From the Sea of Galilee to Rome, in the 40s, 50s, and 60s

Introducing: Gospel of Mark

This is how they remember him in Rome: as a Galilean fisherman in his forties. Simeon Kefas, "the rock," was the name Jesus had given him. Along the way, his name changed to the Greek Simon Peter, although he found that a bit strange, because his Greek was mediocre and he didn't speak Latin at all. He had a young man with him, the nephew of Joseph Barnabas. In Jerusalem, he is called Jochanan, John to his Greek-speaking friends; in Rome, they call him Marcus.

Peter visits Jews who heard about Jesus when they were in Jerusalem on business and visiting the temple. Now he seeks them out, and they invite friends and family to hear the traveler from Jerusalem. Some of them know Jesus' sayings. Peter recounts the anecdotes and Mark translates them into Greek. He can recite many of the stories by heart, although you never know what twist Peter will give them tonight for this particular group of people. Sometimes, when Peter struggles to find the right words, Mark finishes his sentences for him. He is like a son to me, Peter would say.

Peter in the 4th-century catacomb of Thecla, Rome

The politics of the 40s

When Caligula was unexpectedly murdered on January 24, 41 AD, his friend Agrippa, a grandson of Herod the Great, pushed the stuttering Claudius onto the stage, where the soldiers cheered Caligula's uncle as the new emperor. The grateful Claudius made Agrippa king of all Israel. Agrippa no longer called himself after Herod, as he was also a grandson of the last Jewish queen from a glorious line of priest-kings. His coins bear the inscription "The Great King Agrippa."

The book of Acts tells how the new king wanted to please the Jewish leaders by beheading the apostle James (the brother of John). Peter was also arrested, but he escaped in a miraculous way and was hidden by the family of John Mark. As soon as possible, they send him to the coast. From there, he must have traveled on, at least until Agrippa died in the year 44 and Judea became a Roman province again.

Perhaps Peter traveled to Rome via Antioch. Both cities would later claim him as their "bishop," although that term meant something different in the first century than it did later. Perhaps the young Marcus left his mother Mary and went with Peter on his adventure. "Because of his gift for languages," they said. A church father writes that Peter arrived in Rome in the second year of Claudius. A Roman historian writes that a few years later, Claudius banished the necessary Jews from the city because of a dispute over a certain "Chrestos," which sounds suspiciously like "Christ" and was pronounced the same at the time. According to the book of Acts, some of them came to Corinth, a bilingual Roman colony in Greece, just as Paul arrived there around the year 49. It is striking how many greetings are exchanged between Rome and Corinth in Romans 16. Could this be true?

In any case, some of Jesus' followers in Corinth in the 50s are proud to be "of Peter": they have heard the gospel from him and some have been baptized by him. They even call him by his Aramaic name, Kefas.

Fish tales

The Gospels are full of stories that only a Galilean fisherman can truly understand. Someone like Mendel Nun, who became a fisherman at the age of 21 as an immigrant in Kibbutz Ein Gev on the Sea of Galilee. In 1939, he learned from Arab fishermen how to fish in the traditional way, using mirror nets, drag nets, and cast nets. They caught sardines, mullet, and barbel.

When Mendel Nun became an archaeologist, he discovered a wealth of information in the fishermen's Latin of Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John—if you listen to their stories and question them with the knowledge of a traditional fisherman and archaeologist.

The nets

They hadn't caught anything all night, Lucas says, but Jesus said, "Cast the nets on the other side of the boat." Then the nets were full of fish.

Some translate this as "cast the net," but that is not a good translation in this specific instance, we learn from Mendel Nun. Fishermen lowered the nets: double, mirrored nets that formed a wall around a school of fish. You chased the fish from the middle and they got caught in the double net. He had seen them: such an enormous school of fish seeking the relative warmth of the spring water flowing in at Tabgha, just outside Capernaum, in the winter cold.

The miracle was not that the nets were so full, but that the boys had caught nothing all that time until that landlubber was the first to see the school of fish. It felt as if God was telling them with that "miracle" that they should follow Jesus and—as Jesus said—become fishers of men.

