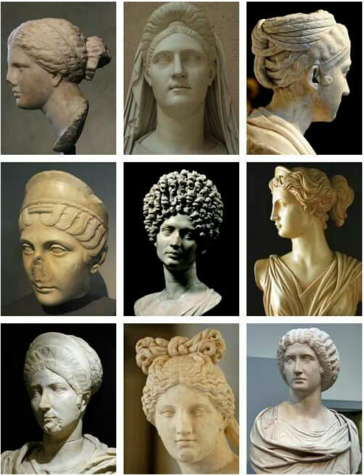

Ephesus and Corinth, the early 50s

Introducing: Jude, I and II Corinthians, I Timothy and Titus

Paul finds a new home with his friends Priscilla and Aquila in Ephesus, the capital of the province of Asia. He stays there for a few years and remains in close contact with the growing number of churches around the Aegean Sea: Crete, Achaia, Macedonia, Asia, and Galatia, through short visits and letters.

The major problem during these years is the relationship between the radical freedom and equality in the letter to the Galatians and the need for a healthy and constructive lifestyle in harmony with the Greek-Roman and Jewish environments. How do you live in freedom when so many people live according to their own instincts and desires? How can that work within a household, within a religious community, or within a city? And how do you do that in light of the Lord's soon-expected return? What is still important now?

Ephesus, the capital of the province of Asia, now part of Turkey. © Balage Balogh, Archaeology Illustrated.

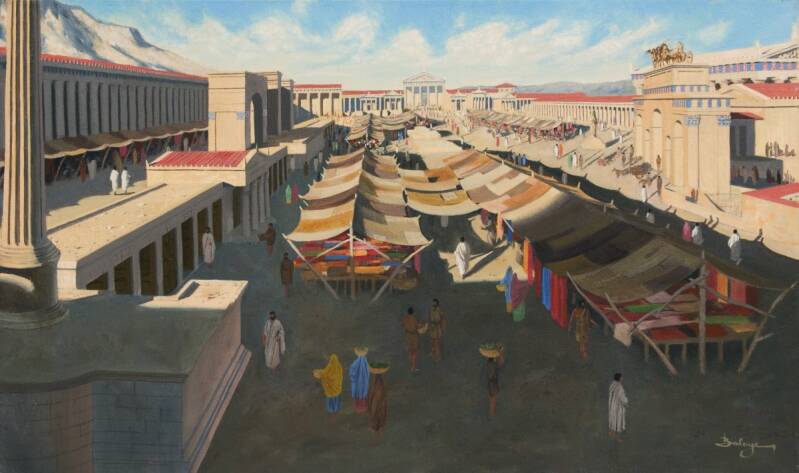

The letters to the Corinthians, which Paul wrote from Ephesus, among other places, reveal the practical problems that had to be resolved in order to move from the breakthrough in the letter to the Galatians to the balanced argument in the letter to the Romans. There are numerous differences of opinion. Some follow Jewish law, others follow civic morality, and still others claim to be free from all of these. Some appeal to Peter, others to Paul, and still others to Apollos. And if you follow Jewish law, are the non-Jewish but baptized followers of Jesus pure enough, kosher enough, to eat with or marry? And what about their unbaptized housemates who may have touched the food with their fingers? Some believe that you should live traditionally and with common sense: build a nice family and be a good citizen. Others believe that it is pointless to get married when Jesus is coming to take us to God, where we will live like angels who do not marry or are not married off. Some even believe that marriages should be dissolved now and that people should stop having sex, while others claim that it no longer matters how many people you have sex with or what kind of people they are.

In the young church of Corinth, less than five years old, the problem became acute when a young man actually moved in with his stepmother, his father's young wife. Is that acceptable in a church when it is a mortal sin under Jewish law? We don't know for sure if it had anything to do with it, but the church members took each other to court. The entire city, and far beyond, spoke shamefully of the freedoms that the followers of Jesus thought they enjoyed.

I Corinthians

The letters to the Corinthians are so rich in imagery, insights, personal information, and cultural details that it is difficult to grasp the main thread. All too quickly, we limit ourselves to a beautiful passage or something that annoys us. This is where listening to a reading comes in handy, as it allows you to give each passage equal attention. But even then it remains difficult: we only hear part of the conversation, and only Paul's side, as if you were sitting next to someone in the middle of a telephone conversation. To help you on your way, I will go into the content of the letter in more detail here.

