The countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea, around the year 80

Introducing: Luke and Acts of the Apostles

Jesus had not returned.

Perhaps you need to let that sink in after reading Matthew: the temple had fallen and Jesus had not returned.

In a seven-year war, the greatest war of the first century, the Jewish people were humiliated and torn apart, countless numbers were murdered, driven into exile or enslaved, and Jerusalem was burned and destroyed. The God of Israel had abandoned his people. The rebels had been wrong and died like rats in a trap. The Jews were scarred by this for centuries. Rabbinical Judaism, without a king or high priest, was born out of the ruins of this war.

The followers of Jesus, most of them just as Jewish as their brothers and sisters, were also at a loss for words. They too had every reason to believe in a cosmic struggle between good and evil: the emperor who had burned Christians in Rome as torches would be defeated by God and his anointed one. Nero was dead, but the Romans had won the war and Jesus had not returned.

Was that the will of Almighty God, or does the Spirit of God work in a different way? On a deeper level?

Alexandria, Egypt's largest port, where grain was shipped to Rome. © Balage Balogh, Archaeology Illustrated.

A new Messiah in Alexandria?

There was a young priest, Joseph (in Rome they would call him Josephus), who had been sent by the rebels to Galilee to organize resistance against the approaching Roman army. General Vespasian and his son Titus arrived from Antioch with five legions and auxiliary troops: some 70,000 heavily armed, well-trained soldiers. Josephus lost without a chance but saved his own life when he greeted Vespasian: "Not the Jews, not Emperor Nero, but you are the new ruler of the world. You are the star that is rising in Israel and will shine upon the whole world."

Vespasian took Josephus into his service as an informant, translator, and spokesman. Later, when Vespasian became emperor, Josephus wrote a history of the Jewish War in seven books, first in Aramaic and then again in Greek. He wrote to please his lord, the emperor, and to defend his own role, both to his fellow countrymen and to the Romans.

Back to the year 68. The Roman Empire is in turmoil: in the east, the Jewish War is raging, and in the north, the Batavian Revolt is underway. In Gaul, the governor is calling for lower taxes and a new emperor, and from Spain, General Galba is marching on Rome. Nero commits suicide. In January 69, Galba is assassinated because the legions along the Rhine want a different emperor, General Vitellius. In Rome, they want Otho, but he is no match for Vitellius' troops and commits suicide after three months. In Syria, Judea, and Egypt, the legions proclaim Vespasian emperor. He leaves the siege of Jerusalem to his son Titus and marches to Alexandria in Egypt, where Rome's grain comes from.

The atmosphere is jubilant, messianic. A few decades later, the Roman historian Tacitus describes in his Histories IV.81 how even the practical Vespasian comes to believe in his divine calling:

During the months that Vespasian waited in Alexandria for the regular summer winds and calm seas, numerous miraculous phenomena occurred that pointed to heavenly favor and a certain sympathy of the gods toward Vespasian.

A man from the lower classes in Alexandria, known for his wasted eyes, fell to his knees before him, groaning and begging for a remedy for his blindness, on the instructions of the god Serapis (who, due to the superstitions of the Egyptians, is more revered than the rest). He begged the emperor to have the kindness to cover his cheeks and eye sockets with some saliva. Another man with a lame hand prayed to him, on the prompting of the same god, that the emperor's foot, the sole of his foot, would step on that hand.

Vespasian's initial reaction was mocking, and he dismissed them. When both persisted, he was afraid of appearing gullible, but at the same time he cherished hope because of their requests and the words of flatterers. Finally, he asked doctors to assess whether such blindness or paralysis could be remedied by human intervention.

Their analyses differed. In one man, his eyesight was not completely impaired and would return if the obstacles were removed; in the other, the joints had become misaligned, which could be remedied by the application of healing powers. Yes, perhaps the gods so desired, and the emperor had been chosen for this divine task. And finally, a successful cure would make Caesar famous, while failure would only make the unfortunate men look ridiculous.

