Corinth and Rome, mid-50s

Introducing: Romans

In the mid-50s, Paul returned to Corinth, the Roman colony in Greece, located on the isthmus between northern and southern Greece and the hub of shipping routes to Italy and the East. There he wrote the Epistle to the Romans, perhaps the most influential text in the later Catholic and Protestant churches. But it is also the most controversial letter: some see it as the core of God's grace, others as the origin of homophobia and a morbid fascination with original sin and predestination.

But what did this letter mean to Paul and his friends?

Start reading from the back

There is no dispute that Paul wrote the letter. However, the last two chapters containing the travel plans and greetings are missing from quite a few manuscripts. Some theologians therefore have doubts as to whether those chapters, or only chapter 16, belong to the original letter. Others, and I suspect the majority, believe that it is easier to explain why someone would omit the greetings and possibly also the travel plans than why someone would have an interest in creating them and why others would have accepted them. It has also been suggested that chapter 16 was added by Paul when he sent a set of letters (the letters to Galatia, Corinth, and Rome) to Rome shortly thereafter to record his side of the conflict with Peter and James.

Travel plans

In any case, the travel plans and greetings provide the context in which the letter is to be read. Anyone who skips them runs the risk of drawing conclusions that Paul or the editor never intended. It is precisely these last chapters that bring us back to a concrete time and context in which Paul could have written.

I therefore suggest starting at 15:14. Paul wants Jesus' followers in Rome to contribute to the nations discovering God's salvation in Jesus. That has been his great mission on his travels from Jerusalem to Illyria, on the Adriatic Sea. And he would like to go even further: via Rome to Spain, the end of the known world.

But now Paul must first go to Jerusalem to hand over the proceeds of the collection among the churches in Macedonia and Greece to James and the other leaders in Jerusalem. In doing so, he fulfills a promise he made to James in his letters to the Galatians and the Corinthians: to help the poor. He wants to show in Jerusalem how important the work among the nations is and how the promises in the prophetic books are being fulfilled.

Greetings

Chapter 16 contains greetings to Paul's acquaintances in Rome and many in Corinth. Notable in the list of greetings are the Latin names in Corinth: Paul's co-worker Lucius – a Latin version of the name Luke, Gaius their host, Tertius the writer of the letter, and Quartus, as well as the many Greek names in Rome. Among the many Greek names, Paul's "relatives" are mentioned specifically: Jason and Sosipater, Herodion, Andronicus, and Junia. He even calls the last two respected apostles of Jesus, rather than Paul himself. Some translators translate this as "fellow countrymen," as if it were worth mentioning that there were a few Jews in the church in Rome. But I assume that Paul really means relatives, such as cousins or fellow tribesmen—Paul writes that he is from the tribe of Benjamin. After all, there were many more Jews whom Paul does not mention, such as Priscilla and Aquila, perhaps Mary, Rufus and his mother, and Timothy. If five relatives are greeted, for example from the tribe of Benjamin, how many Israelites would be greeted in total? Should we not assume that the church in Rome, formed among Jews some ten years earlier, still had a Jewish character?

A large number of Jewish church members fits the picture we have already seen: there were many Jewish migrants who regularly met each other in the port cities of the Greco-Roman world. A good example is Priscilla and Aquila: a couple from Pontus on the Black Sea who were among the followers of Jesus from Rome who moved to Corinth just as Paul arrived there in the late 40s. When Paul returned to Jerusalem and Antioch, they founded a church in Ephesus, from where they greeted the Corinthians in 1 Corinthians 16:19. They now live in Rome again and are greeted from Corinth in Romans 16:3. In Ephesus, they "risked their lives for me," writes Paul. Perhaps that is why they had to leave the city. Perhaps they and many other Corinthian friends were able to return to Rome after the death of Claudius in 54. Various sources report that it was Claudius who expelled a group of Jews from Italy because of trouble over a certain "Chrestus." Such an expulsion could end with the death of the emperor.

