Ephesus, late 90s

Introducing: John, I, II and III John

Despite the humiliation, torture, and sometimes even executions, more and more people joined Jesus' followers. A mixed group emerged: Jewish and non-Jewish inhabitants of Asia and migrants, including quite a few Jewish refugees from the war of 66-73. Many became leaders in the communities of Asia. We hear of John (Yochanan in Hebrew) of Patmos, John the Elder, and John the Apostle, who died around the year 100 as the last of the twelve apostles. Then there is Aristion, to whom someone later attributed the ending added to the Gospel of Mark. The daughters of Philip, all prophetesses, are said to have moved from Caesarea to Hierapolis near Laodicea. According to many later sources, they were called Hermione, Eutychis, Irais, and Chariline.

In this diverse and rapidly growing movement, not everyone was preoccupied with the end of time. Many people simply did their best to be there for each other, to follow the way of Jesus, and to contribute to their faith community. People learned and taught, read and copied, discussed and corrected. Sometimes something new was even written that would completely change our view of God.

Like these three words: "God is love."

The "school of John"

John did not attend school in Ephesus. However, it is striking that after the Jewish war in Ephesus, a new language was used to speak about Jesus, God, and the Holy Spirit. We see this not only in the Revelation of John but especially in the Gospel of John and the letters I, II, and III John. And because we do not believe that one and the same person wrote all these words, we speak of the "school of John."

They use a limited but extremely effective vocabulary that expresses divine glory, closeness, and unity. Think, for example, of the Lamb who bears the sins of the world, of the bride and the bridegroom, and of Jesus' "I am" statements: the alpha and the omega, the beginning and the end, the word of God, the light, the living water, the truth, and so on. See the emphasis on the unity of the Father and the Son and all of God's children, the Holy Spirit as comforter, eternal life as knowing God, God's love for the world, and the one commandment of love.

Are these not words that have deeply influenced our view of God and the gospel?

The writers, their roles and their writings

It cannot be said with certainty who wrote the Gospel and these letters. But that does not mean that readers did not get an impression of the implicit author(s). In the Gospel according to John, a Witness of the separate stories, a Compiler of the Gospel, and a Final Editor emerge who use the same words as the authors of the various letters.

- The Witness. The separate episodes are told in retrospect by the disciples. Several times, the Witness remarks how they only understood what they had experienced with Jesus in retrospect. In various places, we encounter the "disciple whom Jesus loved": at the Last Supper, at the cross, and at the empty tomb. His role as Witness is revealed in the closing words added by the Final Editor:

- Gospel of John 21:24 "This is the disciple who testifies to these things and who wrote them down. We know that his testimony is true."

- The Compiler. Next, there is the role of the Compiler, who reveals himself and his implicit readers/listeners in the preface and the first closing words:

- The Gospel of John 1:1 "In the beginning was the Word, ... 14 And the Word became flesh and dwelt among us, and we beheld His glory..."

- The Gospel of John 20:30 "Jesus did many other things in the presence of his disciples that are not written in this book. 31 But these are written so that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that by believing you may have life in his name."

The compiler is therefore also a witness. It could be the same person or another disciple of Jesus who also came to Ephesus and was involved in the writing process. In any case, he presents himself with almost the same words as the writer of 1 John:

-

- The First letter of John 1:1 That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we have looked upon and touched with our hands, concerning the Word of life...

- The First letter of John 5:13 These things I have written to you so that you may know that you have eternal life, you who believe in the name of the Son of God.

- The Final Editor. Finally, there is the Final Editor, the character who writes the second closing words and is responsible for the final version of the Gospel according to John. He uses the same words as the writer of the short letters II and III John, who introduces himself as the "Elder":

- The Gospel of John 21:24 "This is the disciple who testifies to these things and has written them down; and we know that his testimony is true."

- The Third Letter of John 12 "...we also testify; and you know that our testimony is true."