This letter was preceded by the necessary visits and letters back and forth. It seems that Chloe's housemates (apparently a wealthy lady) and Stephanas and his companions expressed their concerns about the division, immorality, and points of contention in Corinth. A letter has also been brought from Corinth with the necessary questions (you immediately wonder which groups wrote the letter, but unfortunately that remains unknown). Paul writes the letter with Sosthenes, a former synagogue leader in Corinth. Perhaps that helps. He also wants to strengthen Stephen's authority and sends Timothy as his own representative.

Imagine that the letter is read aloud in this divided community of Jews and Greeks. Then you immediately understand why Paul has to devote four chapters to laying a solid foundation: seek unity! All those apostles, such as Cephas (the Aramaic name for Peter), Paul, and Apollos, are only servants and helpers. It is about Jesus as God's anointed one, the Messiah, and then – totally unexpected – as the crucified Messiah (Christ in Greek). That is either an idiotic idea, a blasphemous disgrace, or a sign from God that we must learn to think differently. Unfortunately, it is lost in our translations, but in the Greek of the letter, Paul distinguishes between people who are led by the instincts of "the flesh" and find it idiotic, or by the emotions of "the soul" (psyche) and find it scandalous, or by the Holy Spirit and find in it the revelation of God's wisdom. That is why he asks people not to judge him, but to leave that judgment to the Lord. In fact, he asks them to accept him as a loving father who may admonish and punish them when necessary. This leads him to questions and points of criticism in chapters 5 through 15.

>> Now would be good to read I Corinthians 1-4

Sexual immorality

Chapters 5 and 6 deal with sexual immorality. It is painful for Paul, but his own message, "everything is permissible," is abused by people to allow their fleshly desires to rule over them, even if it destroys them. And yet others believe that you should not say anything about it. Imagine, then you could also say something about their prostitution! "Everything is permissible for me," Paul replies, "but not everything is beneficial. Everything is permissible for me, but I will not be dominated by anything." Specifically, this concerns the young man who has moved in with his stepmother. Paul, as if he were present in the congregation reading the letter aloud, delivers him, together with the listeners, to Satan, because the congregation must judge its own members. The aggrieved party, presumably the young man's father, should not have to go to court to obtain support. What? What is this about? you may ask. Fortunately, we will hear more about this in II Corinthians, otherwise you might draw some very strange conclusions.

Questions from the community

Chapters 7 through 11 deal with specific questions from the letter to Paul. Now Paul must be very careful: how can he connect his message of radical liberation with the rules in very concrete situations that they are asking him about? Like a true rabbi, he lets them see his thought process: follow my example, as I try to follow Jesus. And he visibly struggles: when do you use arguments from the law, from the words of Jesus, from "nature," or from what "even the pagans" find scandalous? When do you use your own opinion, and what is it worth?

- Should you still get married? The first question, chapter 7, is far beyond our experience. It concerns the opinion of some that it would be better to stop getting married, or at least stop having children, in light of the imminent arrival of Christ. This immediately solves the problem of "uncleanness" in mixed marriages with unbelievers (non-Jewish or unbaptized). Didn't Jesus say that we will then be like the angels with God who neither marry nor are given in marriage (Mark 12:25)? Paul, himself unmarried, finds it a logical idea, but knows that Jesus himself spoke out against divorce. From this he concludes that you are called as you are (whether married, circumcised, or enslaved), and that you do not have to change that at any cost. The Lord is coming soon, Paul believes. Besides, he doesn't think the issue of uncleanness is that serious: otherwise, you wouldn't even be able to eat with your unbaptized partner and children!

- What is kosher for Jesus followers? Chapters 8 through 10 deal with food and directly touch on Paul's conflict with Peter in the Epistle to the Galatians. If you can eat anything, can you even eat meat from animals that have been slaughtered for idols? After all, most animals in the city were slaughtered while invoking one god or another. Paul is now much more nuanced than in his letter to the Galatians. "Knowledge puffs up, but love builds up," he begins. His conclusion: "I may eat anything, but if a brother or sister is troubled by it, I would rather be a vegetarian." He realizes that criticism is coming from all sides. Peter's followers accuse Paul of often eating what his hosts served him, including sacrificial meat. But his former allies consider him a turncoat and cry out, "Then you are not free from the law either." Paul defends himself. To one group he says: I am free to live with Jews as a Jew and with non-Jews as one of them. I do everything to bring people the liberating message of Jesus. Life is a race, he warns, don't think you've already arrived. Like Judah in his letter, Paul warns against idolatry and sexual immorality from the time of Moses, after the exodus from Egypt. "Everything is permissible, but not everything is beneficial. Everything is permissible, but not everything builds up."