The pillow

Towards evening, the boats crossed the lake. "Let's go too," said Jesus. But when the storm arose, he was asleep on the cushion, says Mark. On the other side, Jesus stepped out of the boat and found a man possessed by unclean spirits. Jesus drove them out, and a herd of pigs ran down the hillside into the water. It was not a Jewish area.

Did you have a cushion with you in the boat? you ask.

Mendel Nun replies: Jesus was sleeping on 'the balancing cushion,' as Arab fishermen still call it, a bag filled with sand that we used to keep the boat level in the water. It often storms in the evening on the lake, briefly but violently.

But why did the boats go out at night? you want to know.

They left at night to be in time for the sardines spawning on the sandbanks at Wadi Samakh, which is the biggest catch of the year. The larger barbel also came there to hunt the sardines. In early spring, they caught so much fish that salters could sell the salted fish as far away as Rome. They fished with dragnets hundreds of meters long. The landlubbers went along to pull in the nets from the shore. There, near the graves outside the village of Kursi, lived the possessed man.

The piers of Capernaum

It was spring, Marcus says, after John the Baptist was beheaded by Herod Antipas. We gathered on the other side of the lake and ate bread and fish in the green grass. It was around Easter, John specifies. They wanted to make Jesus king, but he refused. He walked away.

We sailed back to Capernaum without him, Marcus continues. It was already night. The wind grew stronger and stronger, the waves higher and higher. The light of the moon and stars was obscured. We rowed as if our lives depended on it, but we hardly made any headway. Then he stood there in the middle of the water. But he did not walk straight toward us; it seemed more as if he was walking past us toward a point ahead of the bow. "A ghost is walking on the water," someone cried. There was shouting and panic. Then he said,

"Stay calm, it is I! Do not be afraid."

Peter had stepped overboard, says Matthew, but he had no faith and would have drowned if Jesus had not grabbed his hand.

Mark is enthusiastic: Jesus came aboard and the wind died down!

We wanted to take him aboard, John corrects him. But then we noticed that we had already arrived in Capernaum.

Luke is silent about it.

The piers of Capernaum jutted straight out into the lake, says Mendel Nun. The boat could have been wrecked in that storm. Is that why Jesus couldn't walk straight to the boat?

It doesn't matter, says Matthew, the story of the boat in the storm is the story of our people today.

The naked fisherman

John tells that they were fishing and saw a man standing on the shore of the lake. "Cast your net on the other side," he called. There was a school of fish. "It is the Lord," someone cried. Peter wrapped his cloak around himself and jumped into the water.

Why did he put on his outer garment, you ask, won't it get wet? Don't you mean that he pulled up his coat when he stepped overboard? Some modern translators interpret it that way. Surely that must be what he meant?

No, he was naked, writes John. And a fisherman nods. Weights attached to the edge of the net cause it to descend like a parachute over a school of fish, explains Mendel Nun. He has found countless weights around the lake. One fisherman, Peter, had to dive down to the bottom each time to close the net from below. And yes, you did that naked. But they would never go ashore naked. The point is that Peter did not want to wait until the boat came ashore to meet his Lord. He preferred wet clothes.

John Mark

The puzzle of Mark's life is difficult to piece together: we only have a few pieces, and even those pieces are uncertain. In the letters of Paul and Peter, we encounter the name Marcus in the story of the sixties. In I Peter, the writer calls Mark "my son" and Mark sends greetings to the followers of Jesus in Asia Minor. He is referred to as Paul's "co-worker" and "Barnabas' cousin" in the letters to Philemon and Colossians. His journey to Colossae in Asia Minor is announced there. In II Timothy, he is asked to be brought from Ephesus to Paul and Luke in Rome.

In the book of Acts, John Mark (a Jewish and Roman name) is the son of Mary, the wealthy woman in Jerusalem where the church gathered when Peter was released from prison in the early 40s. Luke recounts that around that time, the young Mark was taken by Barnabas and Paul to Antioch and then to Cyprus; a few years later, he visited the island again with Barnabas. After that, the sources are silent.