In III John, the testimony concerns the reliability of a certain Demetrius. The readers of the letter can trust the testimony about Demetrius because they know the Elder to be reliable. Similarly, they can trust the reissued Gospel because the Final Editor considers the beloved disciple to be reliable. The role of Final Editor must therefore be fulfilled by a character other than the Witness.

The Witness and the differences with Mark, Matthew, and Luke

The first thing that strikes us is that the Gospel of John contains only a few stories, sometimes with abrupt transitions. They are much longer than the short stories in the previous three Gospels. A good example is the story of the miraculous feeding in chapter 6. The first 21 verses follow the same sequence as Mark, Matthew, and Luke. But then it continues for another 50 verses in the form of a speech by Jesus, debates with opponents, and the impact on the disciples. An event from the life of Jesus is thus expanded into a sermon in story form.

The second difference is that Jesus speaks freely, while the other Gospels combine existing one-liners and parables into a larger whole. This gives the end result something unnatural, as if the text has been condensed. In Luke, you see this effect when you compare Jesus' words with the much freer speeches of others in Acts. John is much less cautious with Jesus' words and is not afraid to incorporate current issues from his own time, such as the tension with the synagogues. He also explicitly states that the Holy Spirit will continue to speak Jesus' words to believers after his departure. Moreover, Jesus speaks in the vocabulary of the "school of John," which is best seen when you compare it with a letter such as 1 John. This style of speech is only occasionally found in the other Gospels (e.g., Luke 10:22).

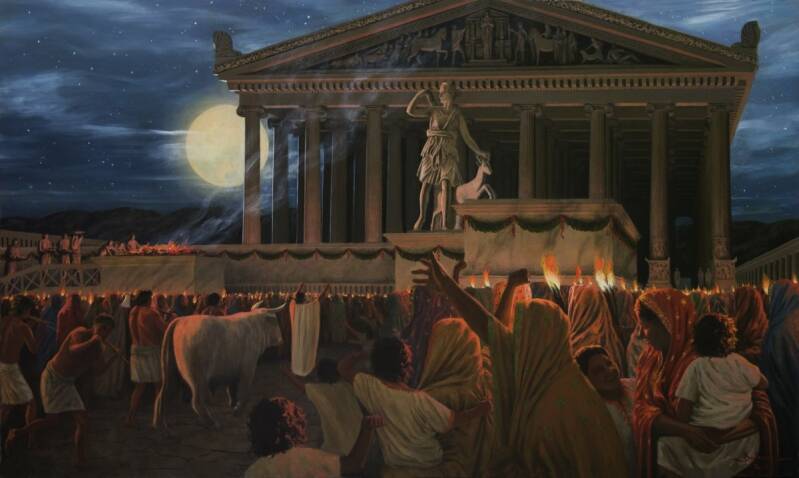

Ephesus, festival in the Temple of Artemis, one of the Seven Wonders of the World © Balage Balogh, Archaeology Illustrated.

A third difference is the emphasis on Jerusalem. Mark summarizes the story of Jesus in three steps: the beginning in Galilee, the transfiguration in the mountains, and the end in Jerusalem. Matthew and Luke adopt this as the core and backbone of their story. The Gospel of John, on the other hand, mainly contains stories that take place in Jerusalem during the various Jewish festivals when Jesus visited the city and its temple. Was this because his readers already had access to the other Gospels? Was it because the writer originally came from Jerusalem? Or was he mainly active in cities such as Jerusalem and Ephesus after Jesus' crucifixion and did he select stories that appealed to his audience there?

Finally, it is striking that there is no list of disciples or of the Twelve. A few of them are mentioned more often, such as Peter, Andrew, Philip, Nathanael, Judas, and Thomas, but usually no distinction is made. And then there is one disciple who was close to Jesus and Peter but whose name remains unmentioned: the "disciple whom Jesus loved."

The Compiler and the Final Editor

We may conclude that the Witness's stories were edited, first by the Compiler and then by the Final Editor. In these roles, they had to select, arrange, and edit the material.

