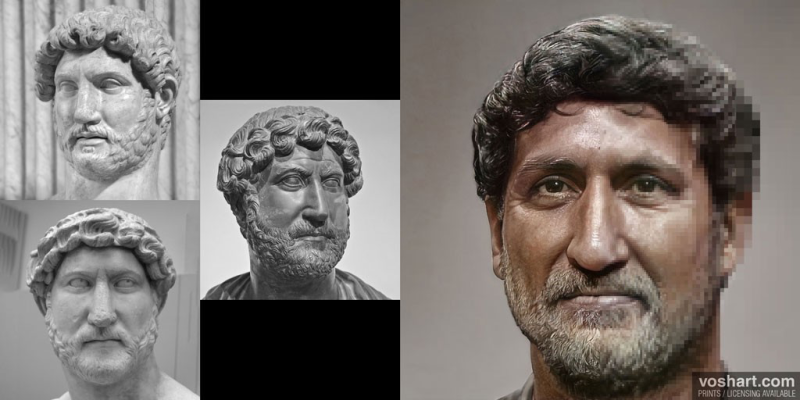

Hadrian, emperor from 117 to 138, died at the age of 62. Reconstruction: Daniel Voshart.

The rift is getting bigger

The church continues to grow, but opinions now vary widely. Some identify themselves as Jews or Jewish friends and want to remain active in the synagogue. It is said that some Jewish synagogues at that time included a curse against Christians in their regular prayers to keep this group out. Others gathered as Christians but observed Jewish holidays and days of rest, ritual cleansing, and marriage and dietary laws. Some of them saw Paul as their enemy.

Others said, "The Jews who rejected God's anointed one, Jesus, are no longer God's people; we are the new Israel." Or, "We are no longer Gentiles or Jews, but a new people, citizens of God's heavenly kingdom."

And some went even further.

Marcion

Around the year 130, a wealthy shipping magnate from the Black Sea arrives in Rome. He becomes a member of the church there and donates an enormous sum of money. After the third Jewish war, he embraced the doctrine that the warlike God of the Old Testament, the Hebrew Bible, was completely different from the heavenly Father preached by Jesus. He wanted the church in Rome to adopt this position. But they rejected him in astonishment. In the year 144, ties were severed and his donation was returned.

Marcion quickly organizes his own church, because there are many more who think like him. He founds congregations in the port cities around the Mediterranean, providing guidelines for leadership and rituals. More importantly, he determines what may be read in worship. He naturally rejects the Jewish Law and the Prophets: he wants to get rid of the Jewish God. But he also finds the works of the apostles substandard; only Paul has understood Jesus correctly. It is in the Epistle to the Galatians that Marcion reads how Paul dismisses the Law as the work of angels. But even the work of Paul and his companion Luke must be stripped of Jewish elements by Marcion. Marcion's holy scripture therefore consists of only two parts:

- The Evangelikon: a version of the Gospel according to Luke, stripped of Jewish elements and the physical resurrection.

- The Apostolikon: an edited collection of ten letters from Paul addressed to the seven churches, with the radical letter to the Galatians at the forefront. The conservative letters to Titus and Timothy are missing, while Philemon was understandably added to Colossians. The letter to the Ephesians is included under the name Laodiceans.

The secret behind the cosmos

There is a growing group of people who have had enough of both Roman imperialism and Jewish religious fanaticism. They translate this into their thinking about God and the gods and find support for this in Plato. This great philosopher distinguished between the highest God, who is purely immaterial, and the Creator. The former is the Father of All, the latter the Maker of this cosmos, including the gods who move across the sky as planets.

In the horror of the wars, more and more people begin to suspect that the Maker rules the cosmos as the emperor rules the Roman Empire. He seems to regard this world as his property and treats the children of the highest Father as his slaves. The gods of the Romans, the planets, are under him, as lesser gods who rule the cosmos and the peoples.

Is not the God of Genesis, they ask, that Maker, and are not the angels who serve him the idols of the cosmos? Yes, is not Yahweh himself called an angel—for example, in the story of Moses' calling at the burning bush? Did not Paul write to the Galatians about the Jewish Law that was given by angels? Those angels are nothing more than educators, in ancient times often slaves themselves, who must raise immature children. Every religion is thus essentially a form of angel worship. But Jesus revealed to us that we are children of the Father. And mature children, those who know who they are, stand above their educators.