Well, for his luck, everything is within reach, thinks Vespasian, nothing is too crazy, and with a happy face, under the tense interest of the crowd of bystanders, he does what is asked. Immediately, the hand was usable and the blind man saw the light of day again. Both are now confirmed by eyewitnesses, now that the reward for lies has been removed.

On December 20, Vitellius was assassinated, and on December 21, the Senate recognized Vespasian as emperor while he was still in Alexandria. A new dynasty was born. Vespasian ruled for ten years and was succeeded by his popular son Titus, who ruled for two years. He was followed by his younger brother Domitian, who would be emperor for fifteen years, until the year 96. Meanwhile, according to Tacitus, the struggle continued in Judea, despite omens in the sky and around the temple that the gods had abandoned it:

All this alarmed few. Most were firmly convinced that their ancient priestly writings contained a prophecy: at that very time, the Orient would grow strong, starting in Judea, and then become master of the world. Vespasian and Titus had been foretold in that oracular language, but the people had such a grand destiny in mind for themselves, the normal human eagerness, that even setbacks did not make them see the truth.

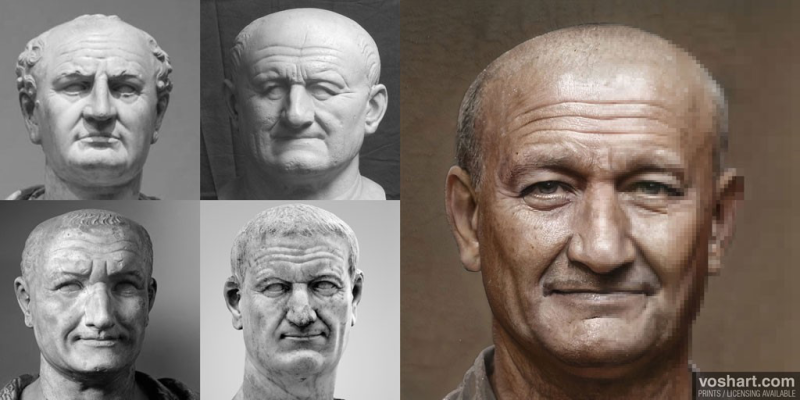

Vespasian, emperor from 69 to 79, died at the age of 69. His face was reconstructed by © Daniel Voshart.

Titus began the siege of Jerusalem a few days before Easter with four legions. The city is too strong for a direct attack, but it is overflowing with pilgrims and refugees who will consume it from within. Titus surrounds Jerusalem with a high wall. Josephus must address the inhabitants and undermine their confidence in God's intervention.

Luke describes how Jesus must have foreseen all this:

How Jesus drew nearer with his eyes fixed on the city and wept over it!

"If only you had understood today what would bring you peace," he says, "and what is now hidden from your eyes: For days will come upon you when your enemies will build a rampart around you, surround you, and press in on you from every side. They will burn you to the ground, along with your children within you. They will not leave one stone upon another in you, because you did not recognize the time of your visitation.”

We read about it in Josephus and Tacitus. Absolute horror. Hundreds of thousands dead, hundreds of thousands of refugees. Another hundred thousand prisoners who were taken to Rome as slaves, forced laborers, and lion fodder. To the end-time sermon in Mark and Matthew, in which Jesus begs people to flee in time, Luke adds how it happened:

“When you see Jerusalem surrounded by army camps, know that its destruction is near. Are you in Judea? Flee to the mountains!

Are you in the city? Get out! Are you in the countryside? Don't go into the city. (...)

They will fall by the edge of the sword; they will be led away captive among all nations; and Jerusalem will be trampled by the Gentiles, until the times of the Gentiles are fulfilled."

Titus, emperor from 79 to 81, died at the age of 41. Reconstruction by © Daniel Voshart.