The story of the cleansing of the temple and the conversation with Nicodemus (2:13-3:36) may have been brought forward in time; the other Gospels place the cleansing of the temple shortly before the crucifixion. Now it gives a kind of "proposition" at the beginning: "For God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life."

Without the "farewell discourse" in chapters 14 through 17, the story of the Last Supper is more similar to that of the other Gospels, and we see that in later reuses of this framework (questions and teaching), the disciples' questions are mainly addressed to the risen Lord. Sometimes it seems as if several versions of the same material have been combined here. For example, Jesus complains that no one asks where he is going (16:5), while Peter had indeed done so earlier in the conversation (13:36). It seems as if a third person has cautiously tried to merge the words of the Witness rather than writing a new version himself.

Was the apostle John the Witness?

Not as the official report of an eyewitness, but as the testimony of the disciple who loved Jesus so deeply even after his death and translated his message so well into the stories he told people.In the final story, the Editor-in-Chief reveals that the "beloved disciple" is the Witness. This disciple is even closer to Jesus than the others. He lies at his side during the Last Supper. He is the only disciple standing at the cross with the three Marys and Mary's sister. The dying Jesus connects his mother Mary with him as if they were mother and son, and from that moment on she comes to live with him. When Mary Magdalene finds Jesus' tomb empty on Easter morning, she rushes back to him and Peter, and he runs to the tomb faster than Peter. At the end, we see both of them again fishing on the Sea of Tiberias, where the Witness is the first to recognize the Lord calling to them from the shore.

The Witness also breaks through occasionally to comment in retrospect, as at the entry into Jerusalem: "His disciples did not understand this at first, but only later, when Jesus was exalted." So even then, the beloved disciple belonged to this group.

Traditionally, the church has identified the beloved disciple with the youngest apostle John (at least since the Church Father Irenaeus, who was born in Smyrna around the year 125). After all, he was one of Jesus' three most trusted disciples, along with his brother James and Peter. It was and is recognized that this was a completely different gospel with different events and a different writing style. They called it a "spiritual gospel."

Jesus' first disciples did not come out of nowhere. They were probably friends and cousins who also followed John the Baptist. The brothers James and John are mentioned as the sons of Zebedee and Salome, who may have been Mary's sister. They would have spent a lot of time together when both families lived in Capernaum (John 6:42). It is quite possible that Salome and her son John were standing at the cross when Jesus' adult disciples fled. In that case, it makes sense that Mary first came to live with them after her husband and then her eldest son had died.

But more important for those who accept John as the Witness is this consideration: How could someone in the first century be so free with the words of Jesus when the authors of Mark, Matthew, and Luke did not dare to do so? And why, despite that freedom, did an editor-in-chief treat the words of the Witness so cautiously? How could a gospel that was so different be accepted so quickly and widely in the churches? Why couldn't the Church Fathers simply reject this gospel as a forgery when it was so enthusiastically used by "heretics" in the name of John? Why all this, unless John had somehow been involved in its creation?

Other theologians, and they are in the majority, have great difficulty with this: a cousin and close friend of Jesus as the author of a gospel. "How could a Galilean fisherman write such a thing?" But John was a teenager when he began to follow Jesus. In the thirty years that followed, he emerged as a "pillar of the church" in bilingual Jerusalem (Gal 2:9) and then worked in Ephesus for another three decades. This also provides a possible explanation for why he liked to tell stories that fit in with the city of Jerusalem and the temple festivals. They also fit well in the city of Ephesus, where the world-famous temple of Artemis stood. "But how can an eyewitness differ so much from the other evangelists?" That is only a good argument if John had wanted to write a biography of Jesus. Perhaps we should accept that the genre of these stories was really different from that of the synoptic gospels. Early church fathers already pointed out that John's teaching was less about the historical story of Jesus and more about its spiritual interpretation. His teachings were more narrative "sermons," which were only later compiled by others into a "spiritual" gospel.