Knowledge of that higher Father is called gnosis. The Father of All brought forth the Maker, who in his arrogance pretends to be the highest God. But during the creation process, particles of the Father became trapped in the cosmos, in the children of Adam and Eve. The Maker and his angels try to keep people in ignorance in order to serve them.

The divine Christ descended from the heavenly Father to free all divine particles from the cosmos. His revelation makes people discover that they are children of the highest Father. When they leave the body behind, they will ascend beyond the heaven of the angels and the Maker, until they arrive safely home with the Father. After that, this cosmos (heaven and earth) will perish.

One Gnostic says that Christ temporarily used the body of the man Jesus, another that he had a special body that was not made of flesh and did not need to eat or defecate, yet another that his body was an apparition. The core belief for all of them is that the created body does not matter: it is the prison in which the Maker has imprisoned our divine core.

These Gnostics teach us to read the Hebrew Bible, especially Genesis, with suspicion: what is behind this propaganda of the Creator? Some rewrite these stories to show what they believe really happened. That the Fall did not take place in paradise, but much earlier, in the ages of ages, when the Creator was brought forth and turned away from the Father.

Gnostic teachers such as Basilides in Alexandria (around 120), his pupil Valentinus in Rome (around 140), and his disciples around the Mediterranean, combine philosophy and Greek-Egyptian myths with an allegorical (symbolic) interpretation of the Gospels and the letters of the apostles. Others recorded this material in Gnostic revelations and gospels, often in the form of dialogues between apostles and angels or the spiritual Jesus, before or after the crucifixion.

Safe books

In contrast to Marcion's Bible and the many books written mainly by the Gnostics, many churches feel the need for a list of "safe" books. Which gospels and letters were actually written by or under the guidance of the apostles? And if you are not sure, which ones are accepted, preserved, and passed on as such by most churches, especially the oldest ones? What can we read in church and what not? The Prophets and the Apostles, someone writes. Another divides it further: the Law and the Prophets, the Gospel and the Apostles. In the Letter to Diognetus we read:

"The Word appeared to the disciples... The Eternal One whom we now call 'the Son,' through whom the church has been enriched. And Grace is multiplied as it unfolds in the saints, giving understanding, revealing mysteries, announcing the times, rejoicing over the faithful, and being given to those who seek it; to those who do not break their faith and do not transgress the limits of their fathers.

Then the fear of the Law is sung and the grace of the Prophets is made known,

the faith of the Gospel is established and the tradition of the Apostles is preserved,

and the Church leaps for joy."

The question of whether certain books are also "apostolic" and should have authority in the churches kept the debate going for a few more centuries. The short letters, Hebrews, Revelation, and a few other candidates, such as the Didache and I Clement, were debated for centuries. But on the core, they agreed: the four Gospels and the Acts, the letters of Paul, I Peter, and I John. And these books gradually gained more and more authority. By the end of the second century, they were already regularly quoted as sacred scripture.

Three collections

Jesus' followers made a surprisingly early transition from papyrus scrolls to bound books. Our oldest paper fragment comes from such a codex containing the Gospel of John, which was copied sometime in the second century, possibly as early as the first half of that century. A codex could hold the four most widely read gospels or the collected letters of Paul. This sends out a powerful message: there are multiple evangelists, but there is only one gospel of Jesus. Churches and teachers who draw far-reaching conclusions from, for example, the Gospel of John, are now invited to interpret the books in the light of each other. In the four-gospel collection, the content was fixed from the outset (although the order of Matthew, Mark, and Luke differs). Around the year 160, someone attempted to combine the four into a single story, but even that betrayed the standard: it was called the Diatessaron, a dish made from four ingredients.

The content of the collection of letters by Paul and his associates also varies: in the beginning, the personal pastoral letters were often not included, and in Egypt, the addition of Hebrews was popular. Theologians disagree on whether these collections were compiled and distributed before or after Marcion. Perhaps the pastoral letters became important as an argument against the radical interpretations of Marcion and his followers.