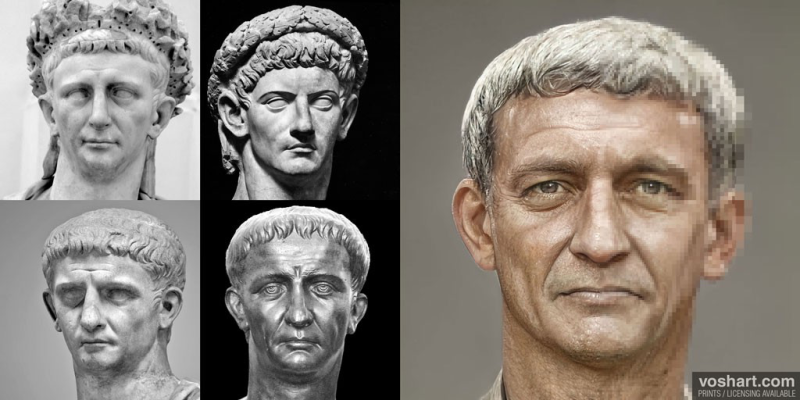

Claudius, emperor from 41 to 54, possibly poisoned at the age of 63. Daniel Voshart

Performance Art

This clarifies the reason and context. The many greetings back and forth show us a Paul who is staying in Corinth for a while. He has been reconciled with the community there and has had time to write a widely supported letter to their mutual friends in Rome and the church there. Just as Paul had made an effort to reconcile himself with the church in Corinth, he also wants to confirm the relationship with their friends in Rome.

At the same time, the same issues must have been at play there as well. Anyone who reads the Epistle to the Romans will quickly see that chapters 4 through 9 in particular are a further elaboration of Galatians 3 through 5: faith and the law, the justification of the uncircumcised Abraham and the promise to all nations, baptism as dying with Christ, discovering God as "Abba, Father," life through the Spirit, and the election of Isaac. You also see that the lessons in the letters to the Corinthians about Jesus as the second Adam, about the church as the body, and about the strong and weak in faith are given a place. This means that the situation in Rome is similar to what we saw in Antioch, Galatia, and Corinth: the church was confronted with the question of whether non-Jewish believers could participate fully or whether they would first have to adapt to Jewish law. In addition, you can see that Paul's story has grown through the objections he raised, especially from the Jewish side. The letter to the Romans is full of objections, which Paul then answers. In this letter, Paul has become a bit more balanced and milder. He will even write that the law is holy, righteous, and good.

Paul knows how difficult this subject is. He has the scars to prove it. But it is also his life's mission: that Jews and non-Jews be saved together in Jesus, that the mixed congregations among the nations be an instrument in God's plan to bring all peoples to conversion and thus also save Israel. To this end, the Jewish believers in Rome must make more room for the Gentiles, dare to let go of their sacred rules, and not immediately condemn the different morality of the Gentiles. The Gentiles, for their part, must not look down on what they consider to be the uncivilized and illogical Jewish faith.

Phoebe

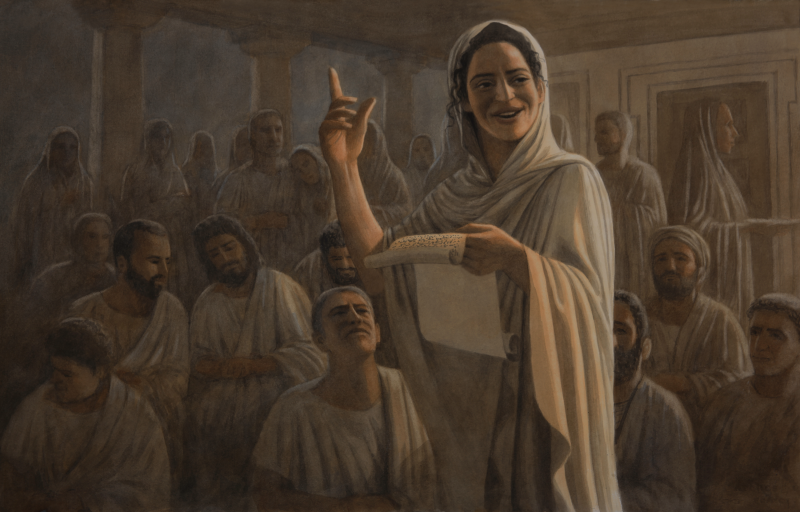

Paul therefore sends a letter with the approving stamp of as many mutual friends as possible. He asks Phoebe, a deacon or "servant" who leads the church in the Corinthian suburb of Kenchreeën, to deliver the letter as his emissary. This is an important task. She will have to give Paul a difficult sermon of about an hour. She will have to answer questions and convince people.