I sometimes compare them to the dialogues of Plato, who was only 25 when Socrates died. Yet in the decades that followed, he was able to describe many long conversations with his teacher word for word. No one believes that these dialogues accurately reflect what was discussed at the time; Plato dramatizes his own teaching. But why do we still think that Socrates speaks to us through Plato's dialogues? Is it because we suspect that Plato was the disciple who understood Socrates best, even after his death? That is how this gospel wants to be read.

The story of John

Try it. Read these stories as the stories of a young fisherman who loved his older cousin Jesus intensely. Who traveled with him for two years, walking through towns and countryside to show people that they are children of God and brothers and sisters to one another. Who saw his cousin and then his own brother die for that message. Who, after the crucifixion, led a faith community for sixty years that studied the scriptures, where Jews and non-Jews discussed the gospel, the poor were supported, and believers learned who and what Jesus was. Who continued to experience an intimate spiritual connection with Jesus and lived and spoke from that connection. Listen to how he communicates with his brothers and sisters in Jerusalem and later in Ephesus by telling stories from their own urban environment, bringing Jesus back to life through his words and addressing their current problems. See how he does not focus on the twelve apostles or himself by name, but simply on being a disciple of Jesus. How he invites everyone to love one another and to know themselves as beloved disciples of Jesus.

John, fragment of the Fresco of the Good Shepherd, Catacomb of St. Thecla in Rome, 4th century.

Appearance or reality?

Whát is Jesus?

From an early age, John experienced how that question was answered over and over again. In Galilee, he came to the conclusion that Jesus is the promised Christ; in Jerusalem, after the resurrection, he understood that he is the Lord himself who will come from heaven. He witnessed how the gospel spread around the Mediterranean among non-Jews who struggled with the idea of a physical resurrection. We read about them in 1 Corinthians 15 and 16 and in 2 Timothy 2, and we see it again today: it is difficult to believe in a physical resurrection. Surely the spirit is higher than the flesh? Shouldn't you see the resurrection as something spiritual, a kind of awakening, which has already taken place when you come to faith, to enlightenment? Surely God is immaterial, spiritual?

Yes, God is spirit, Paul already answered when those questions were asked in his time; Jesus died in the flesh in order to be the life-giving spirit in us now. But he loves the body that he himself created. We humans are not only spiritual beings, but also psychological and physical; we are not ourselves without our bodies. The spirit does not reject our animated body: it brings it to life. Already now with heart and soul and symbolically in baptism, but soon also when the Lord returns to unite us with God. Of course, material flesh and blood cannot ascend to the immaterial kingdom of God, but God will renew and transform creation and our bodies. Paul then supported his argument with the general stories, recognized even by his opponents, of the appearances of the risen Lord to his disciples.

Now, thirty or forty years later, most followers of Jesus seem to have come to the realization that if Jesus is one with the Father now and forever, he must have been so even before heaven and earth were created. After all, God is eternal and unchanging. The Lord who ascended into heaven therefore first descended into our reality from that heaven. And that also gives those who doubt the physical resurrection new food for thought.

Some, such as Cerinthus in Ephesus, now ask questions such as these: Did not the eternal Son of God, the spiritual Christ, descend upon the man Jesus, the son of Joseph and Mary, at his baptism, as we read in the Gospel according to Mark? Did not this spiritual Christ leave behind the body of the man Jesus on the cross when he breathed his last breath? Surely God cannot suffer? Is it not the eternal, spiritual Christ whom the disciples met as the risen one? And will we not also live on in spiritual form when we leave this body behind? No, say others, with Matthew and Luke in their hands, Jesus is the Christ, in spirit, soul, and body. The son of Mary is the eternal Son of God, his body was conceived by the Holy Spirit in the virgin Mary. You cannot separate his love from the body with which he loved us. He rose physically from the dead. His tomb was empty.

