Jerusalem and Antioch, 40s CE

Introducing I and II Thessalonians

"Greet Rufus, chosen in the Lord, and his mother—who also became mine," Saul would later write in his letter to the Romans. He writes under the name Paul, perhaps the name of the Roman family from Asia Minor in which his enslaved grandfather or father regained his freedom.

Rufus is also a Roman name: "red (haired)." Is he the Rufus whom the first readers of the Gospel according to Mark knew as the brother of Alexander and the son of Simon from Cyrene in North Africa, the man who had to carry the cross of the broken Jesus before him?

With Rufus and his mother, the words of Jesus entered the world of Jewish migrants in the Greco-Roman world around the Mediterranean. With them, a confused young man found peace. With them, he was allowed to be Jewish, Greek, and Roman. Saul and Saulos, Paulos and Paulus. According to tradition, he was the child of freed slaves and—ironically—precisely because of that, a free-born citizen of Rome. Where others were separated by those identities, he was torn apart by them. Precisely because of that, the unity he experienced here was an experience of unprecedented "freedom in Christ."

There were more people like Saul in Antioch. Joseph Barnabas came from Cyprus. Lucius, another Roman name, came from Cyrene. They called a certain Simeon by his Roman nickname Niger (the black one), perhaps from his time in the legions. Menachem, Manaen to the Greeks, had grown up with Herod Antipas. Complex life stories. Brothers and sisters who helped each other walk the path of Jesus. They were called prophets and teachers. Teachers because they knew the Hebrew Bible and the Way of Jesus. Prophets because in their togetherness they experienced the spirit of Jesus: people saw visions, gained new insights, spoke in tongues, and were healed. Inspired and talented people who made a decision that would change the world.

A decision that was born in the shadow of Caligula.

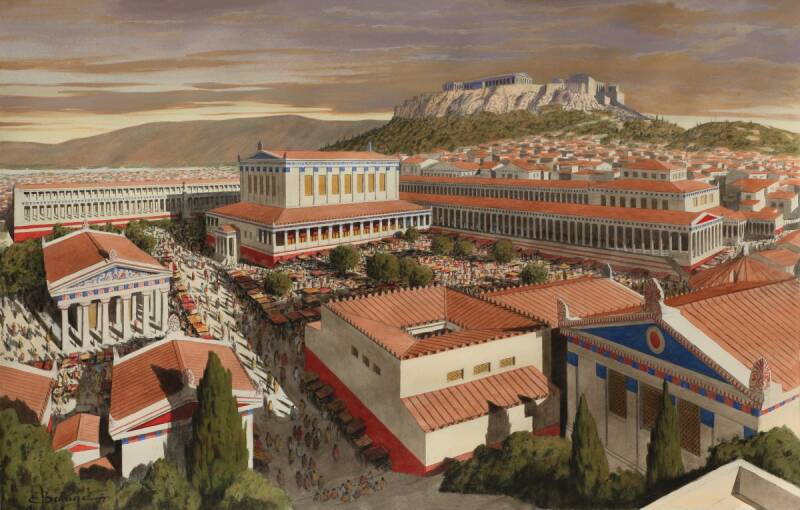

Antioch, the third city of the Roman Empire and seat of the Roman governor of Syria, who was ordered by Emperor Caligula to erect a statue of himself as supreme god. © Balage Balogh, Archaeology Illustrated.

Caligula

Caligula was emperor from March 16, 37, until his death on January 24, 41. The Romans would come to deeply regret his reign: from celebrated son of a god to degenerate sex maniac and international laughing stock. The senators were most ashamed that Caligula took their flattery seriously and forced them to actually worship him as a god.

For the Jews, his reign was traumatic. For the followers of Jesus, it was doubly so. Riots broke out in Alexandria in the year 38, when schemers placed statues and altars for their imperial "god" in Jewish synagogues. Weeks of violence, torture, and looting followed, during which the numerous Jews were locked up in an overcrowded ghetto. In the year 39, the unrest spread to Judea. Caligula sent a new governor to Antioch with a gruesome assignment. In the winter of 39/40, he brought two legions to Judea to quell the unrest and to place a giant statue of Caligula as supreme god in the Holy of Holies of the temple in Jerusalem.