Towards the end of the second century, or perhaps only at the beginning of the third, a third collection was compiled and edited: the book of Acts of the Apostles with the seven general letters of James, I and II Peter, I, II, and III John, and Jude, sometimes supplemented with the book of Revelation. This supplements and corrects the story we read in the codex containing Paul's letters from a more legalistic perspective. Anyone who wants to hear the story of the young movement from both sides must also listen to these voices. This dynamic of liberation and order can be seen again and again: with II Thessalonians after I Thessalonians, with the messengers of James to the new churches, with the letters of instruction to Titus and Timothy, with the house rules in I Peter, Colossians, and Ephesians, with the writing of Luke and the Acts, and now with a third collection. It is the common thread in the telling and translating of the liberating message of the Jewish Jesus.

The birth of the written New Testament

The New Testament as a covenant between God and humankind goes back to the Way of Yeshua himself. Jesus experienced his relationship with God as an intimate relationship with his heavenly Father and passed that experience on to his friends. He saw his impending arrest and execution during the Jewish Passover in that light. It made him the Passover lamb of the covenant spoken of in Jeremiah 31:31-35:

The day will come, says the Lord, when I will make a new covenant with the people of Israel and the people of Judah, a covenant different from the one I made with their ancestors when I took them by the hand to lead them out of Egypt. They broke that covenant, even though they belonged to me, says the LORD. But this is the covenant I will make with Israel in the future, says the LORD: I will put my laws in their minds and write them on their hearts. I will be their God, and they will be my people. No longer will they teach their children to know the LORD, for they will all know me, from the least of them to the greatest, says the LORD. I will forgive their iniquity and remember their sin no more.

Jeremiah was not talking about a new contract on paper but about a covenant written in people's hearts. But after the death of the apostles, their writings, and those of their companions, became increasingly important. Which knowledge (gnosis) of God can be trusted? Gnostic teachers believe that the words of Genesis were misused to honor the creator and not the highest Father; they want to read the Gospels symbolically in order to unmask the God of the Jews. Gnostic gospels rewrite the words or deeds of Jesus to express their discoveries. Irenaeus, born around 125 in the same Smyrna with which we began this Epilogue, protests. The four apostolic gospels – no more and no less – form the canon, the standard of truth, he writes. He is now bishop of Lyon. Forty-eight people from his congregation there gave their lives for their Christian faith in the year 177. Irenaeus warns against the Gnostic teachers, who regard their martyrdom as a meaningless sacrifice to the false god of Israel. Irenaeus writes thick books to warn people against the errors of his opponents and their writings. The battle over the letter raged in full force.

Towards the end of the second century, a counter-movement emerges, the "new prophecy." These are followers of Jesus who rely primarily on the Holy Spirit speaking in the hearts of ordinary believers, just as they read in the Gospel of John and as John does in writing Revelation. A kind of Pentecostal movement.

The reactions are divided and emotional, torn between the desire for the Holy Spirit and the fear of false prophets. A learned leader in the Church of Rome would rather delete the Revelation and the Gospel according to John. Another church father, on the other hand, joins the new prophecy. Yet another writes a fierce argument against the movement. But he says he writes against his will, because he would rather not accidentally add anything to "the word of the gospel of the new covenant," that is, the written word of the New Testament. There, towards the end of the second century, you hear that term being used for the first time in connection with a particular group of writings. In defense, though.

Both positions (sacred scripture and the voice in the heart) will recur throughout church history. But so will the synthesis of the two: new prophecy and inner knowledge can be tested against the history of Israel and the story of Jesus. In this way, the connection with the God of Abraham and Sarah, Miriam and Moses, Mary and Jesus, Paul and James is preserved. This is what makes understanding the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament so important for storytellers and translators today. Do we experience the same Spirit that the Jewish Jesus passed on to his friends?

That is the canon (standard) of the written New Testament: not the end point but the benchmark of inspiration, inner knowledge, and revelation.