Some ask further: But if his human body was conceived by the Holy Spirit, was it then a fully human body? If we accept that Jesus is the Christ, that the Son of God is the son of Mary, must we not conclude that Jesus' body must have been an immaterial body from the beginning? That his suffering was an illusion? Would the perfect Son of God really defile himself with a perishable fleshly body that digests food and will itself be digested? And don't the stories of the Storyteller show that God is spirit and truth, that the Jesus who speaks in them was not earthly but heavenly, that he came down from God to save us from this corrupt world ruled by Satan? He did not need to become physically human if he did not come to save our bodies, they say. He appeared to us to free our souls from this body and to unite them with God in spirit.

The Compiler wants nothing to do with it. It makes him angry; he considers it lies. The Witness loved Jesus' body, including the hunger and thirst and sickness and hardships on their long journeys together; yes, you even miss his breath in the morning when he no longer wakes up next to you. This disciple saw him suffer and die. He wept when that body was taken down from the cross and laid in the tomb. And he saw the tomb empty.

The thirty-year-old Polycarp, who would later become bishop of nearby Smyrna, is said to have recounted how the old John turned around when he saw Cerinthus in a bathhouse in Ephesus. "Get out of here, for there sits the enemy of truth. If we stay here, the roof will collapse," John is said to have said.

Ephesus, the large bathhouse at the harbor © Balage Balogh, Archaeology Illustrated.

The compiler and writer of 1 John: “The Word became flesh.”

John's stories were compiled into a continuous narrative, with a preface and a conclusion by the Compiler. His aim was to convey John's unique perspective on the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. But he also wanted to prevent the stories of the Narrator from being misread through the lens of Cerinthus. That is why he emphasizes that Jesus is the Christ himself, the Son of God. "The Word became flesh." He could not have said it more bluntly or tangibly. You see this in the prologue and you see it in the appearance of the risen Jesus to the "unbelieving Thomas" with which he concludes the Gospel: "Put your finger here and see my hands; put your hand here and feel [the wound] in my side; do not be unbelieving, but believe." Think of the writer of 1 John: “What we have seen with our eyes, we have felt with our hands.” Blood and water flowed from the wound in Jesus’ side, clear proof of his death. And Thomas responds with a profession of faith: "My Lord and my God!" These were the same words with which Emperor Domitian allowed himself to be addressed at the end of his reign. The same words that the governor of Asia demanded of the Christians when they offered sacrifices to the image of the emperor in order to save their lives.

It is not entirely clear from the text whether the Compiler is the same person as the Witness. He may also be the same person as the Final Editor or a third individual. But it is clear that the Compiler is the same person as the writer of 1 John, as we have seen. It is perhaps the most beautiful and radical letter ever written about God. The letter teaches us that those who love God experience Him, because "God is love." That those who continue to act in love cannot sin—no, not that you will not make mistakes, but they can no longer separate you from God.

But beware. Towards the end of that first century, new errors began to arise: the claims that Jesus was not the same as the Christ or that Jesus Christ did not have a normal body. The writer calls this the doctrine of the "antichrist" because it undermines the essence of his act of love. If his suffering is a sham, then his love is also a sham. No, says the writer, not only was the baptism real, but so was the blood on the cross. The water and the blood and the Spirit all say the same thing: the man Jesus is the Son of God. The love he shows us in his body is the love of God. Apparently, teachers have arisen who now deny that physical suffering. That is why the writer calls on the followers to test their spirits and remain with the Spirit with whom they are "sealed" (possibly a reference to their baptismal promise and anointing) and the proclamation they heard earlier.

The Editor-in-Chief and writer of II and III John: Jesus' suffering was real

Virtually no one doubts the authenticity of III John. It has all the characteristics of a short letter and does not claim to be an authoritative message or to have been written by someone famous. It simply says: "The presbyter," or the Elder. It has been suggested that II John is a later letter modeled on III John, but most theologians see no conclusive evidence for this.