- Can a married woman let her hair hang loose? Chapter 11:2-16 deals with a related issue: the Jewish and non-Jewish tradition that married women should wear their hair up or covered in public. Only young girls, slaves, and prostitutes walked around with their hair down. Why were there women in Corinth who let their hair down while prophesying or praying in the church? Did they want to show that they had been born again? Were they renouncing marriage? Here too, Paul takes a middle ground: it is better not to do it, he seems to say. On the one hand, he sees a hierarchy from woman to husband to Christ to God; on the other hand, men and women are nothing without each other and equal in Christ. I also suspect that Paul, as in his letter to the Galatians, simply means by his reference to "angels" that such rules in the law and tradition were not divine and eternal, but temporary and culture-bound; merely "commandments of angels." In any case, he asks his audience to use common sense and not to quarrel.

- How do you celebrate the Lord's Supper so that it is a meal of love? The second part of chapter 11 is about the Lord's Supper: how do you ensure that everyone shares with each other and that the memory of Jesus' last supper is central? In this section, you will find the early tradition of Jesus' words.

>> Now would be good to read I Corinthians 5-11

The roles in the church and love

The famous chapter 13 about love really needs to be read together with chapters 12 and 14 before and after it. For Paul, love is the royal road out of our human limitations. Even, and perhaps especially, in our pursuit of spiritual gifts and our role in the meetings, we stand in our own way. Paul returns here with his radical vision of equality and diversity in and through the Holy Spirit, with his metaphor of the church as the body and the enduring value of faith, hope, and love. Chapter 14 provides a unique insight into the meetings of Jesus' followers, in which Paul asks that common sense be used alongside these exuberant gifts. Verses 34 and 35 have often been misused to silence women in the church, but that is an impossible interpretation, since Paul says that everyone may contribute, while in chapter 11 he also spoke of women praying and prophesying. It has therefore been suggested that this passage was inserted later, or is a quotation from one of the groups in Corinth, or only applies to wives who should not question their prophesying husbands critically.

The resurrection

Chapter 15 answers the question of a group in Corinth who cannot believe in the physical resurrection at the Lord's return. That Jewish belief was a bridge too far for many Greeks and Romans. Paul saved this question for last because here he can show how much he is in line with the other apostles, with Peter (Cephas) and James. That is why he gives us here the ancient tradition of the witnesses of the risen Lord. Jesus died in his earthly body in order to be able to give life to everyone everywhere in his spiritual presence. If everyone, including Paul's opponents, agrees that Jesus rose from the dead, then surely you cannot be fundamentally opposed to the resurrection from the dead? Paul does admit, however, that the resurrection body cannot be the same as our earthly body, just as the heavenly kingdom of God is not the same as this world.

Paul ends in chapter 16 with the collection for the poor in Jerusalem and his changed travel plans.

>> Now would be good to read I Corinthians 12-16

The Letter of Jude

It is important to understand the disapproval that sexual immorality, as in Corinth, evoked among other leaders of the churches. The Letter of Jude, Jesus' second youngest brother, who is believed to have written the second to last book of the Bible, provides a good insight into this. Of course, we have no way of verifying this, because all we know about Judas, or Judah in Aramaic, is that his grandchildren still played leading roles among the Jewish followers of Jesus in Israel in the second century. Many theologians date it to around the end of the first century. But if we go by the text itself, it refers to Judas, "a brother of James and a servant of Jesus." In 1 Corinthians 9:5, Paul reports that Jesus' brothers and their wives also traveled around the churches. Judas' short note can be read as an expression of this.

This Judas had intended to write a letter about what united the churches in Israel with the churches around the Mediterranean: their common salvation. But now (he suggests recent and surprising reports) he feels compelled to write a warning letter against licentiousness within the churches, among those who defile the Lord's love feast. As we already understood from Paul's letters at that time, it seems that the freedom in Christ is being seized by some to justify sexual immorality with an arrogant theology that rejects the authority of Moses, the angels, and the Lord himself. Like Paul in 1 Corinthians 2:14, Judas calls such people "psychic" in verse 19: they are led by the passions of their soul (psyche) rather than by the Holy Spirit. They blaspheme what they do not understand, and what they think they must do damages them.