It is said that many followers of Jesus did indeed flee. Like so many Jews, many will have found their way to Jewish communities around the Mediterranean. They would have been taken in by the communities of Jesus' followers in cities such as Rome, Corinth, and Ephesus. Were they able to process their traumas and disappointments? Did they take the Gospel according to Matthew with them? Did they share their views on Jewish law, their memories of Jesus and the apostles? How did they talk about the conflicts between James, Peter, and Paul? Did they hold Paul responsible for the conflict in Jerusalem and the stoning of James? How much authority did they have among the mixed congregations of Jews and non-Jews who wanted to follow Jesus of Nazareth? How did their arrival influence the writing of Luke's Gospel and the Acts of the Apostles?

Luke

"Greetings from Luke, the beloved physician," Paul writes to the church in Colossae. And it seems that he is referring to someone who is not circumcised. A pagan, therefore, a God-fearing pagan who believed in the God of Israel, the one God. In his letter to Philemon, a member of that church, he calls Lucas his "fellow worker," along with Mark and two other men. Paul is still awaiting his first trial in Rome.

A few years later, when he is imprisoned in Rome again, he writes to Timothy: "Only Luke is with me; bring Mark with you when you come, for he is very useful to me in my work." Some Church Fathers saw this as a project by Paul and Luke to write Paul's gospel. But even if that were the case, it would not have been completed until after the Jewish War, years after Paul's death. Luke is said to have died in Boeotia or Bithynia in Asia Minor.

The author introduces himself

The author of the Gospel according to Luke, as we call it, published it without mentioning his name. But that does not mean that he does not appear in the text. Just as Josephus would do in his Jewish War, the author begins the Gospel with a preface, in which he explains why he is publishing his own account when accounts by others are already available:

“Since many have undertaken to compile a narrative of the things that have been fulfilled among us, just as they were handed down to us by those who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and servants of the word, it seemed good to me also, having followed all things closely, – to write an orderly account for you, most excellent Theophilus, so that you may be certain of the things you have been taught.”

With such a preface (which he repeats at the beginning of the book of Acts), the writer, with his character and personal experience, becomes part of the story. Whether this is objectively correct remains to be seen (even a novel can have such a preface), but the reader is invited to accept the story as reliable and true. In any case, the story is remarkably accurate in its depiction of the geography and rulers of numerous places. In an ancient manuscript of the book of Acts, which is somewhat more extensive than the standard version, the mixed community of Jews and God-fearing Gentiles in Antioch is described in the first person plural. Hence the idea that the writer may have come from that city.

This "we" figure will reappear on three more journeys. First in Troas, from where Paul crosses over to the city of Philippi in Macedonia (late 40s). Then during the long journey in the mid-50s to raise money in Macedonia, Achaia, and Asia and bring it to Jerusalem. Finally, we see him again a few years later when Paul is transported to Rome. Yes, he even describes the terrifying shipwreck in the first person plural. The writer is therefore not someone who was present everywhere, but someone who spoke to many people, was a good observer, could organize his information, and could describe all this in a comprehensive work.

In short, the physician Luke is an excellent choice for those who believe that the presented author is also the real author. He would then be the only non-Jewish author in the New Testament. In any case, you can read the work well from his perspective: a reliable narrative history of Jesus and the mission among the nations. The work is intended to reassure people like Theophilus around the year 80 of the first century, some 15 years after Paul's death and about 10 years after the fall of Jerusalem. It was written at a time when followers of Jesus from Palestine were spreading their own stories, beliefs, and customs throughout the communities around the Mediterranean.

That does not mean that Luke is an unbiased historian. Even the renowned Tacitus was not: as a senator, he was pro-Rome and republican (i.e., opposed to the empire). Josephus was pro-Jewish but also loyal to his patron, Emperor Vespasian, and his son Titus. So it does not mean that things happened or were said exactly as Luke describes them. The first two chapters even resemble a Bollywood film in which people repeatedly burst into song. Luke selects, systematizes, and stylizes his material to make his point as convincing as possible. He even deliberately introduces variations in the descriptions of the ascension and the conversion of Paul that are visible to everyone. He finds this more beautiful or meaningful. However, this does not mean that Luke was free to invent miracles he did not believe in himself. Josephus and Tacitus also believed in miracles. In fact, part of Luke's audience consisted of people who had experienced parts of the story themselves. To convince them, he had to remain credible.

