Israel and Syria, around the year 70

Introducing: Matthew

War literature

The majority of Bible scholars believe that Matthew was written in the 70s or 80s. They believe that the prediction of the destruction of Jerusalem did not come from Jesus himself, but was put into his mouth by his followers after the traumatic events of the year 70. First by Mark, and then by Matthew and Luke.

But not everyone agrees with this. The main reason why some believe that Mark and Matthew must have been written before the fall of Jerusalem follows from the prediction itself. Mark and Matthew follow the scenario that we also encountered in the Second Letter to the Thessalonians. The shadow of Caligula still hangs over the temple when Matthew repeats Mark's words almost unchanged. The writer expects that a gruesome idol or altar will be placed in the temple, after which a devastating battle will break out. After that, the Son of Man will return. In fact, Matthew tightens up the timetable in Mark: "Immediately after that," he writes (Matthew 24:29). You don't do that twenty years after the destruction of Jerusalem. No, the writer wants to urge his readers to take action. They have no time to lose, he thinks.

How differently Luke will write. He no longer expects an image or an altar. "But when you see Jerusalem surrounded by armies, know that its destruction is near" (21:20). And then, Luke has since realized, the Son of Man would not yet return. That is why he adapts the words of the prophecy in Mark and writes: "Jerusalem will be trampled by the Gentiles until the time of the Gentiles is fulfilled" (21:24). The same can be read in Revelation 11:2: “[The Gentiles] will trample on the holy city for 42 months,” a symbolic and God-determined period of time will pass before the Lord returns.

The simplest explanation for the differences between Matthew on the one hand and 2 Thessalonians and Mark on the other, and Luke and Revelation on the other, lies in the time of writing. The expectation in Luke and Revelation dates from after the destruction of Jerusalem, after the Lord had not returned. 2 Thessalonians and Mark were written just before the war and also before Matthew. In that case, Matthew, or at least this part of it, would have been written during the war or in the run-up to it, based on the conviction that at the height of the battle, immediately after the fall of Jerusalem, the Lord would also appear. And even if the Gospel as a whole was only completed later in Syria, it would still have been done in a community that had not long before been involved in a horrific war.

Try it: the Gospel according to Matthew as war literature.

The beginning of the war

When Paul arrives in Jerusalem in the late 50s, there are Sicarii (knife-wielding assassins) who commit murders during religious festivals to cause unrest. The high priest Jonathan is their first victim. A "prophet" from Egypt seduces "30,000" followers to march through the desert to the Mount of Olives. He wants to conquer Jerusalem, but the Roman procurator is ahead of him and they are defeated. Meanwhile, the followers of Jesus are also having a hard time. In the year 62, his brother James is stoned to death in Jerusalem. A few years later, Peter and Paul die in Rome, along with dozens of brothers and sisters. During those years, there are riots between Jews and Greeks in Caesarea, Alexandria, and Samaria, resulting in many deaths.

In the year 66, things come to a head when part of the taxes owed to Rome are not paid. The Roman procurator then takes the money from the sacred temple treasury himself, perhaps with a bonus for himself. The Jews are furious and a bloodbath ensues. While the elite try to restore peace, rebels capture the desert fortress of Masada. They slaughter the Roman soldiers and plunder the armoury. Their 'Messiah' is Menahem, the son of Judas the Galilean who rebelled against Quirinius' census. That year, a star is seen above the temple (possibly Halley's Comet). From Masada, they march on Jerusalem. The high priest is murdered and the Roman garrison is slaughtered. Then the violence escalates on both sides. In Caesarea, the Greeks and Syrians kill the Jewish minority, according to the Jewish historian Josephus, who likes to use large numbers:

"Within an hour, more than twenty thousand people lost their lives. (...) Groups of Jews looted the Syrian villages and towns in the vicinity. (...) Towns were reduced to ashes. (...) Numerous villages in the vicinity of all these towns were looted and ransacked, and countless inhabitants were captured and killed.

The Syrians, for their part, killed at least as many Jews; they too killed everyone they captured in the cities, not only out of hatred, as in the past, but also to forestall the danger that threatened them. A terrible chaos had descended upon all of Syria. Every city was divided into two camps, and each side believed that it could only survive by striking first. During the day, it was nothing but murder; at night, even worse, fear reigned. For although people thought they had got rid of the Jews, suspicion of their sympathizers remained everywhere. (...) In the cities, piles of corpses could be seen lying in the streets, old people next to small children and women who could no longer cover their shame. The terror throughout the province cannot be described in words. Even worse than the atrocities that were committed incessantly was the threat of the disasters that were yet to come. (...) Only in Antioch, Sidon, and Apamea were the Jewish inhabitants spared."