I imagine that Phoebe and Paul practiced extensively. Febe knows where to push and where to pause, where to sound ironic, where to suddenly turn around and look the Jewish followers straight in the eye, and where to address the newcomers from other nations. It is a form of performance art that we unfortunately miss when we read the letter today. And we miss Phoebe most of all in the first chapters.

Phoebes opening act

In Romans 1-3, Paul addresses mainly Jewish believers: "But if you are called a Jew, and if you rely on the law, and if you boast about God and know His will..." He continues: "Are we somehow better than other nations?" In chapter 4, he begins talking about "our father Abraham," and in chapter 7, he says, "I am speaking to people who know the law." It will be 11:13 before he specifically addresses the non-Jews in his audience.

So the big question for Paul is how he can motivate the Jewish followers of Jesus in Rome to truly want to form one community with non-Jews so that the gospel can also break through to all nations in Rome. To do this, he, or rather Phoebe, must shake them awake.

Imagine, therefore, that you are a Jewish follower of Jesus and are present in the house of Priscilla and Aquila. At the beginning of the meal, they ask for a special welcome for Phoebe, a businesswoman who has just arrived from Corinth, a journey of over 1,200 kilometers by sea and land. Phebe is praised for her work for the church in Corinth and in particular for her work for the poor there. Tonight she will read a letter from Paul from Corinth. The people are curious, because many know Corinth and have friends there. They have heard that there was considerable controversy surrounding Paul, who initially seemed to set aside Jewish law and then intervened in a scandalous case of sexual misconduct. Copies of his letters had already reached Rome, and what they understood from them did not bode well.

After the meal, the hostess gives the floor to Phoebe. "It has become a long letter," she apologizes, "I will begin right away." The opening of the letter is well received: this is the gospel as you know it: Jesus is the son of David who was raised from the dead by God's Holy Spirit. That is why he is the Lord who will come again to restore Israel. And you appreciate that Paul has truly given everything to bring this message to Jews and non-Jews among the nations—he sounds a little (let's not exaggerate) modest! Paul writes about his desire to come to Rome to encourage and be encouraged. It helps, by the way, that Phoebe is reading it aloud; her voice is pleasant and everyone respects her.

“For I am not ashamed of the gospel: it is the power of God for salvation to everyone who believes: first to the Jew, then to the Greek. For in it the righteousness of God is revealed from faith to faith. As it is written: ‘The righteous shall live by faith.’”

She looks up and smiles: "You know these words of the prophet Habakkuk, of course: 'By whose faith shall we live?'" To be honest, you had forgotten. But now you remember the discussions of the rabbis: do we come to life because of God's faith in us, or because of our faith in God? Or both?

Phoebe reads in the church of Rome. © Balage Balogh, Archaeology Illustrated.

Then Phoebe continues with a completely different message, and she immediately sounds much more serious: "For from heaven the wrath of God is revealed against all ungodliness and unrighteousness of men who suppress the truth in unrighteousness." Why such seriousness, you might think. For many Jews, the Day of Judgment is primarily a celebration: payback for the pagans who oppress Israel.

Febe does her best to emphasize the words so that you immediately hear the difference: in the Gospel, God reveals how He makes things right with us, but "from heaven," that is, from the cosmic consequences of the injustice that people do, God's disapproval is revealed. And rightly so, you think, when you see that many of you are struggling in Rome, that your parents or grandparents were brought there as slaves, that you live without civil rights—while a few hundred wealthy Roman families oppress and exploit the entire world so that they can live here in unprecedented luxury and degenerate lust!

“They are beyond excuse,” Phoebe exclaims, and you nod. “They exchanged the glory of God for images of mortal men and beasts; therefore God gave them over to the impure desires of their hearts. They have exchanged the truth of God for a lie; therefore God has given them over to unnatural lust, men with men, so that their wives have been given over to one another.” Amen, yes, that’s how they are, you think. They are getting what they deserve.

"They are full of jealousy, murder, strife, and deceit," Febe now works toward a kind of climax: "They are thoughtless, unfaithful, unloving, and merciless. Even though they know that they deserve the death penalty from God, they encourage others to join them." Febe falls silent. She looks at you and adds: "Yes, even we go along with it. While we speak shamefully of it, we long for their power and abuse the little we have ourselves." There is complete silence.