But the Galileans blocked the roads with their bodies, kneeling with their necks exposed. "Better death than this abomination in the temple," they said. The farmers stopped farming, threatening famine throughout Syria. The governor relented. He had the sculptors work slowly and sent a request to the emperor. Then the hooligans of Antioch set fire to the synagogues there as well.

The answer was slow in coming. That summer, Caligula traveled to the Low Countries at the mouth of the Rhine. He wanted the legions along the Rhine to conquer Britain.

The face of Emperor Caligula, reconstructed by Daniel Voshart.

The horror that brings destruction

Jesus' followers are torn between fear for Jerusalem and longing for the coming of their Lord. In the shadow of Caligula, they remind each other of his words and search the Jewish holy books for God's plan.

Someone says: Do you remember how we sat on the Mount of Olives and looked out over the Temple Mount? How the temple glistened in the sun? What he said then?

He said: Do you see these great buildings? Not one stone will be left upon another that will not be torn down. There will be wars, and famine, and pestilence. And yet that is only the beginning.

Daniel wrote: After the death of the Messiah, the people of a foreign king will come and destroy the city and the temple. He will bring an Abomination that causes desolation, a Lawlessness that destroys.

Daniel wrote: His armies will occupy and desecrate the temple and the fortress. They will place there the Abomination that causes desolation, a Lawlessness that destroys. That king will do as he pleases, he will exalt himself above every god and speak terrible words against the Most High.

Daniel wrote: Then Michael, the great prince who stands before the children of God's people, will arise. Just when the distress is greater than ever before in human history, the people will be delivered. The dead will rise and the righteous will shine like stars in the sky.

Did not Jesus say: With the voice of the archangel and the trumpet of God, the Lord himself will descend from heaven and gather the children of God, the dead and the living?

There were sufficient points of reference in John the Baptist's and Jesus' proclamation of the kingdom of God to interpret Caligula's actions as the last convulsions of evil in view of the coming of the heavenly Lord. There were also enough similarities between Caligula's plans and the prophecies of Daniel to relate them to Jesus. With this, I suspect, Caligula unwittingly gave a huge impetus to the development of ideas about an "end of time" among the followers of Jesus, culminating 50 years later in the book of Revelation.

The end that did not come

But things would turn out differently. On January 24 of the year 41, Caligula died, and three weeks later the news reached a relieved governor of Syria. The legions returned to their army camps. The gruesome image was never placed in the temple in Jerusalem. There was no Jewish uprising, and Jerusalem was not destroyed.

And Jesus did not return.

What does God want?

What do you do when the most important prophecy that your community lives by does not come true? Some give up, others dig deeper: The prophecy has not yet come true. The prophecy is correct, but we have not understood it properly. Did Jesus not say, "All nations must hear the good news"?

Did he not say, "First they must hear"?

Jesus' friends in Antioch look it up in the scroll of the prophet Isaiah. How the cut-off stump of David's family would sprout again and its root would bear fruit again. How the anointed one would stand as a banner under which all nations would gather. How the Spirit of the Lord would rest on that anointed one. And how the wolf and the lamb would lie down together on God's Holy Mountain. They read that his deeds must be made known among the nations. The gospel is no longer about another king for Israel alone, it is about another emperor, a supreme king.

Filled with the Holy Spirit, they lay their hands on Barnabas and Saul. The next day they leave. First Cyprus, then Galatia, and then to the West.

To the wolves.

The first letter to the Thessalonians

The oldest text in the New Testament is addressed some five or six years later to the brand-new followers of Jesus in the city of Thessalonica, written by a concerned Paul, together with Silvanus and Timothy.