In this day and age, there are fierce debates between Jews and non-Jews, and also among Jews themselves. Can you imagine how this threatened to tear apart the mixed communities of Jewish and non-Jewish followers of Jesus in Syria? Even if they remained loyal to each other, their fellow countrymen would distrust them. Greeks and Syrians saw them as sympathizers of the Jews. Jewish people asked them to join their struggle.

Perhaps this is why Matthew came to understand more deeply the suffering of Jesus and the power of his message, precisely by allowing these two aspects to resonate together. And he wants to share this understanding as a source of comfort for the persecuted, as a guideline for the churches, as encouragement for missionaries among the nations, and above all as an inner compass: "love your enemies."

The Temple of Jerusalem, symbol of hope for the Jewish revolt.© Balage Balogh, Archaeology Illustrated.

Matthew

Matthew was a tax collector. Not for the Romans, but for Herod Antipas, although in practice that made little difference. He collected taxes from his little tax office, perhaps on the quay in Capernaum or on the trade route that ran from Egypt to Damascus. It was a good job, even if it didn't make him popular. But he could count and write.

Jesus saw him sitting there. "Come with me," he said.

Matthew prepared a meal with strange company: fishermen, hunters, and sinful women. Jesus was there.

"Why is he eating with tax collectors and sinners?" asked the pious.

"What does this verse in the Psalms mean?" he asked: "'I desire mercy, not sacrifice in the temple.'"

Around the beginning of the second century, Papias, the bishop of Hierapolis (the sister city of Laodicea and Colossae), wrote a book in five parts: Explanation of the Sayings of the Lord. Unfortunately, it has been lost. It was his passion to hear from John in Ephesus, from the daughters of Philip in Hierapolis, or from any passerby who had spoken with the apostles themselves.

"Matthew collected the sayings in Hebrew and grouped them into an orderly whole," he wrote, "and everyone after him translated and interpreted them to the best of their ability." Later, they thought that Matthew had written the first gospel in Hebrew (or Aramaic) and Greek, but that is not what Papias tells us. He only refers to an orderly collection of sayings in Hebrew (or Aramaic). These are not just striking one-liners, but also parables: short, somewhat absurd stories and images with which Jesus breaks down people's entrenched ideas about the kingdom of God.

You can see these sayings as favorite messages, anecdotes, and metaphors from the stump speeches of an American presidential candidate on the campaign trail. Everywhere the candidate tells the audience parts of his or her message. So does Jesus. Especially in a time without news media, repetition was the only way to spread your message with any consistency. This also includes the choice of twelve apostles whom Jesus sent out in pairs with his message. They were the disseminators of his ideas and thus prevented any major distortions. Oral teaching thus arose from the repetition of familiar elements but had no prior formulation or structure. It could be selected, varied, and expressed according to the circumstances.

The author of the Gospel

We have no idea who ultimately wrote the Gospel according to Matthew, but the difference with Mark lies mainly in the sayings that so inspired the writer. In that sense, it is nice to continue calling him or her "Matthew" for convenience. This Gospel is a beautiful composition of the collected sayings of Jesus, the Gospel according to Mark, fulfilled prophecies from the Hebrew Bible, and material of his own. Matthew groups many sayings into five "discourses": the Sermon on the Mount about the law, the discourse at the sending of the apostles, the parables of the kingdom, the discourse about the church, and the discourse about the end of Jerusalem. Especially with the composition of the Sermon on the Mount, with its unique view of justice, humility, activism, and surrender, Matthew continues to exert an enormous influence on the development of our thinking to this day.

A Jewish follower of Jesus

The vast majority of theologians believe that he was a Jewish follower of Jesus from bilingual Syria, for example Antioch. The author places great emphasis on the mission among all peoples, but is also positive about the law, at least as Jesus explains it:

"Amen, I say to you: until heaven and earth pass away, not one jot or tittle of the law will pass away, until everything has been accomplished.

Therefore, whoever breaks one of the least of these commandments and teaches others to do so, will be called least in the kingdom of heaven."

For Matthew, therefore, the law is also temporary, but not until the coming of the Messiah (as Paul taught) but for as long as we inhabit this earth. James would have agreed with him. That does not mean, however, that there is only the law. We live in two realities: the law in this reality and the eternal gospel. On earth, the church may "bind" and "loose" its members in relation to each other and their debts to God:

“Amen, I tell you: whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven.