She picks up the letter again and continues reading: "Therefore, child of man, you have no excuse when you judge them. For with the judgment you pass on them, you pass judgment on yourself." And you vaguely remember these words of Jesus, but you forgot them as soon as you were reminded of the pagans with their many sins.

How often have homosexuals been condemned with Romans 1:26 and 27? How often has Paul been condemned because of the intolerance we thought we read there? But anyone who reads it that way has completely missed the point of Paul's argument. Consider this: "When you point your finger at someone else, three fingers are pointing back at you." Did you really think that you did not need forgiveness, that you could rely on your Jewish roots and a virtuous life? Paul goes through two more depressing chapters to hammer the point home: for God, there is no difference between Jews and non-Jews. Even the Jewish holy books say so: everyone sins, everyone lacks God's presence. If you remain in the logic of judgment, you remain hopelessly lost.

But fortunately, after concluding that you can never make your sinful flesh righteous through the "works of the law," Paul returns to his summary of the gospel. Finally, a ray of light breaks through. And you can hear it in Phoebe's voice:

But now, apart from the law, the righteousness of God has been revealed, as attested by the law and the prophets: the righteousness of God through faith in Jesus Christ [in God], for everyone who believes [in him].

So, that is what was meant by "from faith to faith," or "from belief to belief," as it is usually translated. Paul does not see faith as a means of selection to save a small group. For him, it is the power of God through which many come to discover what true life is. From the trust that Jesus placed in God, the nations and ultimately all of Israel learn to trust God again.

Learning not to judge

After this spectacular and intense opening, Paul turns his attention to rephrasing his familiar themes. Abraham was already righteous before God when he was uncircumcised and is thus the father of circumcised and uncircumcised peoples (chapter 4). Christ died for us while we were still sinners, in order to redeem humanity from sin and death as the antithesis of Adam (chapter 5). Through baptism, we share in his death and life (chapter 6). The old "man" who was under the law has symbolically died; you, his wife (a reference to the soul, because psyche is a woman's name), are no longer under his authority. You are now, as the bride of Christ (chapter 7), under the authority of his Spirit. This is not a Spirit of slavery, but a Spirit who recognizes us as children of our abba, father, and restores our bond with God unbreakably (chapter 8).

The grand plan that Paul sees

On this basis, Paul can discuss God's plan of salvation for Israel and the Gentiles in chapters 9 through 11. It seems unfair and arbitrary how God sometimes draws the Jews to Himself and sometimes the Gentiles. But Paul defends God's freedom and sees a greater plan. Because of Israel's unbelief in Jesus, the apostles, and Paul in particular, were sent to the nations. When the nations are saved, Israel will understand God's plan and will still be saved in its entirety. That is the resurrection of the dead that he looks forward to. Paul sees balance and reciprocity, so that no one needs to feel better than anyone else. This—and here he addresses the Gentiles directly—also deprives the Gentiles of any grounds for contempt toward the Jews.

Conclusion

In chapters 12 to 15:13, Paul arrives at his conclusions and exhortations: The church is a body in which we can function precisely because of our different gifts. But that is only possible if we love one another with one mind and treat outsiders and authorities with respect and kindness.

In chapters 14 and 15, Paul calls on Jews and non-Jews, the "strong" and the "weak" in faith, not to judge or despise one another. Not that this is easy; Paul himself struggled with it. But who are we to judge another servant of God? Let each of us be accountable to God in his own conscience, for Christ will judge the living and the dead. Paul presents his conclusion in a beautifully composed paragraph:

So you, who judge your brother, or you who look down on your sister,

We will all stand before the judgment seat of God.

For it is written: As surely as I live, says the Lord,

every knee will bow before Me,

and every tongue will confess to God.

Then each of us will give an account of ourselves to God.

Therefore, let us no longer judge one another, but rather judge this: that you do not give your brother or sister cause for stumbling.

Learning not to judge is what the Letter to the Romans is all about.

Salvation

In the hands of Augustine and Luther, struggling men who recognized themselves in Paul's dramatic conversion story, the letter to the Romans became preeminently a letter about human shortcomings and God's undeserved grace. You experience this the moment you believe in Jesus, namely that the Son of God died for your sins. In the Protestant tradition, this has made the image of God as judge very central, whereas the great innovation of Jesus was precisely that God is our abba, Father. And you can read that in Romans too. It is increasingly recognized that Paul writes not only about faith in Jesus but also about Jesus' faith that restores the bond between God and humanity: his trust in God and his faithfulness to humanity is the way to salvation. Perhaps you could also say that those who are no longer afraid of God as judge can learn to trust him as a loving father, and vice versa.