Summary: Epilogue

The letters and stories of Jesus' followers were copied, collected, and distributed from Antioch to Rome. During the second century, Paul's letters and the Gospels were compiled, followed later by the Acts and the other letters. Under pressure from two more Jewish wars and the influx of new members from other nations, some wanted to distance themselves from the Creator God of Israel. Others wanted to remain faithful to the Law. The growing and diverse movement produced more and more stories and visions, some of which were contradictory. But which ones inspire you? Ultimately, most churches recognized 27 letters, stories, and visions from fishermen, Pharisees, and refugees as the written record of the New Testament. Not as an end point, but as a benchmark for inspiration.

Smyrna, the city where the bishops Polycarp and Ignatius met and where Irenaeus was born. © Balage Balogh, Archaeology Illustrated.

A bit of background information: Books and letters outside the New Testament

For those who are interested, here is an overview of some important gospels and letters written by followers of Jesus up to the middle of the second century. You will recognize a movement that seeks to answer the questions and challenges of the second century based on the writings of the Jewish followers of Jesus. But you will also see a movement that is increasingly struggling with its Jewish roots.

A handbook and a songbook for churches

Towards the end of the first century, Jewish followers of Jesus in Syria compiled a short handbook for the scattered communities, which has the same atmosphere as the Gospel according to Matthew, to which it refers. They called it the Didache, the "teaching" of the apostles. It opens with ethics, the way of Jesus that leads to life, and warns against sin and eating sacrificial meat, as described in Acts 15. Then there are very practical instructions for baptism, the Lord's Prayer, and the Lord's Supper (celebrated as a Jewish meal instead of the annual Passover celebration).

Of interest to us is the unconditional hospitality that the congregations must offer every traveling Christian for several days, including traveling prophets, teachers, and apostles (messengers). But you must critically examine their words, and if they want to stay longer, they must work for a living. The churches are still led by several bishops (another word for elders) and deacons, just as in Phil. 1:1.

From the same region are the (probably Aramaic) Odes of Solomon: baptismal hymns of enchanting beauty. The anointed one sings that he opened himself to the Gentiles and was not defiled by his love for them, but rather made them his people. A cross between the psalms, the vocabulary of John, and the mysticism of love: "I would not have known how to love the Lord if He had not loved me constantly."

Bishops who wrote letters

At the end of the first century, one of the bishops of Rome wrote a long letter to the congregation in Corinth. The name is missing, but tradition calls it the First Letter of Clement. At that time, the terms bishop and elder were still interchangeable; the atmosphere was still Jewish and the letter was full of quotations from the Hebrew Bible, supplemented with a few words from Jesus. The writer compares the bishops to priests, the deacons to Levites, and the members of the congregation to the people of Israel. In order to maintain unity, communal meals must be led by the bishops, and love and humility must bind the brothers and sisters together. He points to the martyrdom of Peter and Paul as examples.

Important for our understanding of the development of the New Testament is that there are already numerous allusions to Paul's letters, including letters that many theologians now consider pseudonymous and the letter to the Hebrews. The author even explicitly assumes that the congregation has a copy of Paul's letter to the Corinthians at hand. He may also have been familiar with the Acts, James, and 1 Peter.

Under Emperor Trajan (the emperor to whom Governor Pliny sent questions about the persecution of Christians in Bithynia), the stubborn bishop of Antioch is sentenced to death in Syria. This Ignatius must – and wants – to die in Rome, where there was always a need for lion fodder around the holidays.

On his way, Ignatius writes letters to the churches in Asia, where he visits Polycarp in Smyrna and is visited by the bishop of Ephesus. In the meantime, a change in structure has been implemented in the churches of Syria and Asia Minor: there is now one bishop with his council of elders, the deacons, and the "widows." Most researchers consider the letters to Ephesus, Magnesia, Tralles, Rome, Philadelphia, and Smyrna to be authentic, as well as the letter to Polycarp himself and the letter that Polycarp sends to Philippi. The letters were frequently copied and circulated along the entire route from Antioch to Rome and back. Polycarp may be regarded as the editor and publisher of this collection of letters.