Silvanus is also a man with a double or triple identity. He had come to Antioch on behalf of Jesus' followers in Jerusalem to build a bridge between the Aramaic world and the Greco-Roman world. In Aramaic he is called Silas, in Greek he is called Silvanus, although that is a Roman name. Paul and Silvanus revisited the churches in Galatia and took the teenager Timothy with them, who was also the son of a Jewish mother and a Greek man. They crossed over to Europe and brought the gospel to the Roman colony of Philippi.

The market of Athens, the cultural capital of Greece (now overshadowed by commercial Corinth). © Balage Balogh, Archaeology Illustrated.

As soon as Timothy returns and is able to reassure them, they write this letter, probably from Corinth. It is to be read aloud in the congregation, so that everyone can hear it as if Paul, Silvanus, and Timothy were present in person. It is a letter that focuses on faith, hope, love, and the hope of union with Jesus in God's heavenly kingdom. In the letter, they record their memories in order to protect their reputation and, with it, the reputation of their message. They ask their friends to support each other and their new leaders and to know that they are part of a worldwide movement.

The Second Letter to the Thessalonians

The second letter seems to have been written as a correction to the first. Apparently, the message of faith, hope, and love in anticipation of the Second Coming is not good for everyone. Some sit back and forget their own responsibility. They are fine with the rest taking care of them. Why work or save when Jesus will soon come to take you to the heavenly kingdom? They chase every rumor and retreat into pious selfishness, waiting for the end. The letter warns them: "Don't immediately lose your mind and panic!"

The letter is so different in tone and in its perception of the end times that many theologians believe it cannot have been written by Paul himself. They assume that the letter is a somewhat later correction to the message of 1 Thessalonians. On the other hand, the letter cannot be too late. It is precisely in this letter that it becomes clear how strongly Caligula's horrific plans still overshadow the young church:

[The 'day of the Lord' will only come when] the lawless abomination is revealed, the son of destruction. He is the one who will set himself up against and above everything that is called divine or is so revered. He will take his seat in the temple of God and present himself as if he were God.

The expectation that the Roman emperor would herald the end by placing his image in the temple in Jerusalem would disappear with the destruction of Jerusalem in the year 70. We still see this idea in the early Gospel of Mark, and it goes back to the Aramaic-speaking friends of Jesus. The Greek of 2 Thessalonians 2:3 (the words for "lawlessness" and "destruction") and Mark 13:14 (the words for "abomination" and "destruction") may be different, but the words go back to the same synonyms in Hebrew and Aramaic for destructive idols and altars.

Written directly by Paul or shortly after him, 2 Thessalonians is best read from the perspective that Paul, Silvanus, and Timothy, who had meanwhile encountered other followers of Jesus in Corinth, were themselves corrected: be careful with that proclamation of an imminent end time. See how that can lead to fanatical or apathetic behavior. Bring the gospel to all people, but maintain a healthy balance between longing for the coming of the kingdom of God and walking the Way of Jesus in the here and now.

Summary: In the shadow of Caligula, 40s CE

A handful of years later, the time seems to have come. The Roman emperor Caligula demands that the Jews worship a statue of him as God in the temple in Jerusalem. The people beg the Syrian governor in Antioch not to do so. The harvest is rotting in the fertile fields of Galilee. Jesus' followers gather in prayer: Maranatha. And then comes the news that the emperor has been assassinated and that the statue will not be erected. Joy, but also confusion: Will Jesus not return? Have they misunderstood God's plan? Jesus' followers look it up in the Jewish Bible. They read it in the prophet Isaiah: first, the gospel must be brought to all nations. The Second Coming becomes even more important! The Lord is coming not only for the Jews in Israel, but for his children (Jews and non-Jews) among all nations. Jesus' followers in the Syrian capital of Antioch send Barnabas and Paul as emissaries to the cities around the Mediterranean, where their controversial preaching, accompanied by "power and the Holy Spirit," convinces some people and angers others.