Jude uses examples from the Bible and related writings (which are not in our Bibles) that would have meant something to Jewish people in his day. Don't think that your choice for Jesus and your baptism are enough: even the angels before God's throne and the Israelites who left Egypt could still be lost because of their lack of faith and unfaithfulness. Do not become like Cain, who listened to evil and killed his brother, or like the prophet Balaam, who led the Israelites away from God with fornication, or like Korah, who instigated a rebellion against Moses and Aaron! Let yourself be guided by God's Spirit, hold fast to his love and the mercy of Jesus, so that you may appear before him with joy.

The letter of Jude is not diametrically opposed to Paul. Paul also speaks out against sexual immorality in Corinth and points to the same example in the Law. He too warns against celebrating the Lord's Supper in an impure manner and dealing with the gospel in a "psychic" way. And unlike Cain, he does not want a brother to be lost because of his actions. But you can understand the pressure on Paul and his supporters when their followers abuse their freedom for debauchery.

The crisis in Ephesus

Ephesus was a religious and tourist center. The Temple of Artemis was considered one of the Seven Wonders of the World, and goldsmiths sold statues of the goddess and her temple. But because of Paul's preaching and the pagans he converted, they were confronted with fierce discussions and loss of income. Paul was dragged by an angry mob to the public assembly in the city theater. Greeks felt threatened by the conversion success of this Jewish preacher. Greek women, children, and slaves were turned against their pater familias. "A fight with wild beasts," he called it in his first letter to the Corinthians.

But it did not stop there. The Jewish community was pressured to distance itself from Paul. Alexander the silversmith, a Jewish colleague of the goldsmiths, started a smear campaign against Paul: He is disrupting social relations in Ephesus, he is said to have said. And that while the new movement is far from squeaky clean, just look at the debauchery in Corinth! "We were persecuted beyond our strength," Paul would write in his second letter to the Corinthians. He feared he would be sentenced to death. But he escaped death and left the city in great haste.

The Letter to Titus and the First Letter to Timothy

You can read Titus and I Timothy as a response to the licentiousness within the churches and the tensions that this caused in the cities, among the Jewish communities in those cities, and among the other followers of Jesus. These "pastoral letters" are seen as a correction to the radical elements in Paul's thinking that some believers could exploit. And for that, you need structures and overseers.

However, the vast majority of theologians believe that the letters to Titus and Timothy were written decades after Paul's death. The language, theology, and focus on structures and offices are far removed from the letters to the Thessalonians, the Galatians, the Corinthians, and the Romans. A small minority do not find these arguments strong enough and do consider the letters to be those of Paul. After all, Paul could have used another "ghostwriter." The nature and context of these letters, addressed to his own co-workers, are of course also different. Moreover, in Philippians 1:1, Paul specifically greets the overseers (bishops) and deacons of the church; this is therefore already an existing structure.

Of the theologians who do consider the letters to be genuine, many are inclined to place them after the end of Acts, which makes no mention of a trip to Crete. A few point to another possibility because Timothy still has little authority in the letter due to his age (1 Tim. 4:12 and 5:1). That comment is really only appropriate in the 50s. Timothy was still in his twenties at that time, and Titus would not have been much older. Their roles also fit the picture that emerges from Paul's other letters: in 1 Corinthians, Timothy is appointed as Paul's representative, and Titus in 2 Corinthians. The letters can therefore be read before or between I and II Corinthians, when tensions are running high everywhere:

- In Titus, Paul had previously been to Crete, where he left Titus behind. Paul wants to spend the winter in Nicopolis, perhaps coming from Illyria or on his way to Corinth. He anticipates that he will send a messenger such as Artemas or Tychicus to Titus with his final instructions.

- In 1 Timothy, Paul has just left for Macedonia and left Timothy behind in Ephesus to lead the church there despite his young age until Paul returns.

The letter to Titus continues the story of Apollos. We know the name Apollos from 1 Corinthians 1-3 as one of the three leaders with whom the different groups in Corinth identify: one group follows Paul, another Kefas/Peter, and yet another Apollos. Apollos, who comes from Alexandria in Egypt, also travels around Asia and Achaia and is now in Crete. Paul wants him to go to Corinth (1 Corinthians 16:12), but he apparently wanted to go to Crete first. In Titus 3:13, he asks Titus (who may have come from Corinth) to help Apollos and the Torah teacher Zeno on their way. The language used here also testifies to the competing groups: Paul speaks of "our people" as if Apollos and Zeno do not belong to that group.

The first letter to Timothy begins the story of Paul's opponents in Ephesus. We hear about Hymenaeus and Alexander, whom Paul has handed over to "Satan" (just like the adulterous son in 1 Corinthians). We will encounter them again later in the second letter to Timothy and in the book of Acts.