We cannot deduce the name of this Elder from his own words. However, ancient sources mention another John. Papias, who must have been in his thirties when the Gospel of John and these letters were written in or around Ephesus and who became bishop of nearby Hierapolis ten or twenty years later, speaks of two different Johans who passed on the words of the Lord: one was the Apostle and the other the Elder. The Elder is also said to have heard Jesus himself.

Those who listen to the letters hear in them the voice of a shepherd who is concerned about house churches that are threatened by the heresy that Jesus Christ was not born with a real body, crucified, and risen, or that do not offer hospitality to the messengers he sends, such as Demetrius, and do not allow them to warn people against such heresy in their meetings. II and III John are letters that the elder gave to his messengers. In this way, they could speak in his name and stir up the desire to meet him again.

We have already seen that the Final Editor appealed to the reputation of the beloved disciple to emphasize the reliability of the newly published Gospel. He does so again very specifically in a subordinate clause in the story of the crucifixion, just as a soldier has pierced the side of the dead Jesus and water and blood flow out:

John 19:35 And [the beloved disciple] who saw it has testified, and his testimony is true; and he knows that he speaks the truth, so that you also may believe.

The Final Editor is therefore concerned with the same thing as the Elder: he wants to convince readers that Jesus had a real body and had truly suffered.

Read the story in John 21, after the first conclusion, which must have been added by the Editor-in-Chief. It is a fisherman's story with details that only a fisherman could know, one of many stories by John himself that were not selected by the Compiler. But the Editor-in-Chief adds it anyway for two reasons. Firstly, because the deeply grieved Peter, who had denied Jesus, is reinstated as shepherd of Jesus' sheep. Perhaps that was topical. Perhaps there were leaders in Asia who, under pressure from persecution, had denied Jesus and, like Peter, were being reinstated in their office. In addition, there is the prediction about Peter's execution and the fate of the beloved disciple. Many, perhaps even the Editor-in-Chief himself, had fed the expectation that the Lord would return before the death of his last disciple. But that turned out to be incorrect. The beloved disciple died, and the Lord has still not returned. The church must now move forward. But Jesus did not leave them as orphans. They not only have the Holy Spirit to comfort them, but there are also tried and tested shepherds to guide them.

Love remains

"The Word became flesh" and "God is love." You only realize how revolutionary that is when you read the Greek-Roman philosophers who were popular at the time, such as the Stoics. For them, the logos is Reason, the natural law given by God, and that which brings order to the world. They argue that by following the immaterial logos, the highest ratio, people are able to withstand physical suffering. To do so, you had to resist being led by your emotions; apatheia was the solution.

But the word of God, memra in Aramaic, is more than logos. It emphasizes God's compassionate and creative involvement. God reveals himself to people in creation, in the scriptures, and in our hearts. God is love. He is not apathetic; he is not Aristotle's Unmoved Mover. He is personal, involved, and active.

John says "no" to the claim that God cannot suffer or feel, that He has nothing to do with creation or the body. If God is love, then "God" is the deepest thing humans can feel and the greatest thing humans can do for one another. God is the dynamic love of father and son, of bride and groom, and of His Spirit in our spirit. Through that community, we are taken up into love, into that divine unity. God happens.

Eternal life, says John, is not escaping from this world to an immaterial reality. It is knowing God and Jesus Christ, who makes Him known in our physical reality. “No one has ever seen God, but the only begotten God, who is in the bosom of the Father,” as the beloved disciple lay in Jesus’ bosom, “has made Him known.”

Eternal life begins with love.

Summary: "God is Love," 90s

The last books of the New Testament were also written in or around Ephesus. While the Second Coming becomes increasingly important in the visions of some, the Way of Jesus continues to ascend (or move inward) in the eyes of others. A young disciple of Jesus, John, many believe, not only recounts what he remembers of Jesus, but also what the Holy Spirit reveals to him about its meaning: the Father and the Son are one. Jesus is the Way, the Truth, and the Life. Eternal life begins now, if you come to know God through the Son whom He sent. Some believers conclude that the divine Jesus never really became human. Others expect John to live until the Second Coming of the Lord.