Why would Luke write at all?

There is much debate among theologians about the purpose of the Gospel and the Acts. And why does it actually end with Paul's arrival in Rome, just before the trial and persecutions under Nero begin? The answer to these questions depends, of course, largely on the time in which this work was written. In this book, I always start with how the text presents itself, and here it is presented as a two-part work by a traveling companion of Paul. But you could also think of it as two separate works from a later date that together or separately are intended to give that impression. Both interpretations have enough support among theologians to be taken seriously, but for our story we will assume the first.

If you read these books as a two-part work by a traveling companion of Paul, there are still at least five ways in which you can ask yourself why "Luke" wrote them. In the prefaces to the Gospel and the Acts, you can read what he himself gives as his reason. You can deduce what he considered important from the introduction, structure, and conclusion of his work. You can also examine what he does differently from Mark and Matthew. You can compare his travelogue and theology with Paul's letters. And you can think about what he should do in his situation. The point is to read in a way that does justice to all five perspectives.

One thing is clear: Luke is on the defensive. He defends the gospel, the mission among the nations, Paul, and, of course, himself as a member of that movement. On top of that, he has to convince Paul's followers to compromise. And he does so in a breathtaking work: he describes the gospel and the mission among the nations as the ongoing work of salvation of the Spirit. He sees a line in the history of incarnation and inspiration. And he sees a way out for Jews and non-Jews in the churches, based on listening to the Spirit of Jesus. Not to the Spirit that was once in Jesus of Nazareth, but to Jesus who, through the Holy Spirit, still leads his followers today.

The structure of the Gospel and Acts

With his two-part work, Luke provides more than a quarter of the New Testament; it takes four to five hours to listen to it all. His work has influenced us enormously. Just as Mark shaped our view of Jesus' suffering and Matthew shaped our view of his teaching, Luke shapes our view of Paul and the church. His work has also shaped the holidays and the church year: Not only at Easter, but also at Advent, Christmas, Ascension, and Pentecost, we experience the story of Jesus and the apostles as Luke wrote it down.

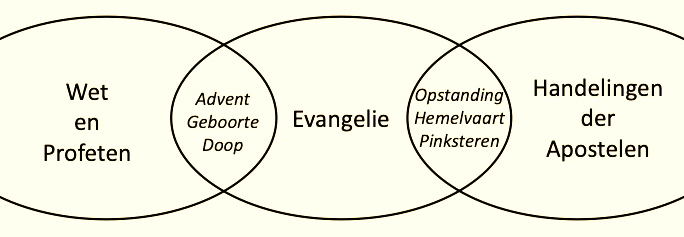

For Luke, the history of salvation can be divided into three parts:

- First, God gave the Law and the Prophets, who spoke through the inspiration of the Holy Spirit. This period ends with John (according to Luke 16:6).

Transition: Then there is a transition period full of angels in which heaven and earth touch each other. Jesus is conceived and baptized in the Holy Spirit. He is then tempted by the devil for 40 days in the desert and served by angels. As a narrator, Luke expresses this by writing the birth stories in the style of the birth stories in Genesis and I Samuel, and by announcing the arrival of John as an Old Testament prophet with the year and the reign of the rulers when he arises. This raises a question for me as a reader: Would Luke deliberately describe this transition period in a more biblical and symbolic way because he finds the "historical" language less suitable here?

- Then Jesus, who, like his predecessors Joshua and David, is about 30 years old, begins in Nazareth with Isaiah's prophecy: "The Spirit of the Lord is upon me to preach the Gospel to the poor." This marks the beginning of the "year of the Lord's favor" and the kingdom of God that John could only dream of (7:28). Jesus inaugurates the kingdom of God with miracles and signs. He embodies God's Spirit.