Later church fathers report that Mark was in Rome with Peter in the year 42 (which would have been immediately after his first visit to Cyprus) and left for Alexandria around the year 49. In the year 62, he is said to have been succeeded as "bishop" by Anianus. It is also said that he returned around 68 and died a martyr's death. Tradition is divided as to whether he wrote his gospel before or after his visit to Alexandria. Morton Smith, a prominent Bible scholar, even claimed to have found an ancient source from Alexandria that mentions a 'secret,' longer version of the Gospel according to Mark. But others believe that Smith, who has since died, invented this source himself.

The Gospel According to Mark

Scholars say that we cannot say with certainty whether Marcus wrote this gospel, and that is true. The names of the evangelists were added later. And the story does not seem to have taken its current form all at once. While parts of it, such as the Passion narrative, took shape in the 40s, it was not put on paper in two or more editions until the 50s and 60s. But we can see that these stories go back to the Aramaic stories of Galilean fishermen. They took shape in Greek as proverbs and anecdotes. We also know that few people were educated enough to write them down in Greek and turn them into a coherent whole.

We are looking for someone from the second generation who converted the Aramaic of the fishermen into the Greek of new followers of Jesus around the Mediterranean. He or she does not need to have been there themselves, but must have had the knowledge, credibility, and language skills to write this story in such a way that other followers of Jesus could adopt it.

We are looking for someone who, when thinking of Simon of Cyrene, who carried Jesus' cross, does not think of someone from the distant past, but of the father of Alexander and Rufus, whom his first readers also know—possibly the Rufus we encounter with his mother in Rome in the 50s. An international family with Jewish, Greek, and Roman names, in which our writer feels at home. We are looking for someone like John Mark.

The narrator

Mark has a smooth pen. He knows how to string together loose anecdotes like sandwich fillings, and he is not afraid to leave material out. As the director Alfred Hitchcock said in 1966: "Making a film means, first of all, to tell a story. That story can be an improbable one, but it should never be banal. It must be dramatic and human. What is drama, after all, but life with the dull bits cut out?"

If you're not a fisherman, if you don't know when the fish gather and the sardines spawn, when the grass turns green and when winter falls, then you might think that Marcus's entire story covers only a few months. But anyone familiar with the seasons knows that after John's arrest, it takes another two years before Jesus is crucified.

Read it through in one go, or listen to someone read it aloud in a vivid way. Some people have staged Marcus as a play, without changing the text. The story has a natural form: there is a hopeful but confusing beginning with John the Baptist, a crisis in the middle, and an ending in which Jesus is crucified. The turning point of the story is the transfiguration of Jesus in the mountains near Caesarea Philippi, when he is furthest from Jerusalem and struggling with his calling. "You are my beloved child," God's voice says. Jesus is thus recognized three times as God's son: at his baptism, there in the mountains of Caesarea Philippi, and at his death—but the last time from the mouth of the centurion who saw him breathe his last breath.

Mark thus sets the tone for the later accounts of Jesus. His three-part structure forms the heart of the five-part structures of Matthew and Luke. They add the birth and resurrection stories; they also weave a large number of Jesus' sayings into Mark's stories.

The first gospel

Most researchers assume that the Gospel according to Mark is our oldest gospel and that it took its current form around the year 70, after which it was used by Matthew and Luke, among others. It is questionable whether there were earlier versions and therefore multiple authors (Luke may have based his work on a shorter version than Matthew). At the same time, there are biblical scholars who point out that many of the stories themselves took shape in Aramaic in the 40s. Entire passages still breathe the stories of fishermen. Jesus' oral teachings did not necessarily have to be written down. The expectations of the end times are described with the image of Caligula, a "lawless abomination," in mind and not yet from the realization that the temple had already been destroyed.