- A selection of his stories is compiled in the Gospel of John, with a preface by the same writer as the author of the First Letter of John. He wants to convince his readers that Jesus truly became human: the Word became flesh. In the Son, the Father has become part of our reality, in order to bring us to the Father. Jesus' commandment of love is equivalent to an intimate relationship with God, for "God is Love."

- After the death of the beloved disciple, a final revision of the Gospel follows. In an additional chapter, the editor emphasizes that Jesus never said that John would not die. What matters is that we love Jesus and follow him through death to life. That is the reliable testimony of this beloved disciple. The language used by the final editor is reminiscent of the Second and Third Letters of John. The commandment of love is the secret of those who want to walk with Jesus.

Ephesus, Curetes Street© Balage Balogh, Archaeology Illustrated.

A bit of background information: Jesus' journeys to Jerusalem in John and Luke

Now that we are more familiar with the stories of the four evangelists, we can take another look at Jesus' journeys to Jerusalem in the Gospel of John.

We have come to know Mark as a smooth writer. After an introduction about the baptism, the story jumps to the arrest of John the Baptist. In Galilee, Jesus and his friends continue to spread the message of the Baptist. The fishing stories show that this is in winter. In the spring, when the grass is green, John is beheaded and Jesus retreats to Lebanon, where, near Caesarea Philippi, not far from Mount Hermon, a transformative experience follows, the turning point of the Gospel. Jesus understands that he will die in Jerusalem. Once again, the story jumps forward: around Easter the following year, Jesus and his friends travel to Jerusalem, where he is arrested and crucified. Mark's Gospel is therefore a true story, with a beginning, a turning point, and an end. It is also a selective story. Mark tells us nothing about the period when John reached the whole people with his message, about the time between Jesus' baptism and John's arrest, or about the eight or nine months between the transformation on the mountain and the final journey to Jerusalem.

We also saw that Matthew and Luke maintain Mark's three-part structure, but divide it into five parts by adding the birth stories and resurrection stories. At the same time, they enriched the three parts themselves with more deeds and, above all, more words of Jesus. But Mark's geographical scheme remained intact: a starting point in Galilee, a turning point in the north, and the end in Jerusalem. In Luke, this seems somewhat forced. The geographical references in Luke's long travel account (9:51-19:41) point to different routes and thus different journeys to and from Jerusalem. However, Jesus never arrives there because of the geographical scheme in which the story is told.

We therefore do not need to reject in advance the historical truth or probability of the journeys to Jerusalem in the Gospel of John. In fact, if we read Luke and the Acts critically, there are sufficient points of reference for exploring an underlying historical framework that fits reasonably well with Jesus' journeys in the Gospel of John.

A map of Palestine can be found here.

- Disciples of John. According to Luke 3:1, John the Baptist arose as a prophet in the fifteenth year of the reign of Tiberius (from mid-28 to mid-29). In his time, he baptized "all the people." Acts 13:24-25 indicates that he did not speak about the Messiah until the end of his career (the passage in Luke 3:15-18). Acts 1:21 and John 1:28-41 both suggest that Jesus and his friends were first disciples of John the Baptist for a time, before John the Baptist pointed his disciples to Jesus. This is consistent with the fact that Peter and Andrew still live in Bethsaida in John 1:45, while Peter, after the arrest of John the Baptist, is apparently married and lives with his mother-in-law in Capernaum (Luke 4:38).

- Early activities of Jesus and his friends in Judea. John 3:22 and Luke 4:44 (but not in all manuscripts) both speak of activities of Jesus and some of his friends in Judea. John 2-4 takes place before the arrest of John the Baptist (3:24). We see Jesus at Passover in Jerusalem and passing through Samaria. It was mainly in the summer that the journey between Jerusalem and Galilee did not pass through the sweltering Jordan Valley but through hostile Samaria.