Transition: With his resurrection, a new period of transition begins in which angels speak. The risen Jesus reveals himself to his disciples for 40 days and ascends to heaven to pour out the Holy Spirit on his followers from there, at the right hand of God (Acts 2:33).

- This marks the beginning of the time that the prophet Joel announced to Peter: "In the last days, I will pour out my Spirit." And the proclamation of the gospel begins that day with Jews and converts from all nations. Through the Holy Spirit, Jesus inspires and guides his apostles. They speak in tongues, see visions, and heal people.

You can see how the Gospel and the Acts are structured in a somewhat similar way. The transitional periods are similar, as is the beginning of the preaching. This also applies to the motif of the journey: in the Gospel according to Mark, the transfiguration on the mountain is the turning point after which Jesus sets out on his journey to his death in Jerusalem. Luke even reinforces this somewhat: on the mountain, it becomes clear that Jesus will have his "exodus" in Jerusalem, and from that moment on, it is one long journey to Easter. Even though Luke uses material that points to multiple trips back and forth (as in the Gospel according to John), he still saves Jerusalem for last. It is no different in the Acts. Everything revolves around the meeting of the apostles in chapter 15 on the question of whether Gentiles can be saved as non-Jews or whether they must first convert to Judaism. Three times (15:20, 15:29, and 21:25) these four minimum requirements for non-Jews not to defile a community of kosher Jews are listed: "abstain from things sacrificed to idols, from blood, from things strangled, and from sexual immorality." Once that is clear, Luke simply follows Paul on his travels until he finally arrives in Rome, even though he uses material that shows that the problem had not yet been resolved and that the gospel had already arrived in Rome earlier.

Could it be that Theophilus heard the gospel from Paul himself in those years, or that he was Lida from one of the churches that Paul had inspired with his letters and emissaries?

Comparison with Mark and Matthew

Like Matthew, Luke uses the Gospel according to Mark as the backbone for his narrative, interspersed with sayings of Jesus (largely the same ones used by Matthew). And like Matthew, he precedes this with a pregnancy by the Holy Spirit and a genealogy. Luke also concludes with resurrection experiences and a farewell scene. Like Matthew, he sometimes improves Marcus's "Aramaic" Greek. However, there is also quite a bit of material that only Matthew uses, or only Luke. Think, for example, of the parable of the prodigal son, or Herod Antipas' involvement in Jesus' condemnation. And Luke's own material is also old: it shows the necessary Aramaic influences that we do not see when Luke himself is speaking.

Wikipedia Creative Commons: Original: Alecmconroy Derivative work: Popadius - derived from: Relationship between synoptic gospels.png: The relationships between the three synoptic gospels. Source: Honoré, A.M. (1968). "A statistical study of the synoptic problem". Novum Testamentum 10 (2/3): 95–147.

Many believe that Luke wrote independently of Matthew. But could it be a coincidence that Luke uses the same formula as Matthew? Is it not possible that he read or heard Matthew himself? What best explains the similarities and what explains the differences? We have already seen that Luke rephrases the predictions about the end times in light of the events after the fall of Jerusalem. In addition, he also has different birth stories and a different genealogy (all the way back to Adam). He does not follow Matthew in regrouping Jesus' sayings and sometimes seems to quote them more freely. He follows Mark's storyline more closely but omits a few passages—or uses a shorter version. Was that because he did not have the Gospel according to Matthew at his disposal when he wrote? Or did he see Matthew's birth stories as a kind of artistic license? Or was it that his already lengthy work would become too full and confusing with those stories included?

We also learn something about Jesus' sayings: Luke seems to take much more liberty with the conversations and speeches of Peter and Paul (as was customary among ancient historians) than with Jesus. Like Matthew, Luke works with an authoritative collection of sayings from which he cannot or does not want to deviate too much.