Listen also to what he says about spirits. For Mark, these are not ghosts, but mainly diseases and sick thoughts that control people and move through the air. That is the Aramaic way of looking at things. They took into account the danger of contagion, which the Greeks did not believe in.

Marcus became the basis for Matthew and Luke to write their stories, while they removed errors from Marcus's not always smooth Greek, caused by the underlying Aramaic. They also deleted his references to "Herodians," who no longer played a role in Israel at that time.

Note about the Herodians: this political group argued that Antipas, the son of Herod who at that time ruled only over Galilee, should rule over all Israel by the grace of God. On his coins, he already called himself Herod. The Herodian movement lost its relevance after his banishment in the year 39. King Agrippa, who ruled until the year 44, had older royal blood and did not call himself Herod on his coins; he called himself Agrippa the Great King.

Shock and horror

This Gospel is also early in theological terms. The question of the suffering of the anointed one is still painfully raised. There is also a constant tension in the story between Jesus as a human being and as the Son of God. Jesus is the son of God without any mention of a virgin birth. In fact, in Mark 3, his mother and brothers say that he is out of his mind when he comes home late for dinner again.

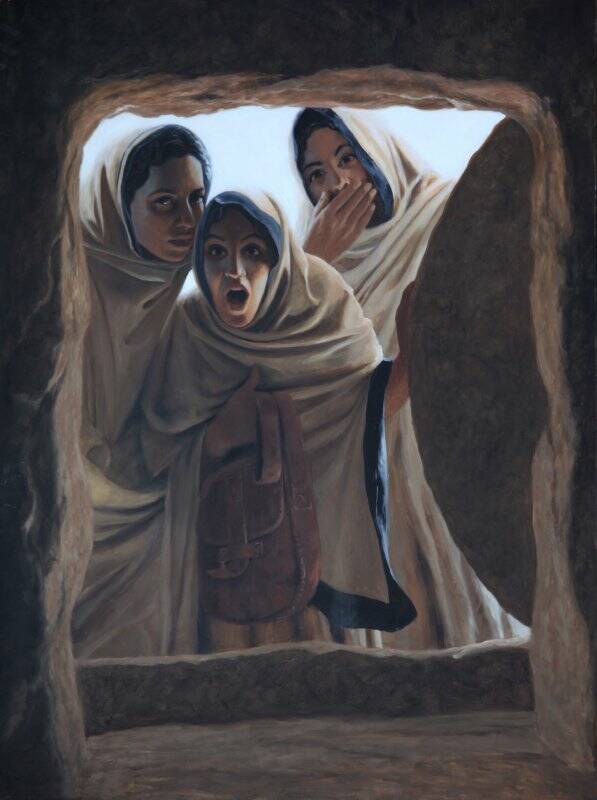

It is a gospel without the risen Lord appearing, without a mission command, and without the ascension. The bewildered women who come to embalm his body hear only these words:

"Do not be amazed; you are looking for Jesus of Nazareth, who was crucified. He has risen. He is not here; see the place where they laid him. But go, tell his disciples and Peter that he is going before you to Galilee; there you will see him, as he told you."

They hurried out and fled from the tomb, for terror and amazement had seized them. They said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid.

The women at the tomb. © Balage Balogh, Archaeology Illustrated.

Later versions sought to improve this abrupt ending (and, given the passage of time, perhaps they had to), but I think it is wonderful that some manuscripts have preserved this first version. The first readers and listeners are still referred here to the witnesses who are still alive. Go to Galilee. Look for them. Talk to them. Let them tell you about their experiences with the living Lord. Then you will understand how the Gospel was read to Mark in the first decades after Jesus' death. Not in place of living memories or passed-down sayings, but as the framework in which those individual memories took on even more meaning. You don't have to read Mark as the direct account of an eyewitness, but it was written and read in the presence of people who had already heard about Jesus before he was crucified. Realize that Jesus' impact on them was so great that they could share such stories about him with each other.

For readers today, like us, that ancient ending may be an invitation to go back to the beginning of the Gospel, to Jesus in Galilee, and to hear his words anew in the light of the resurrection. Then you read the story with different eyes. From the retrospective of the resurrection, you meet him as he is now.