The letters continue to warn against the new teachings we already saw in John's letter to Ephesus. Ignatius emphasizes that Jesus is the Son of God and the son of Mary, that he was actually born in a physical body, crucified, and rose again. There is also a warning against followers of Jesus who want to follow Jewish laws too strictly: "It is better to learn 'Christianity' from a circumcised man than 'Judaism' from an uncircumcised man." There were people who still rejected Paul and believed that the followers of Jesus should observe the Jewish holidays and purity laws.

Ignatius explicitly mentions Peter and Paul as his great examples. He makes numerous references to various letters of Paul (including the letters to Ephesians and Colossians) and the Gospels: John and Matthew, and perhaps Luke. Polycarp is clearly someone who read a lot but also wrote extensively using the words of the evangelists and letter writers. In his only and short letter (about 2,200 words), he may have used about forty-eight expressions from Matthew, Mark, Luke, Acts, ten letters of Paul (including I and II Timothy), Hebrews, I Peter, and I and III John. It seems that the then nameless and undefined collection of books in Smyrna contained more or less the current New Testament. He even quotes Clement's letter.

Around this time, Bishop Papias of Hierapolis wrote a five-volume exposition of the words of the Lord, which unfortunately has been lost. From quotations, we know that he wrote about the oral tradition of the words of the Lord, about the Gospel according to Mark, and about the collection of sayings in Hebrew or Aramaic by Matthew. He seems to have known I Peter, Revelation, I John, and the Gospel according to John. Furthermore, he seems to have known a version of the story of Jesus and the adulterous woman, a story that was only later inserted into John 8.

Others also recorded memories of Jesus' words and deeds on paper, or edited earlier versions. Fragments of these have been found in ancient rubbish dumps in the Egyptian desert.

Distancing themselves from the Jews

The Gospel according to Peter must also have been written around the time of the Jewish wars, so called because Peter is presented as the narrator. As far as we can tell, it seems to be a short retelling of the crucifixion and resurrection. One could read into it that Jesus did not really suffer. But the most striking thing is that it is not Pilate who pronounces the judgment; the blame is placed entirely on Herod Antipas and the Jews.

In the run-up to the Bar-Kochba revolt, an anonymous writer warns against the disastrous desire to reconquer the land and rebuild the temple. He wants nothing to do with Christians who consider themselves part of the old covenant between God and the Jewish people. According to him, the Law of Moses, with its sacrifices and dietary laws, is not meant to be taken literally but symbolically. The Jews have failed to understand this, but according to the writer, Moses points forward to Christ and the church. The letter became popular and was circulated under the name: the Letter of Barnabas.

Revelations

Some people are completely fed up with Roman imperialism and Jewish messianic thinking. How much difference is there really between the two? And while we're at it, how different is the heavenly Father that Jesus revealed to us? Wasn't the spiritual Christ a messenger of another, divine reality? Wasn't that what he meant by the resurrection and the kingdom, that we would enter that other reality?

This spiritual, immaterial, and universal Father and the role of the Son of Man are elaborated in a treatise called Eugnostos. That material was then "cut up" early in the second century into a question-and-answer dialogue, the Wisdom of Jesus Christ, between the disciples and the risen Lord. The format is very reminiscent of the farewell discourse in the Gospel of John. Perhaps John's stories were indeed an inspiration. But the answers are not John's. They are formed from a mixture of philosophical, mythological, biblical, and astrological material with a sharp separation between spiritual and physical reality.

Another writing, the Letter of the Apostles, follows the same recipe, but now with material from the synoptic gospels, the Gospel of John, and the book of Acts. It is explicitly intended to answer the questions of the time in a more traditional way. Jesus is the son of God but also a man of flesh and blood. The Lord, or rather the writer, predicts that the Second Coming will take place "in 120 years," after successive wars. This would fit well with a dating of this work to a few years before 150.

Many such revelations follow, both Gnostic and non-Gnostic: to Peter, Paul, John, James (the brother of Jesus), Hermas, you name it. Pseudepigraphical texts have become commonplace. The revelation to James explicitly tells how this "hidden gnosis" of Jesus was passed on through James and others until the moment of publication: after the three devastating wars between Rome and the Jews.