When you compare the three Gospels, you first notice that they are very similar, suggesting that there were already fairly reliable traditions of Jesus' words and deeds, exactly as Luke writes in his prologue to Theophilus. In addition, Luke is able to subtly emphasize the work of the Holy Spirit and the future mission among the nations, which he will elaborate on in the Acts. Finally, by publishing a two-part work with a similar structure, he can show that the mission among the nations stems from the same gospel of Jesus and that one Holy Spirit drives both stories.

Comparison with Paul

Anyone who compares the Acts with Paul's letters as discussed in this book will notice two things. First, there is a considerable similarity in Paul's itinerary, although Luke simplifies it here and there (as he also does with Jesus' journeys to Jerusalem). But there is also a huge difference: the letters focus on the great conflict between the apostles over the Gentiles and the observance of the law, but in the Acts there is good cooperation and harmony between James, Peter, and Paul. Some theologians find this difference so great that they cannot believe that Luke was a traveling companion of Paul. Others even think that he did not know the letters. But that does not fit with his good knowledge of Paul's travels. Moreover, we know that the letters to the Galatians, Corinthians, and Romans were in circulation early on. Let us therefore assume that Luke deliberately deviated from Paul.

Compare his account with the letter to the Galatians. They each have their own rhetoric, and you have to think about why they write the way they do for each point:

- Luke is silent about the major conflict between Peter and Paul in Antioch, while Paul devotes an entire letter to it.

- Paul says that only he and Barnabas are apostles to the Gentiles, but Luke says that God had chosen Peter first for this task and that Paul always began in the synagogue before turning to the Gentiles.

- Luke reports that Paul had to deliver a letter from Jerusalem to the Gentiles concerning, among other things, the eating of sacrificial meat, while Paul says that they should not forget "the poor."

- Paul emphasizes that he did not have to circumcise Titus, but Luke says that Paul decided on his own initiative to circumcise Timothy because he had a Jewish mother.

- Paul tries to create as much distance and time as possible (as much as seventeen years, if you do not read his rhetoric critically) between himself and the apostles because he disagrees with them and does not want to accept their authority over him and "his" churches. Luke, on the other hand, emphasizes the agreement between Paul, Peter, and James in order to show that the mission among the nations was supported by all the apostles from the beginning.

It is quite possible that many Jewish followers of Jesus in Israel had long heard of the letter to the Galatians and that they condemned Paul for his criticism of the law, circumcision, and angels, and for his disparaging remarks about the apostles and James's messengers. After all, Paul wrote more sharply than he spoke (see also 2 Corinthians 10:10). Perhaps that is why Luke does not portray Paul as the controversial letter writer but as the tireless traveler for the Gospel. Luke needs to make Paul acceptable to them, and three times he recounts how Jesus himself called and changed Paul. In fact, when Paul reports to James in Jerusalem, Luke has James mention the accusations that Paul was teaching the Jews among the Gentiles not to keep the Law of Moses and not to have their children circumcised. James then assumes that this accusation is unjustified. He suggests that Paul demonstrate his observance of the Law to all people, and Paul agrees without hesitation. If the letter to the Philippians indeed refers to the testimony of Jewish followers of Jesus against Paul in Rome, then it fits Luke's purpose to end his story just before that trial.

What would Lucas have wanted to achieve?

When we look at the big picture, the writing of Luke's Gospel and the Acts of the Apostles fits perfectly around the year 80, when Jewish believers from Israel joined the mixed congregations around the Mediterranean. They brought with them their doubts about this "second-rate apostle" and his mission among the nations. Their authority made people like Theophilus uncertain: "Is what I learned from Paul correct? Was he really trustworthy?"

The core of the accusation is expressed in Acts 21:18-25:

The next day Paul went with us to James, and all the elders were present. After greeting them, Paul reported the things God had done among the Gentiles through his preaching. When they heard this, they praised God and said,

"You can see, brother, that many thousands of Jews have accepted the faith, and all of them are living in accordance with the law.