Anyone who wants to read these letters at the time they were presented (regardless of whether they were actually written by the historical Paul) can best interpret their special nature and content as "mandates." You then see a Paul who cannot be everywhere at once to resolve the crisis. With his letters, Paul mandates his young co-workers to put things in order on his behalf and install stable leadership. As letters of mandate, these letters must be read aloud in the churches to position Titus and Timothy correctly: Paul identifies the problems that exist locally and sets out a strict mandate so that the young men have the space and support to act. The structures Paul has in mind resemble those of the synagogue, with elders and social-pastoral workers: deacons and widows.

The letters are therefore very conservative: male leadership, based on the existing social relations in the Greek-Roman cities (with patriarchy and slavery!) and the promotion of sobriety, piety, and chastity. The Paul of these letters is concerned with leadership that has authority both within and outside the church, both in the city and within the Jewish community. We may find this very annoying today, but we can also see it as the preconditions for functioning in a concrete context and bringing the gospel to people. Think of it as the walls of the house within which the real life of equal women and men, slaves and free people can flourish.

Anyone familiar with the (uncontested) letters to the Galatians and the Corinthians cannot therefore give priority to the rules in these letters of mandate over love. For Paul, love is divine, guiding, and enduring; the rules are human, supportive, and temporary. So there is something to be said for people today choosing different structures and rules that are more suited to our times, based on love. After all, Paul is concerned that people be protected from abuse and that outsiders be reached with the good news of God's love.

The Second Letter to the Corinthians

Many people today consider I Corinthians to be a beautiful letter, but in Corinth it was completely misunderstood. The question is how much of Paul's instructions they immediately adopted. Timothy returned to Paul with alarming news: "A large group in Corinth has completely turned against us. They disagree with your condemnation of one of their church members, they think you are fickle because you changed your travel plans, and they distrust your intentions with the collection."

Then things also go wrong for Paul in Ephesus. He fears for his life. The shocking events still reverberate in his writing. Paul leaves for Troas and sends Titus to travel via Corinth. He waits anxiously for Titus' arrival, but he is delayed.

Only in Macedonia does Titus join them with reasonably good news: the majority in Corinth has agreed with Paul's condemnation of the fornicator and with participating in the collection for Jerusalem. Others are still fiercely opposed to Paul and say that he is not an apostle at all, unlike the Jewish apostles who personally followed Jesus in Galilee and Jerusalem. Paul and Timothy then write II Corinthians and give it to Titus, who immediately returns to Corinth to prepare for the arrival of Paul and the representatives of the giving churches in Galatia, Asia, and Macedonia.

The mixed feelings in Corinth and among Paul led to a letter with such divergent moods that many theologians believe that II Corinthians is composed of two, three, or even five different letters. They also point out that in one part of the letter, Paul seems to have already returned to Corinth, while in another part he has not yet done so. This view is also reflected in modern translations of the letter. But you can also read the Greek differently, in the sense that Paul seems to be playing with being present "in spirit" and physically returning, with being ready for the journey three times and only arriving twice. It is important to note that the Greek-speaking readers of this letter in ancient times read it as a whole, written by a Paul who, as you could also translate it, postponed his visit because he did not want to "return in sorrow" to Corinth. The story in the final letter as we have it now therefore fits in with their image of Paul and the early church. Paul then writes a letter in which he expresses his joy at the majority who want to continue with him and the collection, while admonishing the minority who reject him. In doing so, he reveals a great deal about himself in order to change their minds. "Allow me to boast a little," he says. And from this we learn once again how Jewish the whole discussion actually is: The competing envoys were Israelites, and so was Paul—five times he was punished as such by a local Jewish community with 39 lashes (a specifically Jewish punishment). This means that the image of Paul as an apostle to the nations cannot be separated from the Jews who lived among those nations.

The beautiful thing is that it ended well for our fornicator and his stepmother—and perhaps also for the father: Paul speaks of "the one who did wrong" and "the one who suffered wrong." Titus reported that the majority had condemned the young man with pain in their hearts and broken off contact with him (7:8-12) – that was apparently what Paul meant by the painful and sad instruction in 1 Corinthians 5:5 that they should "hand him over to Satan" in order to save him. Subsequently, the young man did indeed repent, so that Paul now calls on the people to forgive him wholeheartedly and to accept him back in love (2:5-11). In this way, you prevent Satan from winning. In this way, the church remains a place where the Spirit of God's love is leading.