Gnostic Christian gospels

The Gospel of Thomas will also have taken on the form in which we read it today during these decades: 114 sayings of Jesus, selected and edited to enable people to discover the kingdom and the Father within themselves. It is attributed to Thomas, who as the only disciple of Jesus is said to have heard these secret words. This could reflect the experience of the actual author as the interpreter of a minority voice in the early church.

These are the secret words that the living Jesus spoke and that Didymos Judas Thomas wrote down, (1) and he says, "Whoever finds the explanation of these words will not taste death."

(13) ... When Thomas returned to his companions, they asked him, "What did Jesus say to you?" Thomas answered them, "If I tell you even one of the words he said to me, you would pick up stones and throw them at me, and fire would come out of those stones to burn you."

(113) His disciples said to him, "When will the Kingdom come?" "It does not come by waiting for it. It is not a matter of 'it is here' or 'it is there.' On the contrary, the Kingdom of the Father is already spread out over the earth, but people do not see it."

The theme of one disciple receiving a special revelation is also found in the Gospel of Mary, a short account of Mary Magdalene's encounter with the risen Lord. Here too, the resurrection is not material, but the return of the soul to immaterial reality; upward and inward. To do so, she must escape the flesh, the passions, and the ignorance that try to hold her here. But Mary, and with her the author, brings this message to all the disciples, as the apostle to the apostles, despite Peter's initial protest.

Around the middle of the second century, many Gnostic Christians were no longer part of the movement but emphatically opposed to it. The Gospel of Judas is a sarcastic polemic against the church, placed in the mouth of a spiritual Jesus in the week before the crucifixion (which, incidentally, he does not need in order to ascend to the higher realm). It is a rewriting based on the synoptic gospels and the book of Acts. According to the author, all the apostles (and therefore also their later followers who celebrate the Last Supper as a sacrifice of Christ) have been misled; they are not followers of Jesus but of Judas! After all, Judas was the first to sacrifice the body of Jesus. Moreover, the priests sacrifice the misled believers, including the children, on the altar (baptism as a water grave), hoping for a physical resurrection. But that body, according to the author, is meaningless—other than to hold the soul captive to serve evil angels and false gods. The spiritual Jesus gladly leaves the body behind in this cosmos that is doomed to destruction.

Towards the end of the second century, the Gospel of Philip emerged, probably based on the notes of a teacher from the school of Valentinus. Twelve text units can be distinguished that correspond well with conversations with baptismal candidates: seven preceding the baptismal decision, three during the rituals, and two after. The book contains brilliant insights into the limitations of language and into both the oppressive and liberating effects of words, symbols, and rituals. This work also sees the apostolic Christians as slaves of the Hebrew God, but it also sees salvation in the words and rituals of Jesus that the apostles passed on. The apostolic gospels and letters therefore have authority, but the stories about Jesus must be interpreted allegorically and symbolically, according to this teacher. Mary, for example, represents women in all their roles: mother, sister, and partner. She symbolizes not only the Holy Spirit, the mother of humankind, and divine wisdom (Sophia), but also our soul, the bride of Christ. The kiss on the mouth represents the sharing of breath (spirit) and thus gnosis; with the same kiss on the mouth, the risen Lord greets his brother James in another writing from that time. The word for "partner" or "companion" refers not only to business or sexual communion but above all to spiritual communion.

32 There were three who always accompanied the Lord: Mary, his mother, and "her sister," and Magdalene, who is called his partner. For Mary is his sister, and she is his mother, and she is his partner.

33 "Father" and "Son" are single names. The "Holy Spirit" is a double name, for (spirits) are everywhere: they are above and they are below, they are in the hidden and in the visible (world). The Holy Spirit: he is in the visible (Son) – the one who is below, and in the hidden (Father) – the one who is above.

55 Sophia (in the sense of Lady Wisdom), who is called the "barren one," is the mother of the angels and the partner of the Savior. Mary Magdalene: the [Savior] loved her more than the (other) disciples. [When he saw her,] he greeted her several times (with kisses) on her [mouth]. The other [disciples were angry] with [her. Questioningly] they said to him, "Why do you love her more than all of us?" The Savior answered, saying to them, "Why don't I love you as I love her?"

Add comment

Comments