Now they have been told that you are teaching the Jews who live among the Gentiles to abandon Moses, telling them that they do not need to have their children circumcised or to keep the other requirements of the law.

How can we refute this? They will undoubtedly hear of your arrival. Therefore, do as we tell you. There are four men among us who have made a vow. Take them with you, purify yourself with them, and pay the cost of their sacrifices, so that they may have their heads shaved. Then everyone will see that the stories told about you are untrue, and that you yourself observe the law.

As for the Gentiles who have accepted the faith, we have written to them, informing them of our decision that they must abstain from meat sacrificed to idols, from blood, from meat containing blood, and from sexual immorality.

To prevent the impending schism, Luke writes his life's work. He shows the churches of Asia Minor, Macedonia, and Achaia that their gospel is the same gospel and that the mission among the nations goes back to Peter in Acts 10. The Holy Spirit himself shows him in a vision that he may eat unclean food and associate with Gentiles when God accepts them. In his writing, Luke restores the compromise that he has James express in Acts 15: the Gentiles are saved as Gentiles, and the Jews remain faithful to the Law of Moses. In order to interact with Jews in a kosher manner, the Gentiles must adhere to four minimum requirements: no meat from animals sacrificed to idols, no blood, no animals that have been strangled, and no sexual immorality. This position is still necessary in the 1980s to maintain harmony, but will disappear within a few decades in a movement that increasingly consists of non-Jews. But for the time being, Luke first makes Paul less offensive to Jewish believers so that they can read him with different eyes. He comforts them in their disappointment that the Lord has not yet returned. And he offers them a new perspective: look at what has happened from above. See the Spirit blowing over the earth.

Holy Spirit

The word "spirit" in the New Testament is not used in its Greek sense. In the Aramaic world, this term describes numerous infections, viruses, and mental disorders. The early Gospel according to Mark therefore refers to unclean spirits 15 times and only 5 times to the Holy Spirit of God. In Matthew, it is the other way around: he mentions the Holy Spirit twelve times. Luke goes even further: in the Gospel, he mentions the Holy Spirit seventeen times and in the Acts of the Apostles fifty-six times. There, the Spirit speaks to and in the believers and pours itself out upon them. The Spirit reveals itself in dreams and gives insight. The Spirit drives them to action or holds them back.

In fact, the Spirit is Jesus. In the Law and the Prophets, it is the Spirit of God who inspires the prophets (the word Spirit is feminine in Hebrew and neuter in Greek), but in the Gospel, the Spirit has become "flesh and blood" in Jesus. Luke shows this to the reader when the heavily pregnant Elizabeth greets the pregnant Mary. Elizabeth speaks filled with the Spirit of the Lord, but Mary is the mother of the Lord himself. And after Pentecost, Jesus pours out the Spirit. In this way, he still speaks and heals through the Spirit. Through the Spirit, Jesus reveals himself to Paul. He has become "the life-giving spirit" (1 Cor 15:45), so that Paul and Luke no longer distinguish between God's Spirit and the Spirit of Christ (Rom 8:9, Acts 16:7). Jesus has become the personification of God. This is also beautifully illustrated in the death scenes. On the cross, Jesus cries out, "Father, into your hands I commit my spirit," and after Pentecost, Stephen cries out, "Lord Jesus, receive my spirit."

Anyone who pays attention when reading Acts 8-15 will see that Luke portrays the Holy Spirit as the driving force that leads the apostles step by step to bring the gospel to the Samaritans and the Gentiles as well. Peter's dream is particularly crucial: the Holy Spirit can declare kosher what the Jews had previously considered unclean. It is the Holy Spirit who fills Peter's non-Jewish listeners and thus declares them clean. The Holy Spirit sends Barnabas and Paul to the nations, and the Holy Spirit leads Peter and James to the conclusion that non-Jewish believers are saved without first converting to Judaism and the law of Moses.

Summary: Driven by the Spirit, around the year 80.