Summary: Love and debauchery, mid-50s.

Paul's revolutionary teaching is immediately put to the test in Corinth. If the law was temporary and everything is permitted, what do you say to the young man who commits adultery with his father's young wife? People from Corinth come to Paul in Ephesus to tell him about the divisions in the church: some want Paul's radical freedom (everything is permitted), others follow the traditional fisherman Peter or the lawyer Apollos.

- In I Corinthians, Paul answers numerous questions from the church. He points to love as the bond that holds the body together, but demands that they expel the adulterous young man. He also announces a collection for the poor in Jerusalem.

- If you read the Letter of Jude, the brother of James, the brother of Jesus, you can see how concerned he is about the lack of moral awareness. He warns them that this could end badly.

- The letters Titus and I Timothy also tell of a turbulent time in which the churches around the Greek Sea are discredited and threaten to fall apart. Paul has to leave Ephesus and sends his young co-workers on their way with strict letters instructing them to try to restore order in Ephesus and Crete on his authority.

- In II Corinthians, we read that Paul's actions and letters have not been well received everywhere. Paul has to explain that he had to change his travel plans because of the riots surrounding him in Ephesus. He is now traveling to Corinth via Philippi and Thessalonica. Paul's opponents find him fickle and boastful. But you also read that the adulterous young man has repented, and Paul asks the congregation to take him back lovingly. He announces that the collection for Jerusalem will go ahead and that he wants to undertake that journey from Corinth.

The market of Corinth. © Balage Balogh, Archaeology Illustrated.

A bit of background: Travel plans and travel in the years 53-56

Readers who read II Corinthians as a single letter could understand Paul's travels and travel plans as follows from the letters themselves (again, without using the book of Acts):

- Paul, Titus, and Timothy work with Priscilla and Aquila in Ephesus, the capital of Asia (1 Corinthians 16:19). His stay in Ephesus is not without conflict; he writes that he fought with "beasts" there (1 Corinthians 15:32). Around this time, they also traveled on to Illyria (Rom. 15:19) – or the southern part of it under the name Dalmatia, where Titus later returned (2 Tim. 4:9).

- Option 1: Here you could place the trips to Crete and Macedonia in Titus and I Timothy.

- In Ephesus, Paul receives a visit from Sosthenes from Corinth with a letter from the church. Paul also hears that the church in Corinth is divided: some support Peter, others support him, and still others support Apollos, a teacher who worked in Corinth after Paul (1 Cor. 3:6) and then with Paul in Ephesus (1 Cor. 16:12). Together, Paul and Sosthenes write 1 Corinthians in response. Timothy will also go to Corinth as Paul's emissary (1 Cor. 4:17 and 16:10). Paul's travel plans have changed again in this letter: he now wants to stay in Ephesus until Pentecost, go to Macedonia, and then spend the winter in Corinth. But Timothy returns to Paul with bad news: the letter has not been well received by everyone.

- Option 2: Here, too, you could place the trips to Crete and Macedonia in Titus and I Timothy.

- A major conflict arises in Ephesus, where Paul fears for his life (2 Corinthians 1:8). Paul asks Titus to come to him in Troas via Corinth—where he must defend him and save the collection—if he is on his way to Macedonia and Corinth (2 Corinthians 2:12-13). When Titus does not arrive in Troas on time, Paul crosses over to Macedonia (2 Corinthians 2:12-13). In Macedonia, Titus rejoins Paul with mixed news from Corinth (2 Corinthians 7:6). Paul and Timothy then write II Corinthians (2 Cor. 1:1) from Macedonia, a year after I Corinthians (2 Cor. 8:10, 9:2). Titus returns to Corinth with the letter to further promote the collection (2 Cor. 8:6, 17, 12:18).

- Paul follows him to Corinth (2 Cor. 9:4, 13:1). From Corinth, he then writes the letter to the Romans (as can be deduced from Rom. 16:23-24, where it refers to the same Gaius as in 1 Cor. 1:14 and the same Erastus as in 2 Tim. 4:20). Like many other Corinthian followers, Priscilla and Aquila have now returned to Rome (the decree banishing them ended with the death of Claudius in the year 54); in Ephesus, they had risked their lives for Paul (Rom 16:3). Timothy sends his greetings to them, among others (Rom 16:21).

- Paul travels to Jerusalem (Rom 15:25) and hopes to go to Spain via Rome (Rom 15:24).

Add comment

Comments