“Heaven and earth will pass away, but my words will not pass away.”

“So every scribe who has been trained for the kingdom of heaven is like a householder who brings out of his treasure things both new and old.”

In the letters from Rome, we saw the understanding grow that Jesus is not only the coming Lord, but also the Lord through whom heaven and earth were created. He is eternal. He is not a son of God, but the Son of God. The Gospel according to Mark already posed the question: If the Messiah is only a descendant of King David, how can David address him in the Psalms as "My Lord"? The answer is now given in Matthew's nativity story: the virgin will conceive by the Holy Spirit. The child will be called Immanuel, "God with us." Matthew takes this from the ancient prophets. He does not explain what it means. And he says nothing about the role of Jesus or the Holy Spirit in creation. But he does say that creation will pass away and the words of Jesus will not. Matthew gives us a hint of who Jesus is: "God with us," forever.

An artist

Some people think that the twelve baskets refer to the bread for the twelve tribes of Israel and the seven baskets to the seven non-Jewish peoples in Israel. Bread for the children and bread for the dogs in their homes, a woman from Syria would conclude."Why retell a story?" Aristotle asks in his reflection on Greek tragedies. What effect does it have if your audience already knows the story? It is precisely then, Aristotle argues, that the poet can demonstrate his artistry through the way he presents the familiar facts. The author decides how to group and express the events and words, and what associations to make. The audience gets to see how these familiar elements are presented in a different light, producing new resonances and symphonies.

Matthew sees symbols and patterns and communicates with us by highlighting them. He does this right from the start with his choice of a genealogy in which Jesus is born into the line of succession of the kings of Israel, from Abraham to Jesus. He sees a pattern of 3 times 14 generations, with the reign of David and the Babylonian exile as turning points in the series. Anyone familiar with history can see that Matthew omits a few kings, and anyone who can count can see that the pattern is one that you have to want to see. But "six times seven ancestors" means that with Jesus a new era is dawning: the Sabbath for the people of God.

Another pattern he sees concerns the damaged women in his list: Tamar, who had to seduce her father-in-law in order to become pregnant, Rahab the prostitute from Jericho, the foreign widow Ruth who found her redeemer in Boaz, and the married woman with whom David fathered his son Solomon. This pattern is continued and reversed in the fifth woman, Mary: her early pregnancy is no argument for rejecting Jesus as David's heir because he was born of fornication or rape. Jesus' end proves his beginning. That is why she must be seen as the virgin of whom the prophet Isaiah spoke at the (biologically completely normal) birth of King Hezekiah, centuries earlier.

Matthew "extrapolates" prophecies from the Hebrew Bible to the story of Jesus. Followers of Jesus had been collecting such prophecies for some time, but Matthew now chooses which ones to use to present Jesus to the public. He is 'God with us' born of a virgin, the star of Jacob, God's promised anointed one (from David's hometown of Bethlehem), God's apple of the eye called out of Egypt, the new Moses who survived Pharaoh's infanticide and was dedicated to God as a 'Nazarene'. In effect, he is also saying that the land of Israel has become a land of dark misery and that a new exodus is needed. A new Moses and a new Joshua to save the people from their sins. Were there historical facts behind this, or is this Matthew's poetic license? It's a question you might ask a historian, but it sounds a bit strange to an artist. Compare it to the medieval painters who painted an ox and a donkey at the stable where Jesus was born. That was mainly a reference to Isaiah 1:3: "An ox knows its owner, and a donkey knows its master's crib, but Israel does not know; my people do not understand me." You don't ask the painter if he is sure there was an ox in the stable. Prophecies and symbols tell a bigger story to people who are open to them.

The same is true of the miracles that Matthew takes from Mark: he divides them into three groups of three stories and a total of ten miracles. For many, this evokes the ten miracles of Moses in Egypt. They often refer to the five speeches that would then represent the five books of Moses, or to the Sermon on the Mount (in Luke, Jesus speaks in the field), which evokes the memory of the giving of the law on Mount Sinai. Furthermore, he has a preference for pairs when he adapts Mark's text: two possessed men, two blind men, and two women at the tomb.

The two miraculous feedings in Matthew and Mark are a special case. Because the second feeding is missing in Luke and John, some wonder whether the second feeding was added later to Mark and whether Matthew deliberately used that version (or whether a later version of Mark took it from Matthew). In any case, after the first feeding, 12 baskets of bread remain, and after the second, 7 baskets. During the boat trip that follows, Jesus challenges the disciples to understand the symbolic meaning of this. But he does not explain it!