In the year 70, the Romans destroyed Jerusalem and the temple of God, and the Lord did not intervene. Jesus had not returned. Hundreds of thousands of Jews died in this war. Hundreds of thousands also fled the violence of war or were taken away as slaves by the Romans. The victorious Vespasian became the new emperor of Rome and had the Colosseum built with the proceeds from the plunder. Many followers of Jesus from Israel will have joined the community around the Mediterranean. And so the old debate between the now deceased Paul and James flares up again: how can Jews and non-Jews form a community together? And how should Paul's followers respond to this? The answer is found in an anonymous diptych that makes up a quarter of the New Testament.

- With the Gospel of Luke, the author shows that his foundation is the same gospel that Mark and Matthew describe, although the author remains faithful to Mark's storyline but also adds his own material. He uses the same source of sayings as Matthew but spreads them more throughout the story. However, Luke's Gospel was clearly written after the fall of Jerusalem: instead of Matthew's "immediately," we read that the Romans will rule for "times" before the Lord returns.

- To investigate why this was written, you can compare the Acts of the Apostles with the letter to the Galatians. Where Paul presents himself as the apostle (missionary) of the nations, the writer emphasizes that this already began with Peter. While Paul emphasizes that the Greek Titus did not need to be circumcised, the writer tells us that Paul circumcised the Jewish Timothy with his own hands. Where Paul considers circumcision unnecessary even for Jews, the writer presents a compromise to both the law-abiding Jews and the non-Jews: they can form a community as long as they do not commit sexual immorality and do not eat meat that comes from sacrifices to idols. Where apostles clash, the writer emphasizes the role of the Holy Spirit who drives all apostles forward.

The author presents himself as someone who experienced part of the second story himself and who, for the first story, made careful inquiries with the people who were there at the beginning, whom he calls the "people of Weg." Many references to places and administrators are surprisingly detailed and accurate. Readers are quickly reminded of Luke, a doctor from Antioch. He is said to have died in Boeotia or Bithynia in Asia Minor. A traveling follower of the apostles who never met Jesus himself. It must have been someone like that to be able to write this.

Traveling at sea. © Balage Balogh, Archaeology Illustrated.

A bit of background information: Luke and the politicians

Many people don't know this, but all the dates relating to Jesus and Paul that you read in history books or on Wikipedia are based on the Gospel according to Luke. The other parts of the New Testament are simply not precise enough to arrive at a date. See here for an overview.

Of all the writers in the New Testament, only Luke is consistently interested in politicians and the areas they governed. They were also known to his audience in the first century from other sources. Many left coins and inscriptions behind and were mentioned in histories. Luke's readers could thus place the stories about Jesus and the apostles in the framework of their own history.

A solid setting does not necessarily mean that Luke's stories about Jesus and Paul are historically and chronologically reliable. Most historians, based on Matthew, assume that Jesus was born during the reign of Herod the Great, king of all Israel.

Lucas would then have made a mistake by linking this to the census of the year 6 under Governor Quirinius. But is that correct? Matthew was an artist, as we saw in the previous chapter. It is fitting for Matthew to symbolically place the birth of Jesus under "Pharaoh" Herod. With his reference to Herod, Luke may also be referring to his successor Archelaus, who ruled over Judea alone as "Herod the Ethnarch" (as he is called on his coins). Archelaus' journey to Emperor Augustus in Rome seems to lie behind the parable of the king in Luke 19:11-27. Luke also knows that Quirinius' census coincided with the revolt of Judas the Galilean (Acts 5:37), when the Ethnarch was deposed and Judea became a Roman province. A (great) grandson of Judas played an important role in the outbreak of the Jewish War in the year 66, undoubtedly known to Luke and a significant part of his audience.

If we read Luke and Acts without the Gospel according to Matthew, if we only ask ourselves what chronology Luke himself used, then we must start from what he himself wrote: according to Luke, Jesus was born under Quirinius (the year 6) and began his ministry under Pilate when he was about 30 years old. The book of Acts then begins around or in the year 36.