There are many ways in which Paul and the other writers of the New Testament try to express their experience of salvation. In the table below, I have distinguished a few, but in the New Testament these images often flow into one another and enrich each other.

Summary: Learning not to judge, mid-50s.

In Corinth, things are settling down. Paul is welcome there. But he does not find all his friends there. In the year 54, Emperor Claudius died, and it may be that many expelled Jewish followers of Jesus were therefore able to return to Rome. Paul writes a letter to them to explain how he understands the Way and the Second Coming, and how the church in Rome can also contribute to the advancement of the Gospel among all nations.

- You read the Letter to the Romans very differently once you see that Paul is primarily asking Jewish followers not to judge people who do not know the Law, while asking non-Jewish followers not to look down on the devout. No one is without sin, no one can do without grace. In this letter, Paul repeats the most important themes from his letters to the Galatians and the Corinthians, addressing the counterarguments he has received in recent months and years. But he also sees a divine plan: the gospel is spreading to the nations because not all Jews accepted Jesus as the anointed Messiah, the Christ. But it is precisely the influx from the nations that will stir Israel to seek God. In this way, all nations, including Israel, will be saved. Hence the importance Paul attaches to the collection for Jerusalem, even though he is concerned about whether he will be accepted there.

Rome, the forum with the Basilica Julia and the Basilica Aemilia.© Balage Balogh, Archaeology Illustrated.

A bit of background: Prejudice against Jews in Rome

If you want to understand the situation of Jewish people in Rome in the first century, it might be best to visit a mosque in a migrant neighborhood in Western Europe. There you will meet parents who are concerned about the unbelieving and sexualized society in which they have to raise their children. Many came here without education or contacts to work at the bottom of society. Some did very well and rose to positions of leadership. Some lost their jobs and ended up unemployed. For many, it was difficult to eat halal and live according to their beliefs, to go to the mosque on Fridays, and to find a marriage partner who shared their values. Later, they opened their own shops, and for many women, wearing the veil became a conscious choice for their own identity. All of them suffer from disadvantages, prejudice, and discrimination. A few translate this into a sometimes radical rejection of the "West" and its associated "values."

Tacitus

We can read about how negative these prejudices against the Jews were in Rome in a book by Senator Cornelius Tacitus, written around the year 110:

"In order to maintain a firm grip on the people in the future, Moses introduced new religious practices that were contrary to those of other peoples. What is profane to them is sacred to us, and conversely, everything that is taboo to us is permitted to them. (...)

They abstain from pork in memory of their plague: they themselves were once afflicted with scabies, a disease to which this animal is also susceptible. They commemorate their former famine with frequent fasting, and as a symbol of the corn that was hastily harvested, Jewish bread is unleavened. The seventh day is a day of rest, they reportedly decided, because it brought an end to their labors; later, blessed idleness led them to devote the seventh year to leisure as well. (...)

Regardless of their origin, these rituals are justified by their age. Other customs, wrong and repulsive, are strongly rooted in their wickedness. (...) They are usually merciful to each other but harbor hostile hatred for all other people. At table and in bed, they remain separate from others. Despite their excessive sexuality, they avoid sexual intercourse with non-Jewish women, but among themselves, anything goes. They have instituted circumcision as a clear distinguishing mark.

Those who convert to their culture adopt the same customs. The first thing they are taught is to despise their own gods, to renounce their homeland, and to treat their parents, children, brothers, and sisters with contempt. Nevertheless, they think about increasing their numbers. For killing any child born after the first is taboo, while the souls of those who fall in battle or by execution are, according to them, eternal. Hence their love of procreation and their contempt for death.

(...) Egyptians worship numerous animals and hybrid creatures, while Jews know only one god, and that only in spirit. They consider anyone who makes images of God from perishable materials and in human form to be profane; their supreme, eternal being can neither be depicted nor limited in time. That is why they do not erect statues in cities, let alone in temples; princes are no longer flattered, Caesars are not honored.

(...) [The rituals] of the Jews are absurd and filthy."

Add comment

Comments