The Star of Bethlehem

Matthew begins with a fairy tale that ends in a nightmare:

It was when Jesus was born in Bethlehem in Judea, in the days of Herod the king. Behold, magi from the east arrived in Jerusalem, asking, "Where is the newborn king of the Jews, for we have seen his star rise and have come to worship him."

"That must be in the city of David, in Bethlehem, as the prophet writes."

But Herod becomes afraid: is this the end of his reign and his dynasty? He asks when the star appeared. And then he orders all the boys in Bethlehem under the age of two to be killed.

The story alludes to a prediction in the books of Moses: "A star will rise out of Jacob, and a scepter will be raised in Israel." But in Syria, another association was more obvious. When Quirinius was governor of Syria (the same governor mentioned by Luke in his Christmas story), he had coins minted with a star and a ram. Not to tell of a shining angel and shepherds, but to claim an important astronomical coincidence for Rome: the royal planet Jupiter, together with the messenger of the gods, Mercury, had appeared on the horizon in the constellation Aries (the symbol for Syria and in particular for the region of Damascus and Jerusalem). With this coin from the year 5/6, Quirinius proclaimed that Roman rule over Syria and Judea was willed by the gods and written in the stars.

Under Nero, the coin was minted again; here is one from 56/57. Flatterers say that Nero could become king of Jerusalem and ruler of the whole world.

Matthew links the star of Quirinius and Nero to the birth of Jesus and connects him to older stories about King Herod, who consulted astrologers and even killed his own sons for fear of betrayal. With the story of the infanticide, Matthew paints him as the Pharaoh who killed the firstborn sons of the Israelites in order to keep them under his thumb as slaves. Thus, in Matthew's Gospel, Jesus becomes the new Moses who will deliver his people. It is a powerful political statement: not Rome or Nero, but Jesus is the savior.

Images of coins from the T. Cartwright Collection found on beastcoins.com.

Five big speeches

The Gospel according to Matthew can be listened to in about 2.5 hours. That was probably too long for a gathering of Jesus' followers, and it is quite possible that the Gospel was read in sections. The text itself does not provide a compelling structure, other than the structure already provided by Mark. Many commentaries suggest a seven-part structure: an introduction, five narrative sections, each containing one of the five discourses, concluding with the dénouement at Easter.

But what is innovative about Matthew is precisely that the sayings of Jesus, which his followers often already knew by heart, take on new meaning when heard in the story of his life, and the story of Mark also takes on new layers of meaning through the collections of sayings that Matthew includes. Therefore, you might consider reading or listening to the book in five parts, with both stories and sayings in each part:

- Jesus as the new lawgiver in chapters 1-7, announced by the prophets and John the Baptist and ending with the Sermon on the Mount.

- Jesus as the bringer of the kingdom in chapters 8-12 with miraculous signs and opposition from family and fellow countrymen; in chapter 10, the sending out of the apostles as the heralds who will proclaim the kingdom.

- Jesus initiating his disciples into the mysteries of the kingdom in chapters 13-17, beginning with the discourse on the parables and ending with the transfiguration on the mountain with Moses and Elijah.

- Jesus preparing his followers for their time without him in chapters 18-23, beginning with a discourse on the church and ending with an unmasking of religious hypocrisy and hierarchy. He admonishes his followers: "You are not to be called 'Rabbi,' for you have one Teacher, and you are all brothers and sisters."

- Jesus preparing his disciples for suffering in chapters 24-28, beginning with his discourse on the end times (which, according to Matthew, had already begun) and concluding with the example of Jesus' own suffering and resurrection.

The great commission

During or shortly after that devastating war, in which Rome gathered soldiers from all nations to defeat Israel, Matthew decided to end his gospel with the Great Commission to all nations. Matthew also saw that the mission among the nations was part of God's plan. When the eleven remaining disciples met the risen Jesus in Galilee, Jesus came to them and said:

“All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you. And remember, I am with you always, to the end of the age.”

Summary: “Love your enemies,” late 60s.

In the year 66, the Jewish revolt broke out and Nero sent a huge army led by General Vespasian to crush the rebellion. Many Jewish followers of Jesus in Israel are filled with questions. Will Nero be the emperor who wants to be worshipped as a god in the temple? Will the Lord now return to defeat him? And what should they do themselves? Fight or flee?