A feast in Jerusalem. The unnamed feast in Jerusalem in John 5:1, which Jesus attends alone, has no parallel in the other Gospels. The text in 5:33-35 suggests that John has already been arrested. - The starting point in Mark. In Mark, Jesus' mission only really begins in Galilee after John the Baptist has been arrested. There he gathers the twelve and they go around the villages and towns. The fish stories must be placed in the winter.

The 5,000 men. After a few months, John is beheaded. Five thousand men gather around Jesus. According to Mark 6:39, the grass is green, which fits with the statement in John 6:1 that it was almost Passover. According to John, they wanted to make Jesus "king." It seems that he, the successor of the beheaded John, has reason to fear for his life.

The turning point in Mark. Jesus withdraws to the north and stays outside Galilee as much as possible. The transformation on the mountain has no parallel in the Gospel of John, but there are Peter's words that he is the Messiah (Mark 9:29 and John 6:69). From here, Mark skips the necessary months until the final journey to Jerusalem, while Luke turns all the material into a long journey from the transformation to the crucifixion (Luke 9:51-19:41). - Travel between Galilee and Jerusalem in Luke. The geographical information in Luke points to multiple routes and thus also to multiple journeys between Galilee and Jerusalem:

- In Luke 9:52, Jesus travels through Samaria to Jerusalem and not through the Jordan Valley (which would be understandable because of the summer heat or because he did not want to be recognized). Verse 58 indicates that Jesus has no safe home.

- In Luke 10:38, Jesus is with Martha and Mary in Bethany near Jerusalem. Luke omits the place name.

- Luke 13:31-35 speaks of the danger Jesus faces in the territories of Herod Antipas (Galilee and the eastern Jordan Valley). Jesus seems to be saying goodbye to a city he has visited many times: "Jerusalem, Jerusalem, (...) How often I wanted to gather your children together as a hen gathers her chicks under her wings, but you were not willing. Your city will be left to its own devices. I assure you: you will not see me again until the time comes when you say, 'Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord!'"

- Luke 17:11 is curious: On his way to Jerusalem, Jesus travels through "Samaria and Galilee" instead of the Jordan Valley and Jericho. This only makes sense if he first has to go north, for example to pick up the women in Galilee (Luke 23:49). In 18:31-35, they accompany him on his last journey to Jerusalem before Easter. Now they are heading south through the Jordan Valley, past Jericho.

-

Travel between Galilee and Jerusalem in John. It is quite possible that the information in Luke is not arranged chronologically. Luke may simply have brought together a few separate travel stories. On the other hand, the journeys in John fit so well with the geographical information in Luke that one wonders whether there is not a shared historical reality underlying them:

-

In John 7, Jesus travels secretly to Jerusalem for the Feast of Tabernacles in early autumn. There, protected by the celebrating crowd, he reappears in public.

-

In winter (John 10:22), he is back in Jerusalem for Hanukkah.

-

After Hanukkah, he stays in the eastern Jordan Valley (10:40). At the request of Martha and Mary, he comes to Bethany because their brother Lazarus is ill (11:1). After the commotion (Jesus raises Lazarus from the dead, according to John), it is no longer safe for Jesus there.

-

Jesus goes into hiding in the desert town of Ephraim, in the north of Judea (11:53-54). At Passover (11:55), Jesus goes to Jerusalem for the last time with his disciples and the women (19:25). Jesus therefore had to go north first. Six days before the feast, they arrive in Bethany, which lies on the route as they travel south through the Jordan Valley.

-

-

This is the end of Mark's account. As in Mark and Matthew, the last part of Luke and John is devoted to Jesus' last week in Jerusalem.

The journeys between Galilee and Jerusalem in the Gospel according to John correspond to the geographical information in the Gospel according to Luke. John thus recounts what was already present in Luke but not highlighted by him: an exciting period in which Jesus was without a safe home and needed the protection of the masses during the festivals in Jerusalem in order to appear in public. When even that became too dangerous, he went into hiding, only to make his final journey with his followers from Galilee at Easter.

Add comment

Comments