Summary: A Fisherman's Tale, 40s, 50s and 60s CE.

After Caligula's death, the new emperor Claudius made his Jewish friend Agrippa king of all Israel. Agrippa then persecuted the followers of Jesus. Peter is said to have fled to Rome in the year 42, accompanied by the multilingual teenager John Mark, who would later travel around Asia Minor and Alexandria. Mark is said to have translated Peter's fishing stories into Greek and perhaps also into Latin. Later, Jews were expelled from Rome because of trouble surrounding a certain "Chrestus," and we encounter followers of Peter in Corinth. Someone like Mark may have begun to put those fishing stories on paper so that people could continue to share them even without Peter.

- The Gospel of Mark is the oldest continuous gospel story, but it does not yet include the Christmas story or the resurrection stories. It ends with the empty tomb on Easter morning. Many separate stories and the passion narrative took shape in the 40s, and the whole was read aloud in one or two editions at church meetings in the 50s and 60s. We find unique details in it that go back directly to Galilean fishermen like Peter. We hear about Jesus' questions, his family's resistance, and the disciples' lack of understanding. The turning point comes in the mountains of Lebanon, when he has fled because of the beheading of John the Baptist. There, in the dead of night, Peter and John, among others, "see" him talking with Moses and Elijah. It is a mystical experience that puts him back on the road to Jerusalem, where he will confront the rulers with the message of God's kingship. He increasingly accepts that he will die in Jerusalem as the Passover lamb of the new covenant. This Gospel is primarily about the question of who Jesus is as a human being and as the Son of God.

Fisherman on the Sea of Galilee. © Balage Balogh, Archaeology Illustrated.

A bit of background information: Did Jesus really exist?

The problem is that virtually everything we know about Jesus comes to us in the words of his followers, who saw him as the savior sent by God. Theologians and historians therefore distinguish between the historical Jesus and the proclaimed Jesus. The proclaimed Jesus, the son of God, the Messiah, can only be known through faith. The historical Jesus, the man from Nazareth, is the human life that can be reconstructed on the basis of historical research, regardless of the beliefs of the historian. Miracles and a physical resurrection belong to the proclaimed Jesus. By definition, they fall outside the scope of research into the historical Jesus. However, a reputation as a miraculous healer and the testimonies of resurrection experiences by his followers do belong there.

There are two ways of conducting historical research. The first, historical-critical research, goes back from the sources (especially the first three Gospels) to Jesus: what can we say with a reasonable degree of certainty that he said and did? And then, of course, you give priority to things that the evangelists say that do not fit in with their agenda, or that of the early church. That criterion, by definition, produces a distorted picture. And if you are strict, you are left with very little, because what can you really know for sure?

According to E.P. Sanders, The Historical Figure of Jesus (1993), historians agree on the following: Jesus was born during the time of Herod and grew up in Nazareth. He was baptized by John, gathered disciples, and preached the "Kingdom of God" in the villages of Galilee. Around the year 30, he went to Jerusalem at Easter, caused a commotion in the temple, celebrated a last meal with his disciples, and was arrested. He was interrogated by the high priest and then crucified on the orders of the Roman governor Pilate. His disciples initially fled but later experienced him as alive and concluded that he would return as king. In anticipation of this, they formed a community that proclaimed him as God's anointed one.

The second method, which I use in my Psychological Analyses and the Historical Jesus (2011), works the other way around: what kind of historical Jesus do you need to explain his impact on the sources (especially the oldest letters)? This approach uses a historically and critically tested core, but supplements it with less certain elements until a satisfactory and credible explanation emerges for what we can observe in the narrators and translators. A good explanation explains what we read in their writings with as few assumptions from outside the sources as possible.

These are also questions you can ask yourself while reading the New Testament. What impact do you think Jesus had on the people who told about him and translated his message? What kind of person do you imagine Jesus to be in order to explain that impact on them?

Add comment

Comments