- The oldest piece of the New Testament was written in the late 40s: the First Letter to the Thessalonians. We are immediately thrown into the thick of the action. After the necessary commotion in the cities of Philippi and Thessalonica in the late 40s, Paul, Silas, and Timothy arrive in the large Greek port city of Corinth. They send a letter full of faith, hope, and love back to the church in Thessalonica: Hold on, the Lord is coming soon.

- II Thessalonians can be seen as a correction to the first letter, which was misunderstood by some: waiting for the Lord does not mean that you have nothing to do now!

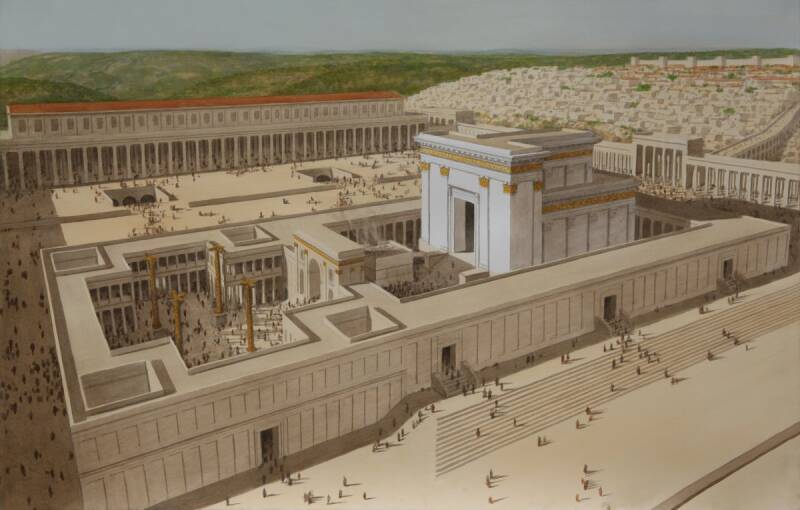

The sanctuary on the temple square in Jerusalem. © Balage Balogh, Archaeology Illustrated.

A bit of background information: Pseudepigraphical letters from Paul?

Pseudonymous letters are letters written under a false name; pseudepigraphical letters are letters written under a real name but falsely attributed to that person. Theologians view the letters in which "Paul" is named as the sender as follows:

- Undisputedly from Paul: Romans, I and II Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, I Thessalonians, and Philemon, a total of 61 chapters out of 87.

- Letters from the first century attributed to Paul, written by him or his disciples: Ephesians, Colossians, and II Thessalonians, 13 chapters out of 87.

- Pastoral letters, considered by many to be pseudepigraphs and written only at the beginning of the second century: I and II Timothy and Titus, also 13 chapters out of 87.

To understand Paul's controversial life, the undisputed letters naturally take precedence, although you still have to bear in mind (especially with Paul) that you are only reading one side of the story.

The disputed letters are often read as the words of his followers at a later date, attributed to Paul and distributed as such. This is not without its problems, however. Although writing letters, acts, gospels, and revelations in the name of the apostles became a literary form in the second century, it seems that in the first century, people would simply regard a letter in Paul's name (without his input) as a forgery. It is not without reason that II Thessalonians 2:2 warns against forgeries and 3:17 clearly claims that the letter was written by Paul himself. The older the letter, the greater the moral problem of pseudepigraphical letters.

The fact that many letters were already being circulated as authoritative during the first century shows, first of all, that many people early on and quite generally regarded them as authentic letters from Paul. This is less true of the pastoral letters, however, because they were not included in the collection of letters until the second century.

Unfortunately, it is quite difficult to determine where and when to place a pseudepigraphical letter. There are always several possibilities. In this book, I choose to give priority to the presentation in the text itself. If the letter claims to be from Paul, then we also read it during his lifetime. I do indicate any doubts about the authorship. But even a literary creation, such as a letter attributed to an apostle, is only of any quality if it actually fits into the time in which it is thought to have been written. Early Christians accepted these letters because they fit so well into the story of Paul that these early readers thought they were actually written by Paul himself.

The story that emerges is therefore surprisingly coherent.

Add comment

Comments