- You could read the Gospel of Matthew as war literature. It rewrites the prophecy in Mark and adds that immediately after the siege of Jerusalem, the Lord will return. It is not Rome or Nero who has the last word, but Jesus. The author is a law-abiding Jew who presents Jesus as the new Moses, who will deliver the people from their sins. King Herod is like the Pharaoh of Egypt who had the newborn Jewish boys killed. The writer arranges the healings in Mark as the signs that Moses performed to show that God would deliver his people. And he edits Jesus' sayings into five discourses that are combined with the stories of Mark. It is said that Matthew, a disciple of Jesus, wrote down Jesus' sayings in Aramaic. Perhaps that is why this gospel was given his name. By bringing the sayings and the stories together, both take on greater meaning. The fundamentalists who want to take up arms against Rome hear Jesus' words in the Sermon on the Mount as a new law: "Love your enemies." It is precisely in view of the Second Coming that we must walk the Way of the Lord.

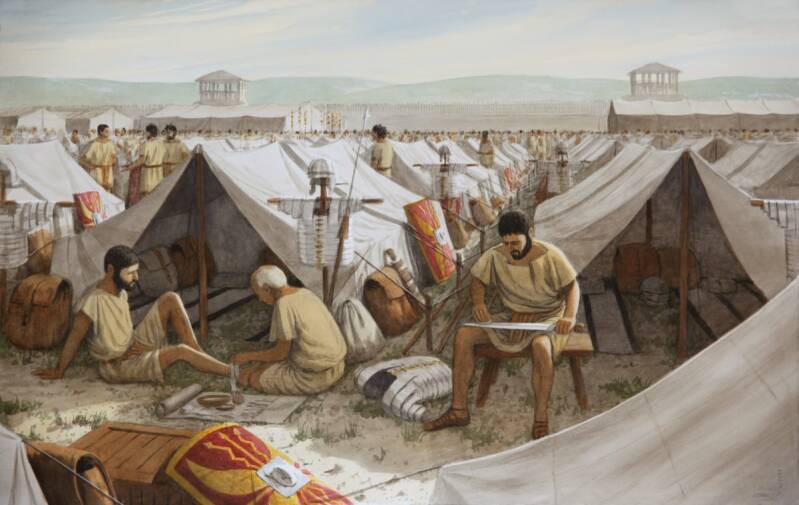

Roman army camp.© Balage Balogh, Archaeology Illustrated.

A bit of background information: Four Jewish movements

In his accounts of the Jewish War and Jewish history, Josephus describes the main Jewish sects. In summary, he says the following about them:

Pharisees

The Pharisees live piously and wisely. They are friendly toward one another and live in harmony with the rest of society. They respect their ancestors and oral traditions and interpret the laws accurately. The people therefore follow them in their regulations for holidays, sacrifices, and prayers. History is determined by Providence, they say, without this negating free will. After all, God created people with their own minds and temperaments. The souls of people continue to exist after death and will then be punished or rewarded. The souls of the righteous will participate in the bodily resurrection.

Sadducees

The Sadducees, who include the high priests and many of the leading citizens, deny the role of Providence. God is separate from evil in this world. Every human being must choose between good and evil of their own free will. In this regard, the Sadducees limit themselves to the five books of the Torah and like to dispute their interpretation. They also do not believe in the survival of the soul or punishment and reward in the hereafter. God's Spirit, our breath of life, returns to him who gave it. Their teachings are not shared by the people, so they have to follow the Pharisees' interpretation when they hold office.

Essenes

The Essenes, he writes, are particularly friendly towards each other. They do not participate in the sacrificial service in the temple but withdraw into monastic communities where they celebrate their own rituals, copy texts, and grow their own food. Many of them refrain from marriage, although they often adopt other people's children. They live in a community of goods and can stay with any sister community when travelling. They believe in the survival of the soul and that God will reward the righteous in the hereafter. They live extremely pious, austere and disciplined lives. They will never lie or swear an oath. They have a great knowledge of the scriptures and pay attention to the health of mind and body.

Sicarii

The Sicarii, the group that Josephus blames for the war, came out of the rebellion of Judas the Galilean during the census of Quirinius. These "knife-wielders" agree with the Pharisees' interpretation of the law but are unbreakably committed to freedom. They say that God is their only judge and lord. They are not afraid of death and do not care about the death of family or friends. They will never recognize the authority of the Romans out of fear or pain.

Add comment

Comments